Chapter II.

DISTRIBUTION

DISTRIBUTION, as applied to tone, means the satisfactory “placing” of the dark and light tones that are used in the making of a pattern or picture. It is probable that the sense of fitness in our ideas of distribution depends on natural laws, on our knowledge of the average happenings in daily life, and particularly belongs to the sense of balance or equilibrium.

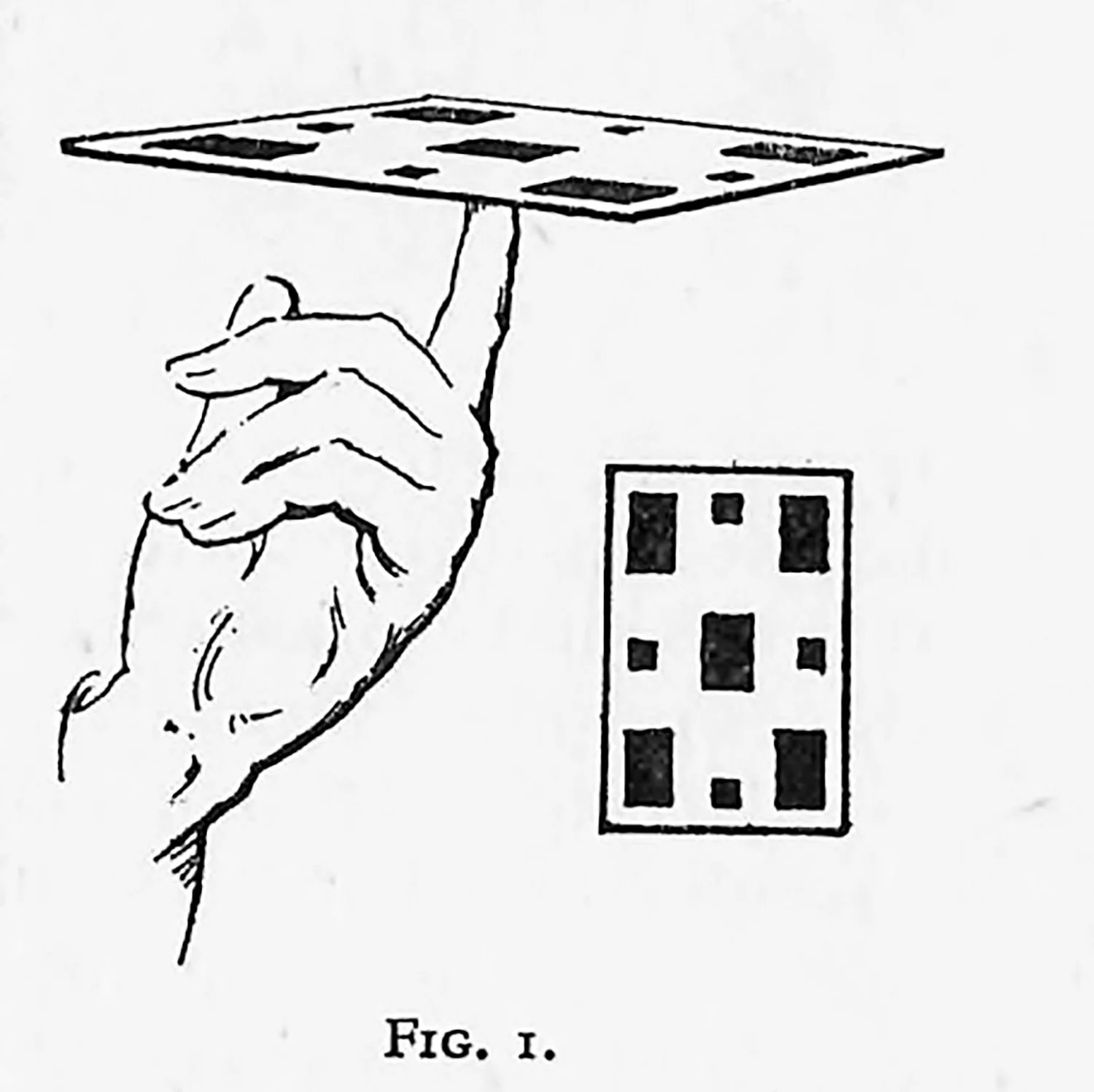

If a card be balanced on the tip of the forefinger, and pieces of lead of varying or equal sizes placed on it, it is possible to arrange them so that the equilibrium is maintained. An arrangement such as that illustrated in Fig. 1, with one central weight and four others equally disposed towards the corners, would preserve equilibrium. An infinite number of such regularly disposed arrangements are possible, and such an idea, although crude, gives us some idea of the basis of distribution in formal pattern.

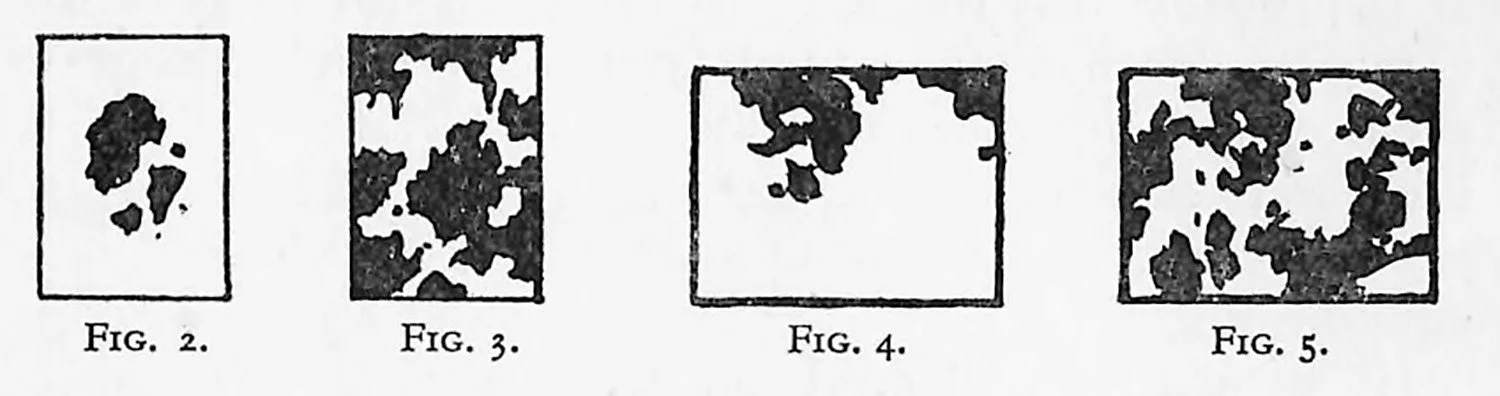

If pictorial distribution is to be understood, the idea of equilibrium must be extended, and a distribution giving equilibrium of an informal character must be employed. If the card be balanced as before, and a piece of lead placed just off the centre, equilibrium can be established by placing a few smaller pieces at a position on the side of the centre that is opposite. Such an atrangement is illustrated in Fig. 2, and it should be evident, without making the actual experiment, that equilibrium is again established.

It should be noted that as the pieces are removed to a greater distance from the centre of the card—towards the edges—it is still possible to establish equilibrium. Fig. 3 is an example of such an arrangement. Fig. 4 is an example of imperfect equilibrium. Fig. 5 is an example of a possible readjustment.

It follows that if a large piece approaches the edge, more pieces will be required to effect the balance, and a general spread-out arrangement results. Conversely, if a large piece be placed near the centre, less distribution is necessary. Seeing that this kind of balance is informal, it should follow that the shapes or pieces themselves should be unequal in area.

A rectangle containing equality of area in shapes with an irregular distribution is illogical, and consequently does not succeed in composition. Sometimes a decoration or composition is of necessity subordinated to its environment. A cathedral full of regularly disposed areas demands formality in the arrangement of its stained glass, and consistency frequently demands that an altar picture or decoration should become formal enough to agree with its surroundings, in which case distribution and areas become mote regular.

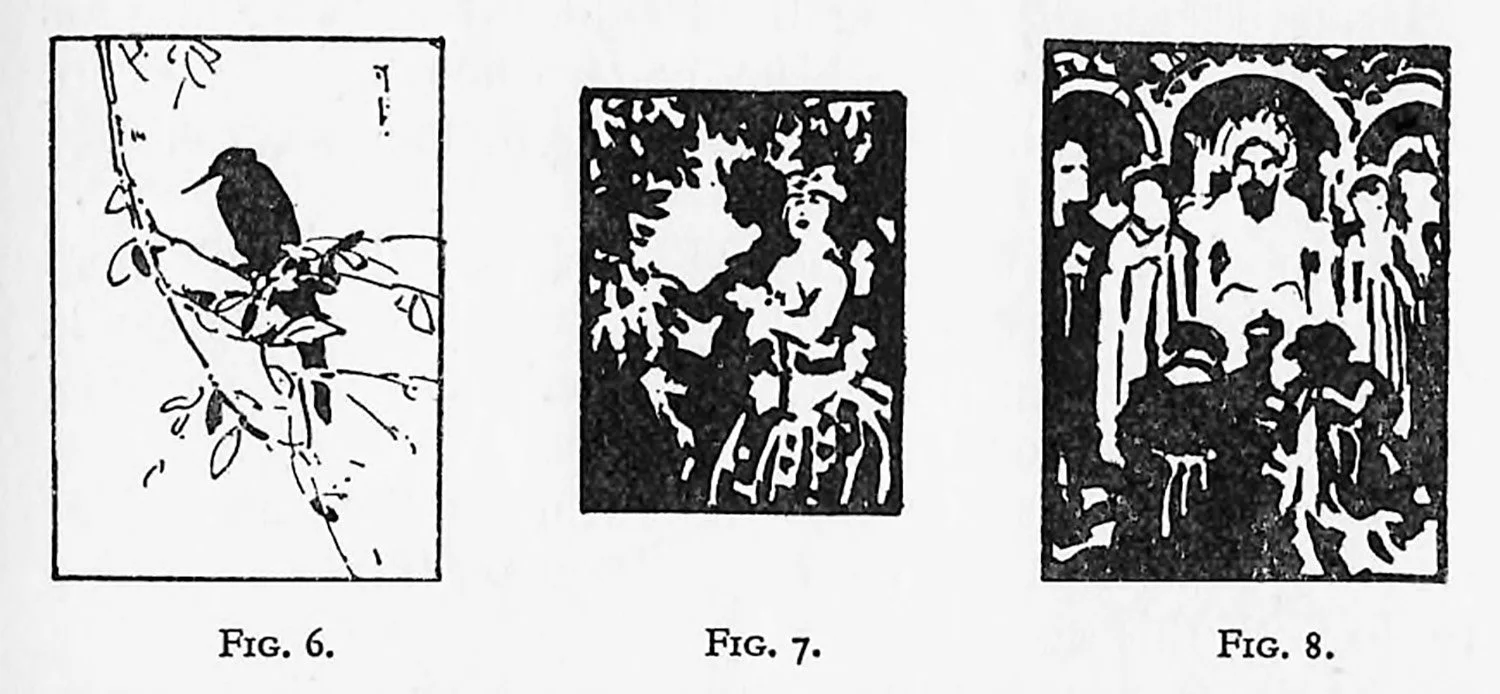

Three illustrations ate given in which the distributed tones possess recognizable forms. Fig. 6 is an example of the distribution that is arranged neat the centre. Many examples of this kind ate to be found in Japanese prints and other Oriental work. Fig. 7 is an example of the more open distribution, the darks spreading to the edges of the rectangle. Fig. 8 is an example of a more formal composition of the kind mentioned above. Here, then, we have the primitive beginning of distribution, and, whatever subtleties may follow, the sense of equilibrium should be maintained.

This sense of balance is inherent in everyone, for children delight in painting patterns of this kind until their attention is diverted—usually by their teachers—to the scientific tendering of isolated forms or objects. The pattern-sense rapidly retreats into the sub-conscious, and it is only by critical and patient study that the student can regain this sense of decoration. This, so far as tone is concerned, can be done by an intelligent appreciation of equilibrium in relation to distribution. What has been said of distribution of black on white will, of course, apply equally to white distribution on a black ground. The intermediate greys should also distribute themselves in a similar manner.

Although it is necessary that the areas or patches that are distributed in a given rectangle should have form or boundaries, yet distribution must, as far as possible, be conceived independently of form. This is said advisedly, for in most cases it is owing to the study of form, independently of pattern, that the sense of pattern becomes dormant. The sense of form is so ascendant in most students that it asserts itself like a malevolent spirit, and diverts the attention from distribution. To carry the sense of distribution further, experiments must be made in order ta see how far it is possible to displace our tones and yet recover the feeling of equilibrium.

If the surface of a rectangle be considered as covered with the intermediate grey, then the white and black might be separately distributed on this surface, making such patterns as (A) and (B) in Plate IV, which give a formal and informal distribution. This, however, is no more than would arise from the principles already stated, with the use of a third or intermediate tone.

If an intermediate tone be considered as covering the rectangle as before, and a black pattern be placed on it, out of equilibrium as in (C), (C) has a preponderance of black on the upper half.

Equilibrium can be established by placing the white tones with a preponderance in the same direction, as shown in (D). It can be seen that the introduction of white against this unbalanced black cancels the excess.

The well-known rule that the strongest light should be close to or against the strongest dark has little or nothing to do with this displacement.

The decorative or pattern requirement of our last experiment is to restore the lack of distribution, for it is in the management or organization of form that focus is usually given to a picture. It must be admitted, however, that the eye seems to pause at that portion of a picture in which the strongest contrast occurs.

This idea of displacement and its subsequent replacement holds good when mote tones are used. If the student examines a number of pictures with a view to the discovery of displacement, it will be found in varying degrees in all. Displacement adds a certain vitality by its apparently rebellious flying away from our accepted ideas of stability. It is the manner of the replacement that justifies its departure in the long run. Its practice makes for a more informal pattern because it covers up to some degree what might be termed simple distribution.

If the rectangle be covered with black or white (instead of the intermediate grey) it is possible to secure a satisfactory distribution by arranging a small piece of the extreme tone so that it balances a larger piece of the intermediate tone. A few examples of such balance are given in (E), (F) on the same plate.

Many other possible restorations or replacements will present themselves; for example, the white mount of a picture, if suitably cut, will to some extent correct a displaced distribution. Then, again, form can co-operate and replace imperfect distribution by drawing the attention away from the otherwise disturbing factor of unbalanced tone. Enough has been said, however, to enable the student to think out such matters for himself.