Chapter XIV.

Rhythm

“Once we have command of rhythm we have command of the WORLD.”

— NOVALIS

WHEN all the factors that individually make for good composition have been considered, a vitalizing impulse, which we will call rhythm, is still required. It is important that every artist should attempt to recognize and make use of such a powerful aid to composition.

Rhythm in the limited sense means flow—in music, the movement in musical time or the periodic recurrence of accent. It gives a succession of impulses, sounds, and accents in poetry, and in the larger sense it can be felt in Nature, in the succession of the seasons, in our progress through life from childhood to old age. The word “rhythm” has become almost significant of life itself. It is in the dance that the artist is first attracted to rhythm in the form sense, for the dance combines both the measure of time and movement in space. Rhythm cannot be expressed until it is experienced; a course could be arranged in which movements of the body were given special attention in combination with drawing.

If we run, run and turn, tun and twist, move our arms, hands and wrists, it is possible to experience curves, spirals, forms with corners and angles, wave-lines, expansion and radiation. A coutse such as this might take us nearer to coherent expression and form a track away from the dull, patient copying of objects. Even this would be only a beginning, for the mind must be taught to observe the vital and characteristic form-content that lies at the back of external things.

Rhythm in art gives a movement or condition of line that takes hold of all kinds of apparently irrelevant details and gives them coherence. As thythm in verse helps the mind to hold on to ideas in a collective manner, so rhythm in form helps us to grasp and relate many otherwise separate conceptions.

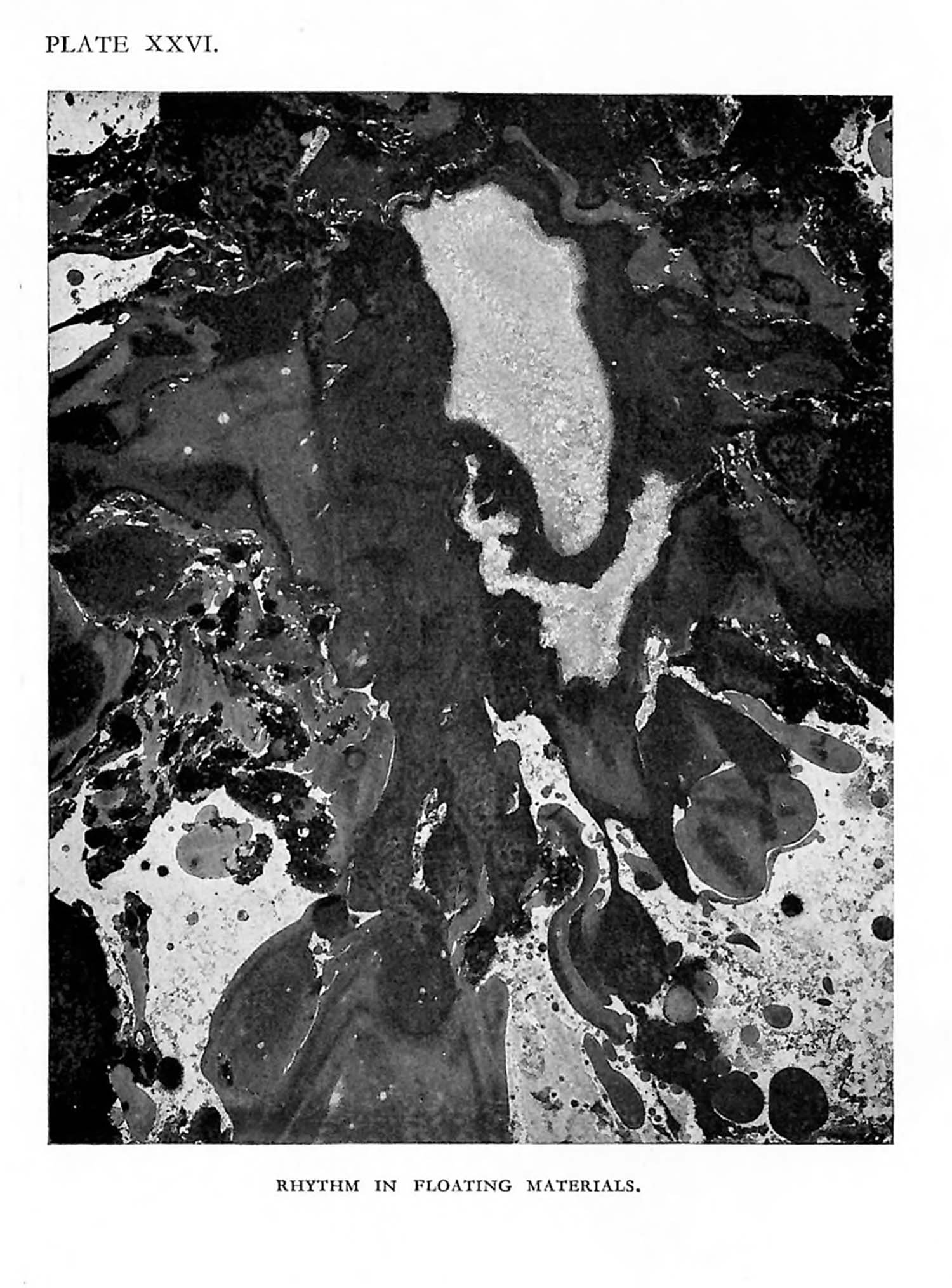

Let us start with simple or easily-observed rhythms such as may be seen when we consider movement, or impulse, against the adjacent conditions. If permanganate of potash ctystals are dropped into water and shaken we see red streaks curl and wind themselves in the water. The forms in movement will be alike in general character. Salts that effervesce when dropped into watér give a violent upward movement. Cigarette smoke in a quiet room shows us fantastic ascending forms of a consistent character. If colours mixed with oil are dropped on to the surface of a basin of water they float, and a splash or directional push of the water at the edge sends the materials floating on the surface into a pattern in accordance with the impulse given to the water. If paper is carefully placed flat on the surface of the water the patterns can be transferred and examined at leisure. Plate XXVI is an example. The old-fashioned wavy and spotty end-papers used in bookbinding were obtained by a modification of this method.

The consistency of these patterns should be specially noticed. When we observe the larger forms in Nature this sense of the characteristic must still be retained. The sea, with its undulations, its crossings and te-crossings, is an excellent example of consistent impulse. When the sea is remembered we become aware that behind the incidental there are the characteristic or constant forms, and it is these forms that are the most important to the artist. If we attempt to draw the conditions of form mentioned, out hands, wrists and arms should feel a kind of freedom. We are necessarily drawing from memory, and the line flows. The unimportant incident is submerged in the characteristic, and there is no hindrance. It is when the factor of time slows down that the student’s efforts relax.

There is just as much characteristic impulse in the distant line of mountains as in the sea, but often the incidental forms gain in importance—are given undue expression—and the majestic sweep is interrupted.

The above statements might be thought to imply that memory-drawing is advised as a method of approach. This is certainly not the case, for what is really required is the sense of rhythm when we are faced with the actual objects. The freedom that is sometimes shown in memory-expression only proves that the sense of rhythm is embedded. It must become a conscious activity.

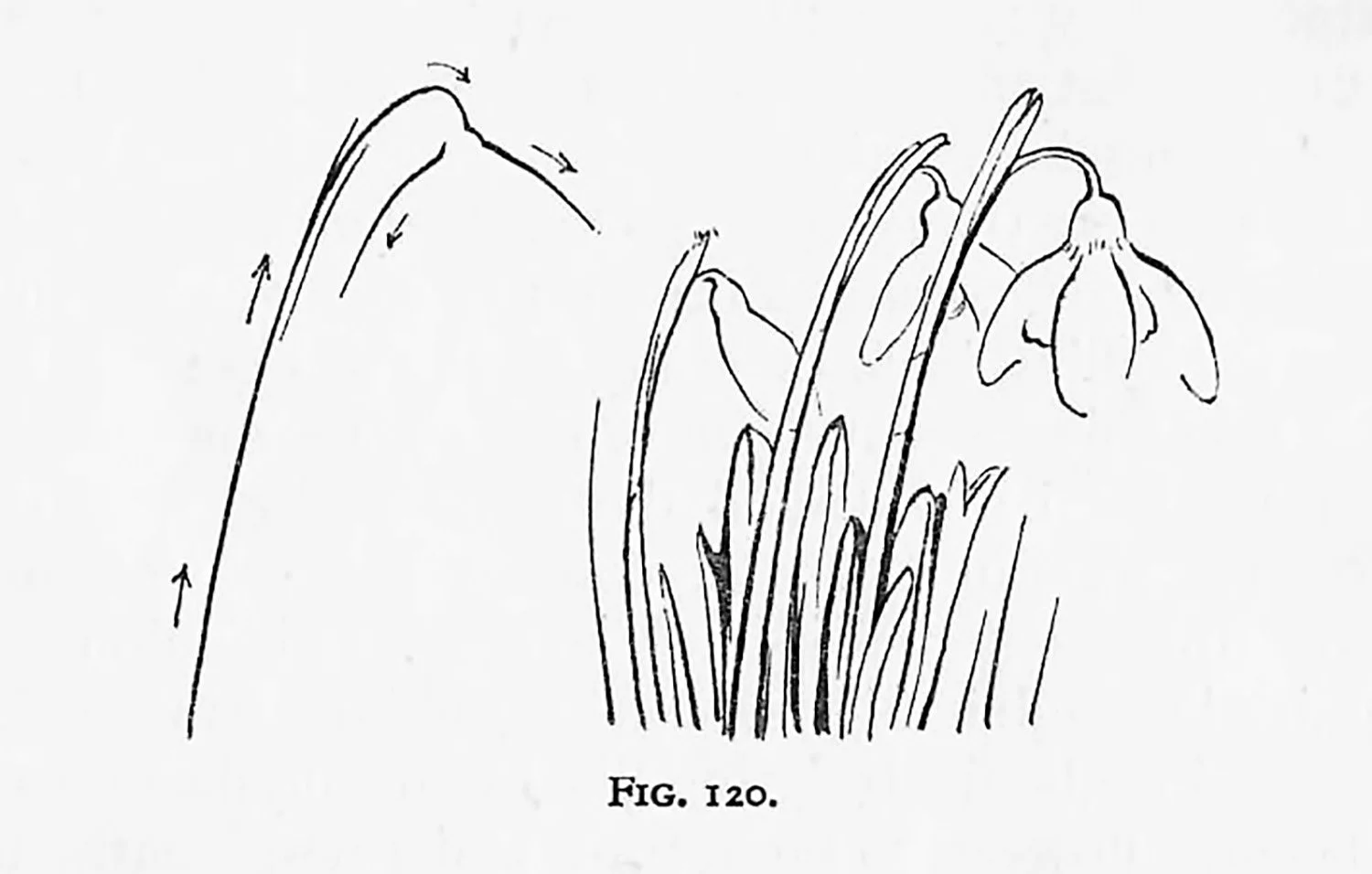

Every year, as the seasons go by, we find the rhythm of up-springing, of coming out, in the spring, and in the autumn the falling back or going in of the vegetable kingdom. If we really sense such movements when the snowdrop, the crocus, the daffodil, and the other spring flowers are coming up we ought to be conscious of a tremendous upward thrust—a rocket-like activity. Ridiculous and undignified though it might seem, it would pay us aesthetically to become imaginatively spring-like in our physical activities—to become flowers, to burst forth and attempt eurhythmic expression. Such characteristic impulses and their attendant forms seem to be submerged by detailed scientific knowledge. The nature of the bulbs, the sheath, and the shapes of individual parts, with their botanical names, are well known to students, and may be useful in their own way, but they must not be allowed to take the place of the consciousness of the vital movement.

We find the student drawing external individual shapes of a snowdrop, the forms being drawn without any appreciation of impulse. The training suggested would draw lines upwards in the manner indicated in Fig. 120, just as one would see a rocket go up and break into stars. After all, the impulse is not dissimilar, for if a plant like the snowdrop grew quickly under our eyes the beforementioned conception would be readily understood.

The finished picture rarely equals the sketch because of the difference in the time factor. The impulses slow down and become side-tracked: the picture becomes a machine that often does not work.

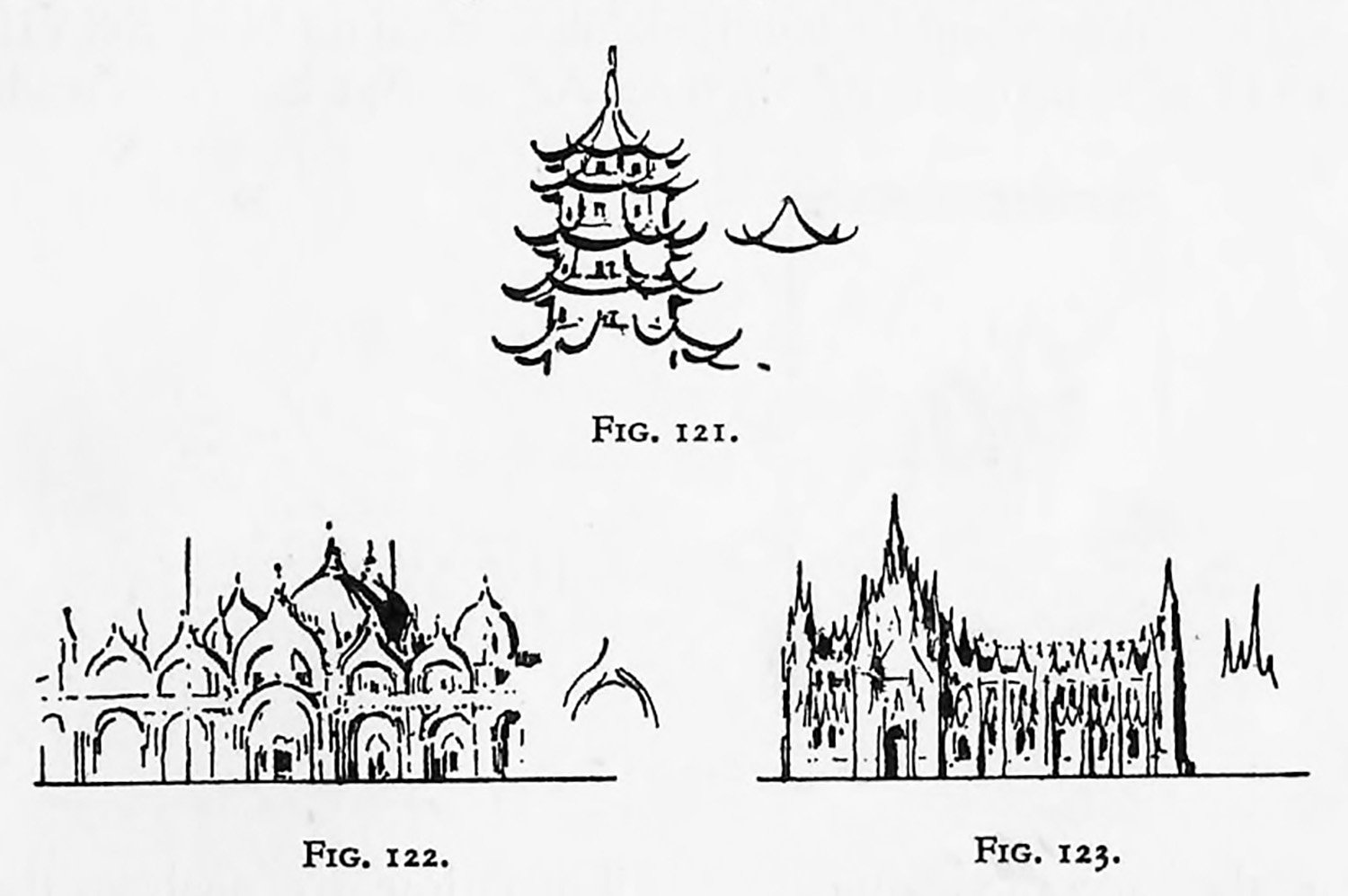

It may be thought that consistency of form with the necessary variety in repetition would meet the requirements of rhythm. On reflection, however, it will be seen that what is required behind consistency and repetition is a conception of characteristic impulse. We must draw our forms in the direction of our thoughts, and this impulse should knit the smaller characteristics of individual forms so that the decoration shall become an indivisible whole. If we carry these ideas into the examination of an epoch it will be found that we lighten up archeological research in a remarkable manner, for it seems as if the great periods in history were in favour of, or limited to, certain characteristic rhythms; for instance, the heavy wedge-like rhythm of the Egyptians manifesting itself in architecture, costume, and jewellery, to the commonest detail; the clear-cut, precise, rectangular, and vertical characteristic of the logical Greeks; the constructive rhythm of the Romans shown in their semi-circular or dome-like works; the ogee rhythm of fourteenth-century architecture, as shown in St. Mark’s; and in our own country we find the pointed rhythm of the medieval builder, which Mr. G. K. Chesterton so aptly describes as the symbol of the church militant. It must not be forgotten that such spear-like forms go right through the life of the period: the steeple hat, the monk’s cowl, the weapons, the pointed shoes and sleeves.

It has been thought by some that the religious life or the prayerful attitude of such times dictated the outward forms from some inner impulse. Later we find the uplifted beseeching attitude silhouetted in windows and doors has given way to one of thoughtful challenge in the earlier forms of the Tudor period. The posture of the arms on a table with the head resting in the palms certainly suggests the Tudor arch. The costumes, again, agree with this impulse. The diamond-shaped Elizabethan impulse could in its turn come up for discussion. These remarks, however, need not be taken as conclusive, but rather as the basis of a suggestion for a new line of esthetic research. Figs. 121, 122, and 123 indicate three forms of architectural rhythm.

It must not be assumed that only such forms as those mentioned were used, for every other form was probably used in some measute. It is the bias or rhythmic impulse in form of a given age that is referred to. Whether such a bias as that suggested is agreed to or not, it is clear that it is the individual impulse that should assert itself in all good composition.

Every individual has his varying emotions and impulses, and it is the business of the painter and the artist generally to understand the esthetic equivalent of what they see—its line, tone, and colour-equivalent—in order that impulses may be adequately expressed.

If we examine pictures, bearing rhythm in mind, we shall find that all the great artists, either consciously or subconsciously, obeyed this rhythmic impulse.

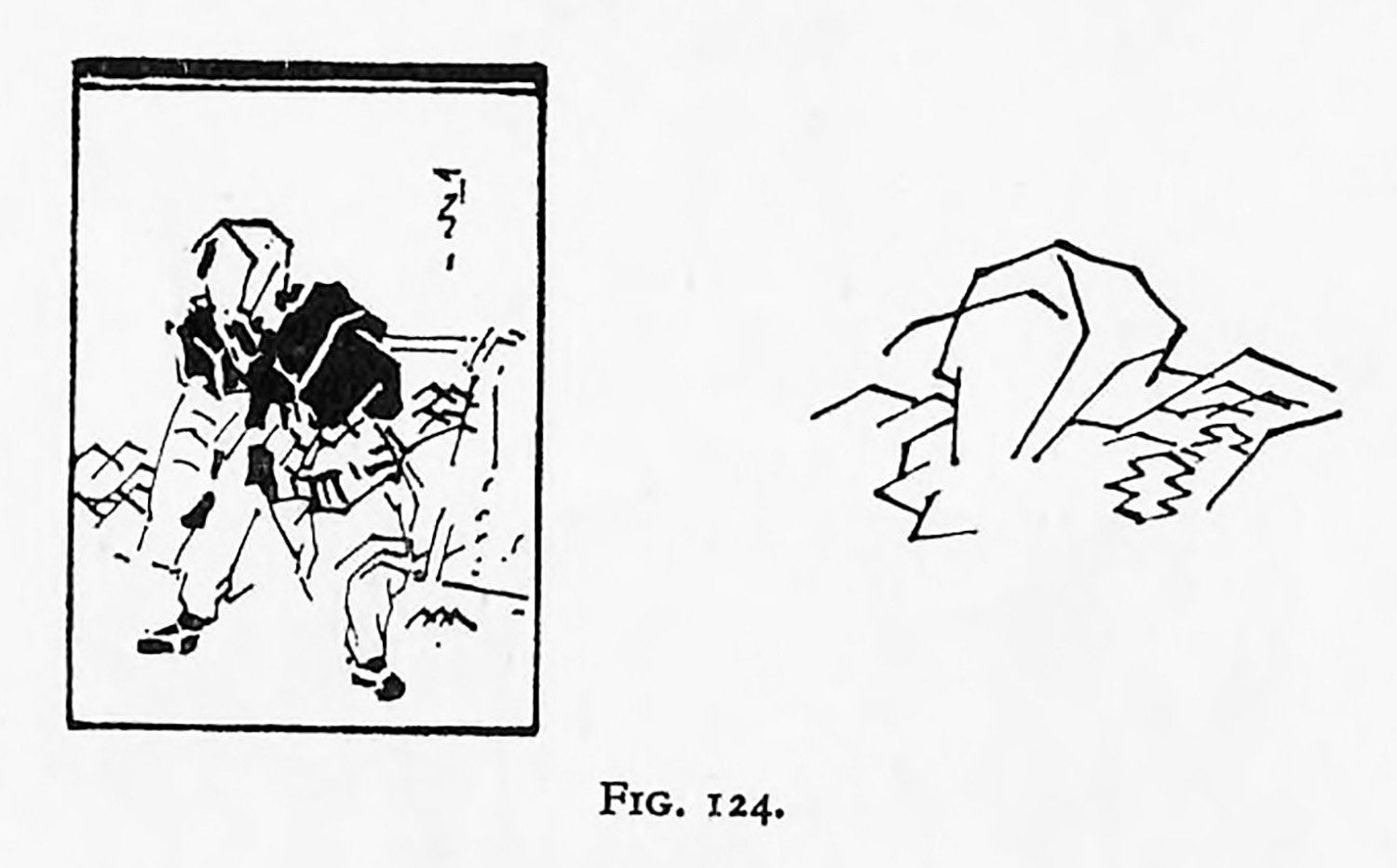

The colour-print by Kunisada, illustrated on Plate XXVII, is full of a wide-angled rhythm. An attempt has been made in the accompanying small illustration to analyse the impulse (Fig. 124).

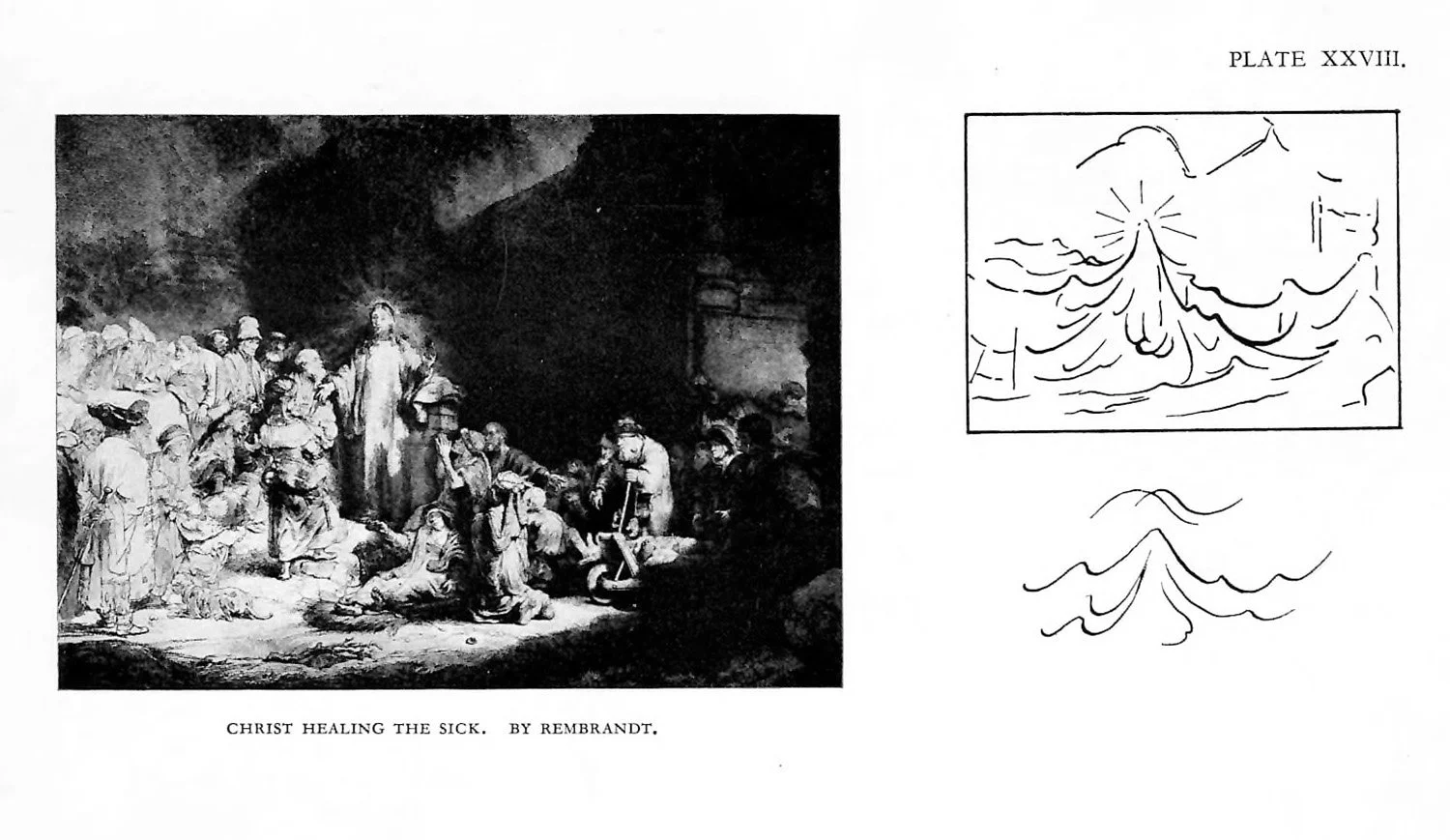

The illustration on Plate XXVIII shows the well-known etching, Christ healing the Sick, by Rembrandt. Here we find a wave-like rhythm culminating in the figure of the Christ.

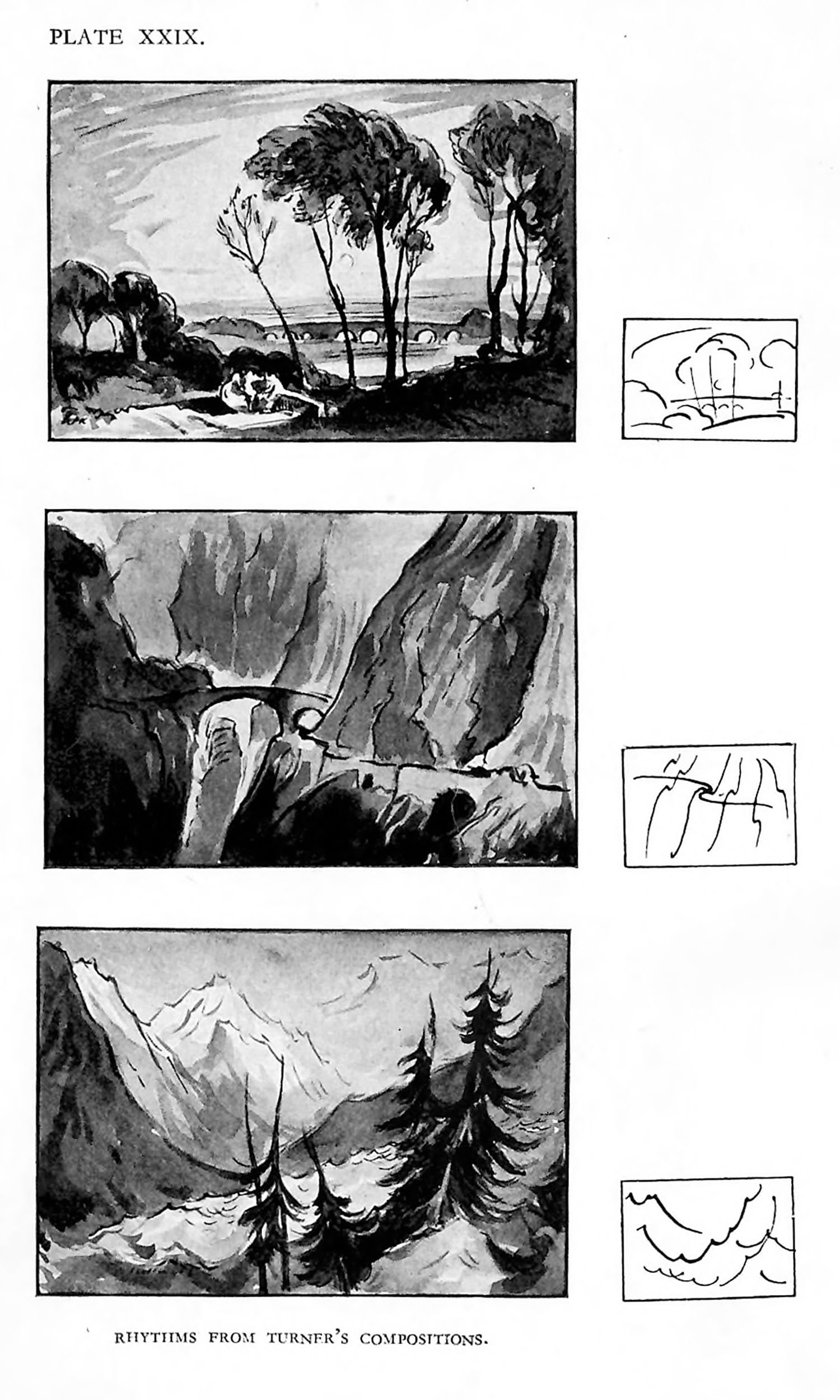

On Plate XXIX three compositions from Turner’s Liber Studiorum are given, and the student should find no difficulty in following the analysis of impulse shown in each small illustration.

It may be said that a special sense is required to recognize rhythm; yet it is the author’s experience that every earnest student, sooner or later, develops such an appreciation of impulse.

Rhythm in art is sometimes called “style” or “individuality,” and in its outward manifestation such terms may be correct.

In any case it can be confidently asserted that when what is here called rhythm is fully appreciated we are getting nearer to the true heart of composition.