Chapter III.

INTERCHANGE

INTERCHANGE is a fascinating quality of light and dark. Its function is to give variety to simple distribution. It allows similar forms in opposite tones to be reiterated or repeated.

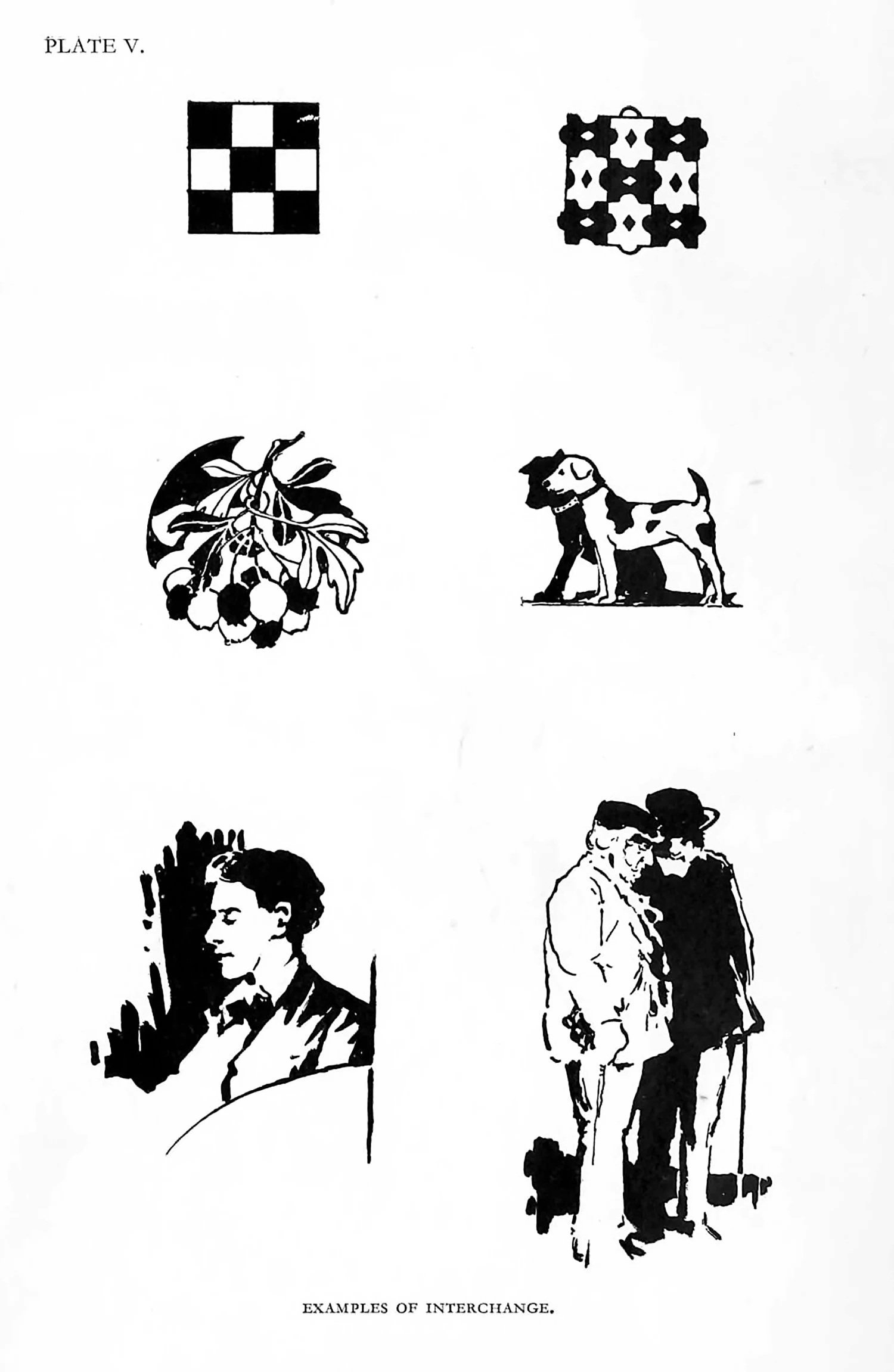

Interchange has been so fully discussed in most textbooks on formal design that a brief reference to it in ornament will be quite sufficient to allow its pictorial aspect to be examined. If we imagine a chess-board with its chequered squares alternately light and dark, and then on the light squares a shape of dark and on the dark squares a similar shape of light, the principle at once becomes manifest.

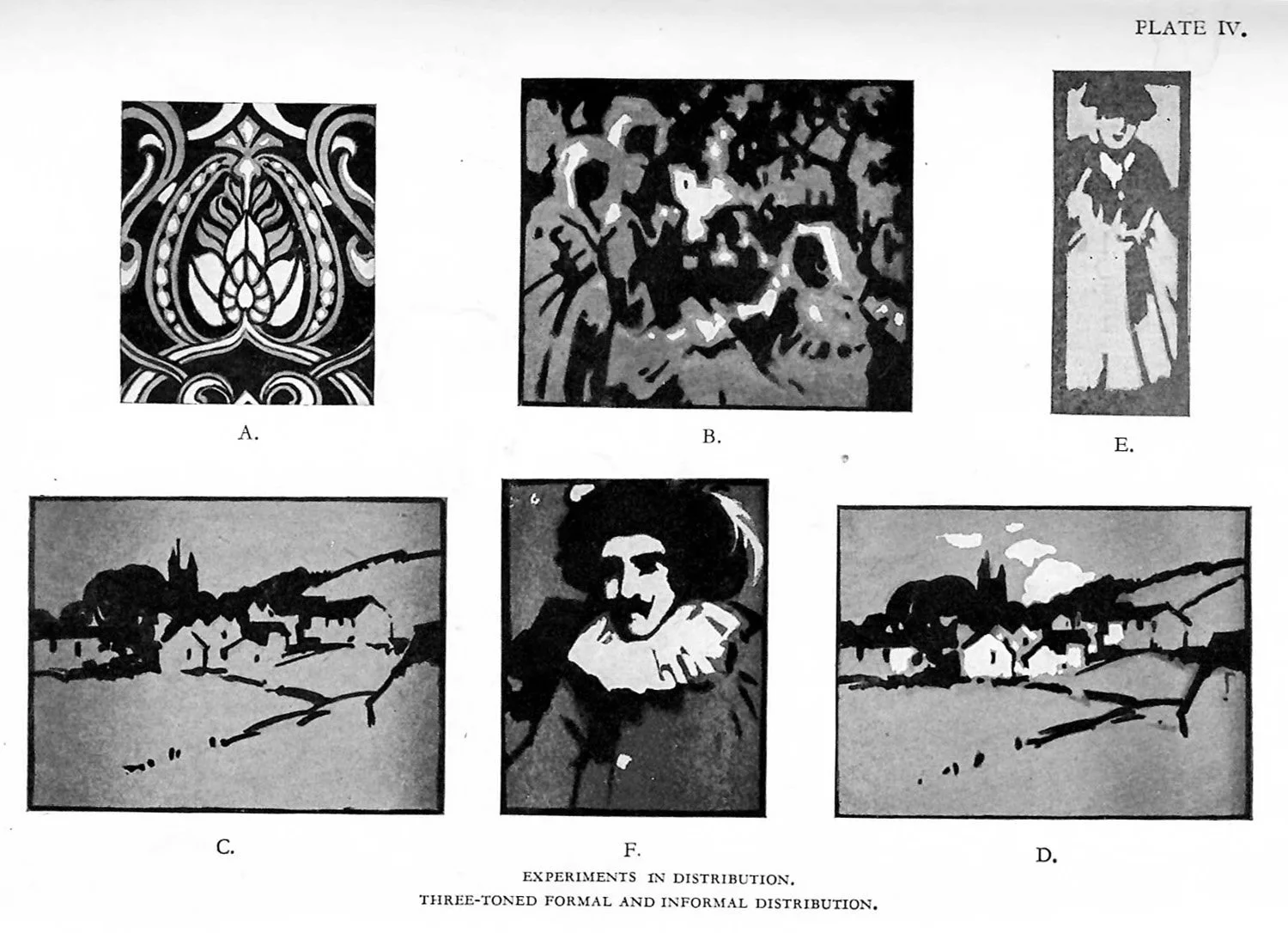

If we take the outlines of a couple of leaf-forms or animal-forms, arranging the tones so that one leaf is white with black veins and the other black with white veins—the animals to have white spots on a dark coat with a white background and black spots on the white coat with a black background—it will be seen that interchange provides a very ready means of introducing variety of tones with similar shapes. The illustrations given on Plate V demonstrate the principle from strictly formal designs to ornamental motives borderingon the pictorial.

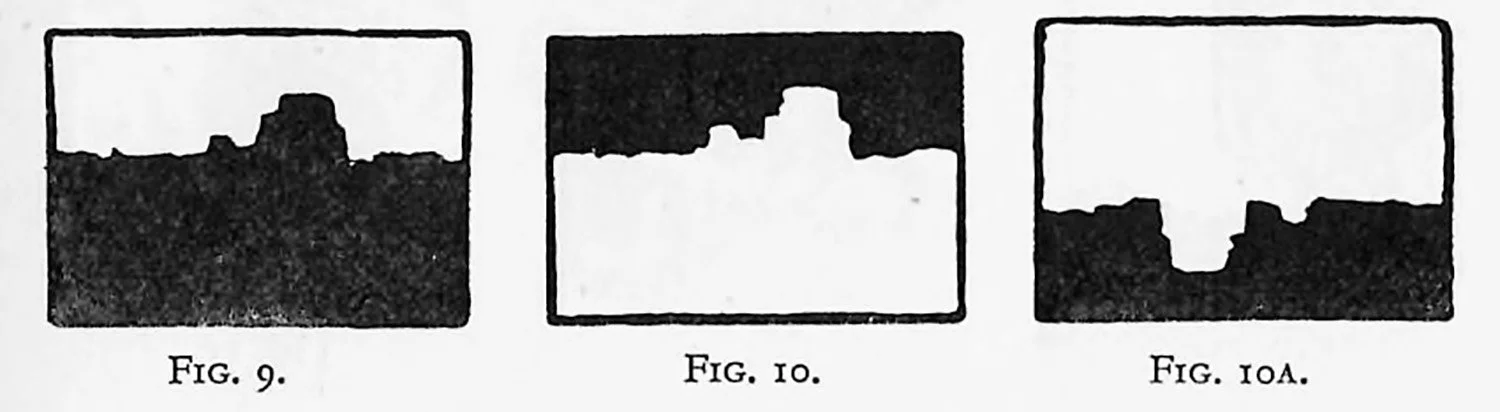

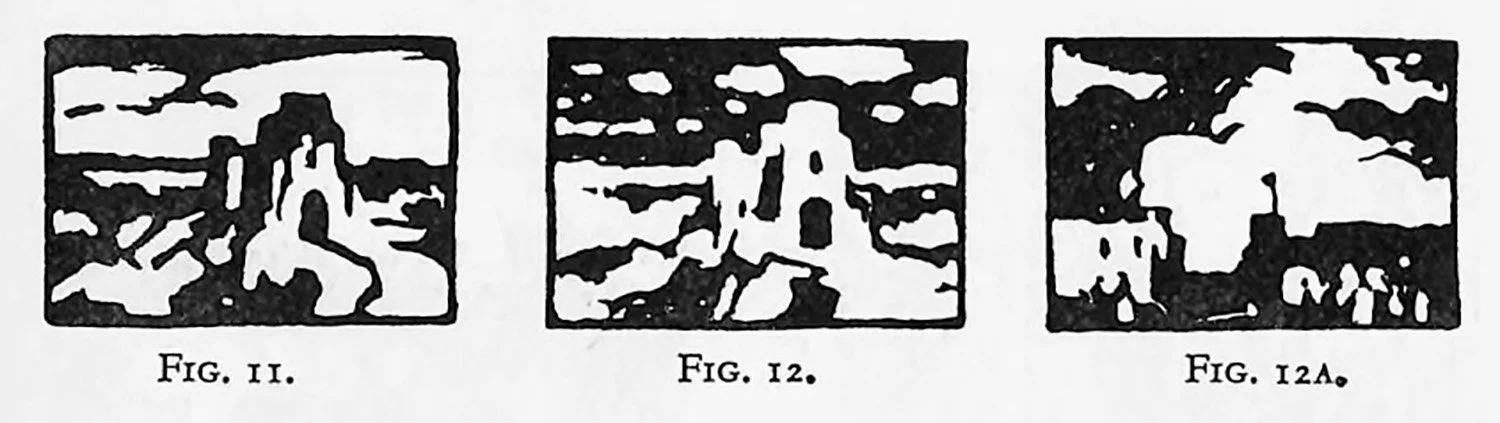

In pictorial work interchange is not quite so evident owing to the complexities of form, but it remains, nevertheless, a very active factor. In illustrations Figs. 9, 10 and I0A, a rectangle is shown with one portion dark and the other light, which, pictorially considered, might represent sky and earth. It is monotonous and lacking in distribution, but if some of the dark be transferred to the light area, and vice versa, the rectangle gains both variety and distribution, as in Figs. 11, 12 and 12a.

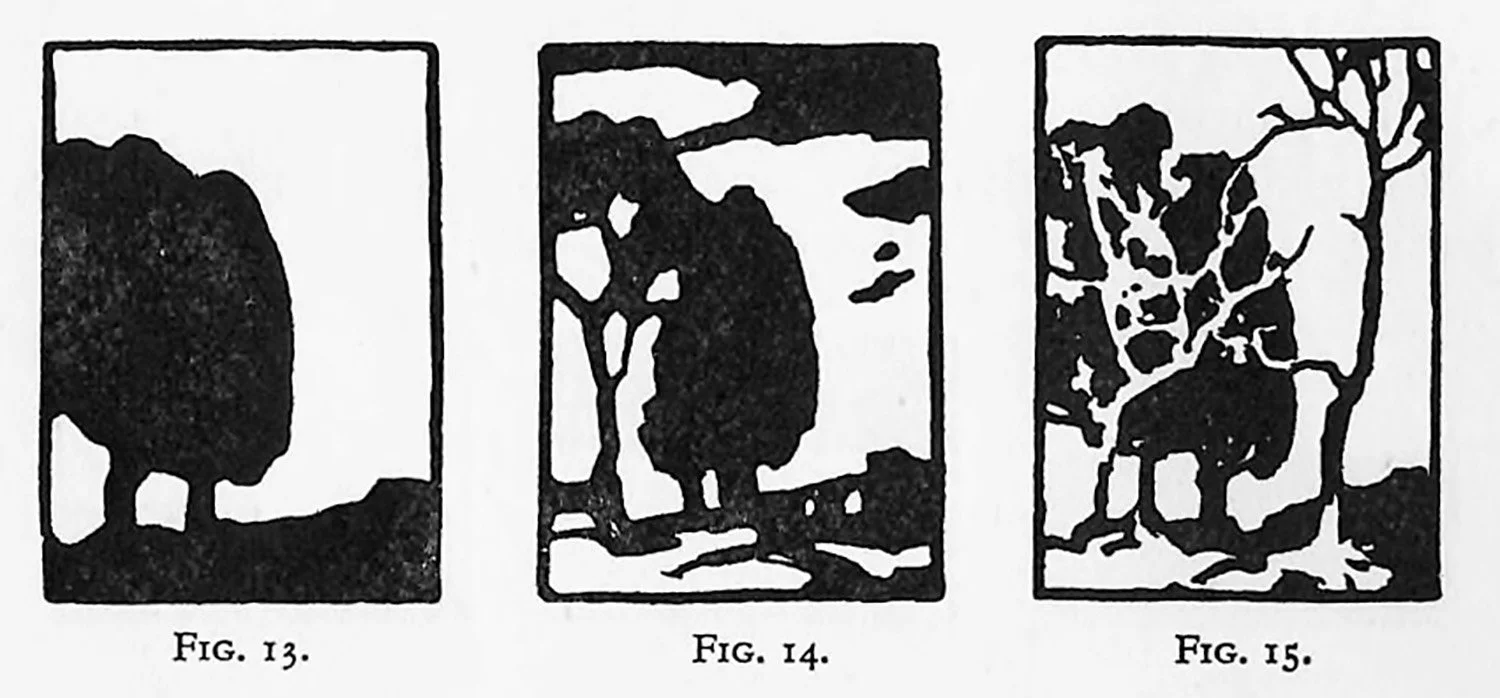

Once this principle has been assimilated it becomes apparent in almost everything that is seen in Nature. The light sides of objects are often seen against dark backgrounds, whilst the dark sides of the same objects are contrasted with a light ground. Light trees against dark trees, and dark trees silhouetted against the sky, may be seen at one and the same time.

Often a tree that is light in its lower portion against the dark background reverses its arrangement on its upper portion by appearing dark against the sky.

The same figure that is seen lit up by the sun or the street lamp moves into shade and becomes dark against some light background. This interchange is one of Nature’s ingenious methods of giving variety, and the student should have no difficulty in finding many such examples.

There is one thing that must be especially noted. The employment of interchange usually makes for naturalistic representation, as shown in Figs. 13, 14 and 1s, and the student who wishes to design with dark and light—without light and shade—must be on his guard or he will find his two-dimensional scheme becoming three-dimensional in certain parts of his work. Shapes that, as explained in the first chapter, suggest rotundity are apt to creep in. Even when gradation is absent, interchange can sometimes, with its attendant forms, bring about this trouble. If the accompanying illustrations are studied it will be clear that interchange can be used with great effect, even in the more abstract condition of the two-dimensional decoration.

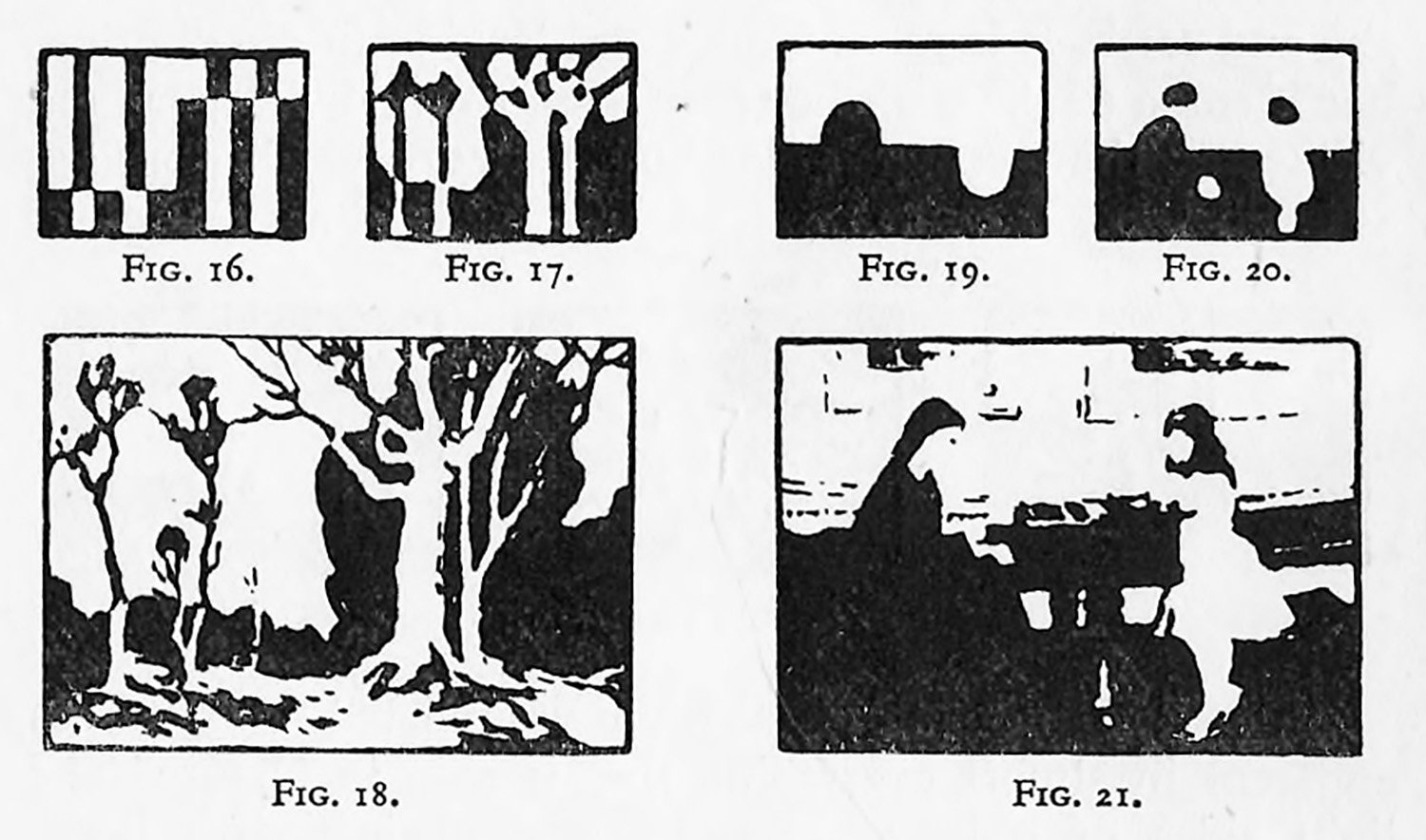

Figs. 16 to 21 show two pictures—one by Harpignies and the other by Whistler—analysed to illustrate the principle of interchange.