Chapter XII.

Perspective and Composition

NO attempt will be made in this chapter to teach perspective. There many text-books on the practical application of its laws. It is our business as students to understand perspective, and then, having mastered its principles, to use it to express our ideas.

Perspective might be termed the logical rendering of three-dimensional ideas on a two-dimensional space. It gives apparent depth and imparts to the units the correct size and aspect in relation to the supposed distance within the picture. Many nations have ignored perspective in their art, and several present-day artists consider its importance greatly overrated and tending to obscure the true aesthetic sensations that it is the business of art to express.

It was during the early Renaissance that formal perspective began to be considered necessary (although many of the Oriental works and some of the paintings from Pompeii show an amazing grasp of some of its essentials), and it is then that we find the real urge towards naturalistic representation.

From that time until quite recently perspective has held an important place in art training. Leonardo da Vinci left statements regarding the angle of true vision, outside of which distortion occurs. Turner was the teacher of perspective at the Old Royal Academy Schools, and he is said to have discoursed obscurely about domes and shadows. There can be little doubt that whilst objective art is practised it will have to submit to the laws of recedence, or perspective. In the composition of pictures it becomes a factor in limiting the size of relative areas. This is a very disturbing factor sometimes, yet. when tecedence is required it gives one form of intellectual satisfaction and consistency to the work.

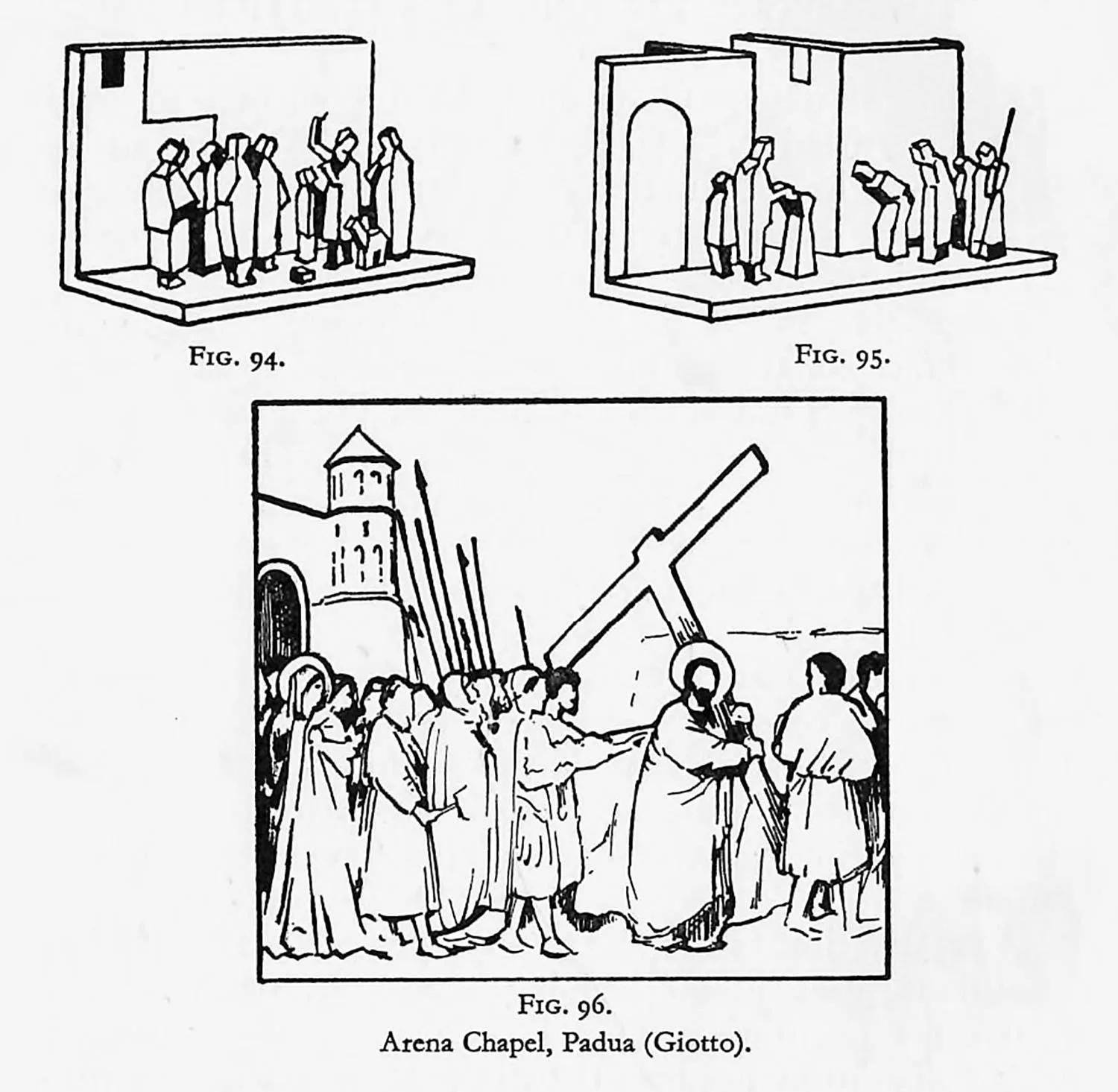

Let us see how the designers in the pre-perspective era composed. If a narrow stage with a vertical background be considered we have the usual environment, and if on this narrow strip we arrange our figures we find, perhaps, the simplest conditions under which pictures can be composed (Figs. 94 and 9s), reminding one of the sculptured friezes of the Greeks.

Figures under such conditions were often given a fair amount of solidity or rotundity. The interest was usually centred on the personality rather than environment. When we regard these frieze-like compositions we find that the interest is close to the surface and almost two-dimensional in character, with drawing, colour and spacing (Fig. 96). These pictures give pattern considerable freedom, and it is no surprise to find that artists have from time to time gone back to such conditions to free themselves from the trammels of atmosphere and depth. Under such conditions of design combinations of colour can be arranged that would be incongruous and altogether lacking in plausibility in the atmospheric rival.

It is interesting to note that as perspective became more sought after the background of the pictures became the field of operations whilst the figures still remained packed up close to the spectator.

At last, after many experiments, the distance became manageable. The figures varied from close up to mere specks on the distant hills, the dome-like character of the sky became imperative, and at last line combined with pattern and colour recedence, giving us the illusion of open space instead of the original two-dimensional flat surface decoration.

If we discuss the practical use of perspective, a few outstanding facts must be taken into account.

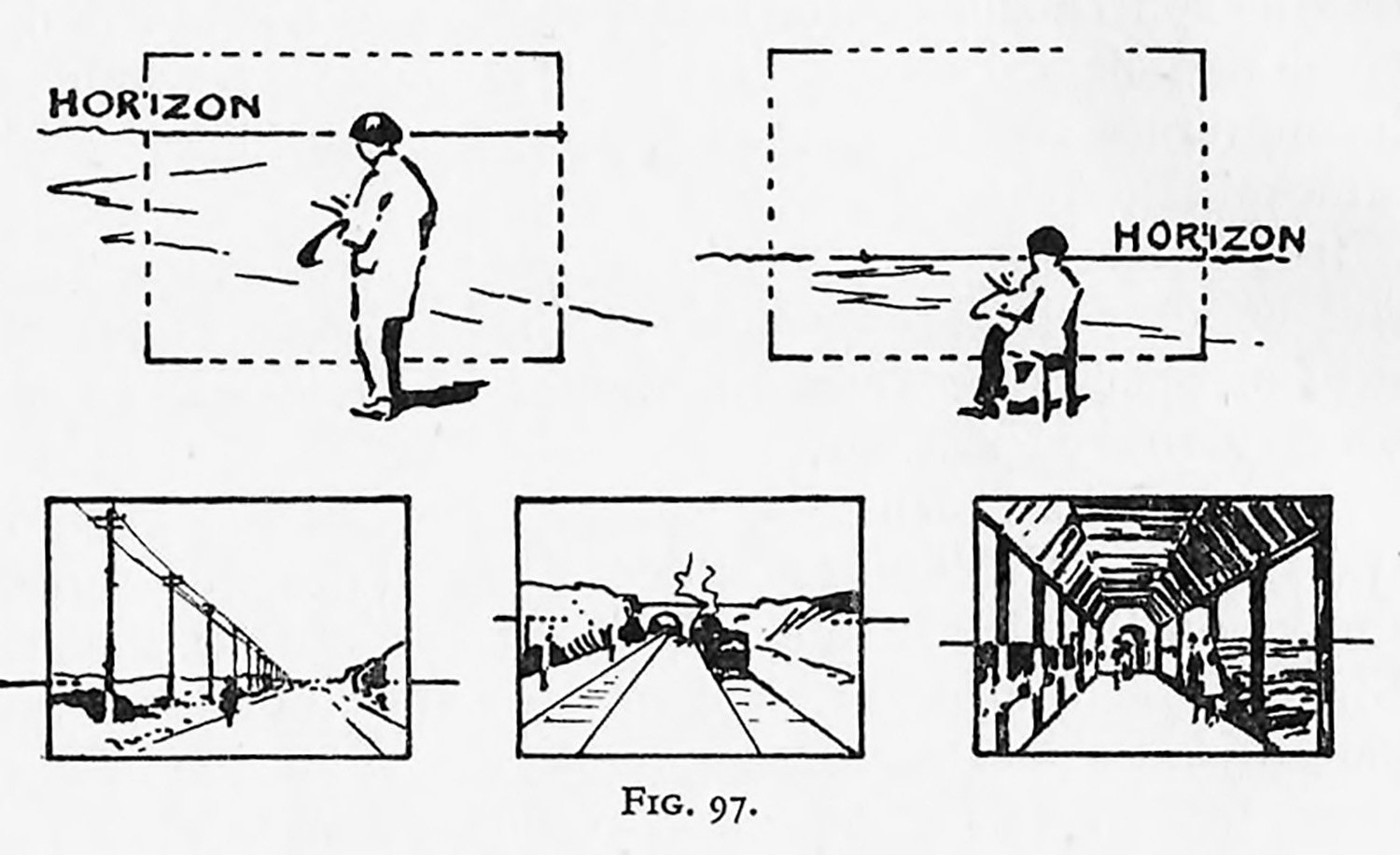

First of all, every picture into which perspective enters must be assumed to have a possible horizon or eye-level. This might be in the outside world—the distant sea horizon or the far edge of the level moor. On this theoretical line all receding horizontal lines find their vanishing-point; also all lines parallel to each other on this level ground apparently converge on the same point on the eye-level. Every student is familiar with such diagrams as A, B and C in Fig. 97, and is usually very much alive to the rules governing the measurement of such teceding lines. In practice, however, these tules become so modified by curves, hills and valleys that only a few outstanding principles can be conveniently applied.

One important idea is that when we requite depth in a picture, so that the mind of the spectator goes in and becomes enveloped on all sides with forms and atmosphere, the suggestion of a way in must be given to the flat surface of the picture. Line and direction of form are the principal agents in giving this illusion. The pathway, the stream, the sides of houses, pillars, ceilings, floors and many other well-used devices ate familiar to all who look at pictures. Yet even when the student possesses the knowledge of perspective necessary to give the correct recession it does not follow that such lines and planes are what we term “composed.” It will be convenient to teturn once more to our flat surface, and without any thought of receding lines Of perspective consider the nature of radiating lines; for radiation is common to both types of expression, two-dimensional and three-dimensional.

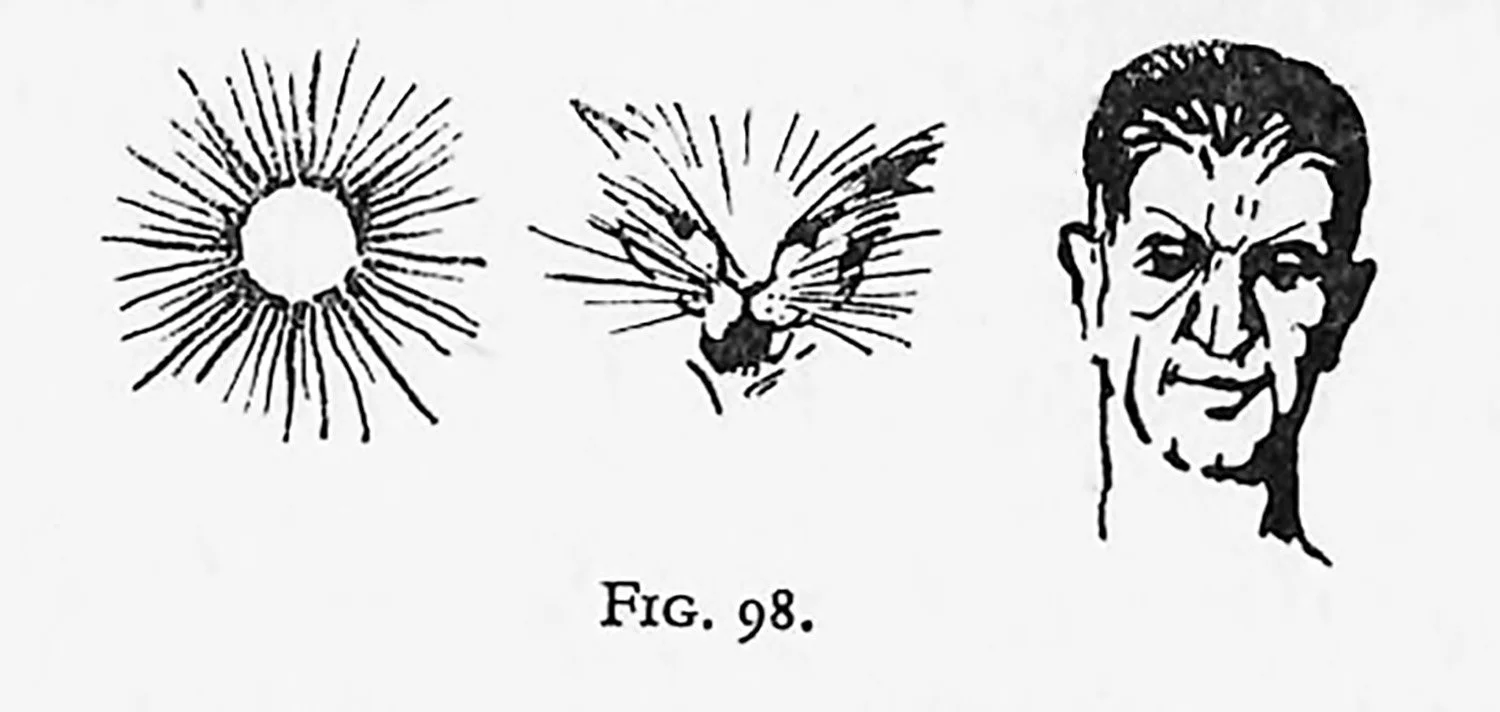

To state a familiar truth briefly: We know that when lines are arranged so that a concentration of direction is suggested the eye follows and is tempted to remain at this point of radiation, the rays of the sun taking us to the source of light, the radiating lines in the face of the human being taking us to the bridge of the nose and eyes, the radiating lines of most animals taking us to the mouth (Fig. 98).

To come to the abstract idea, it can be said that the lines that concentrate in direction without actually reaching the focus compel us to follow them. Converging lines that do not meet carty the eye to the point of convergence.

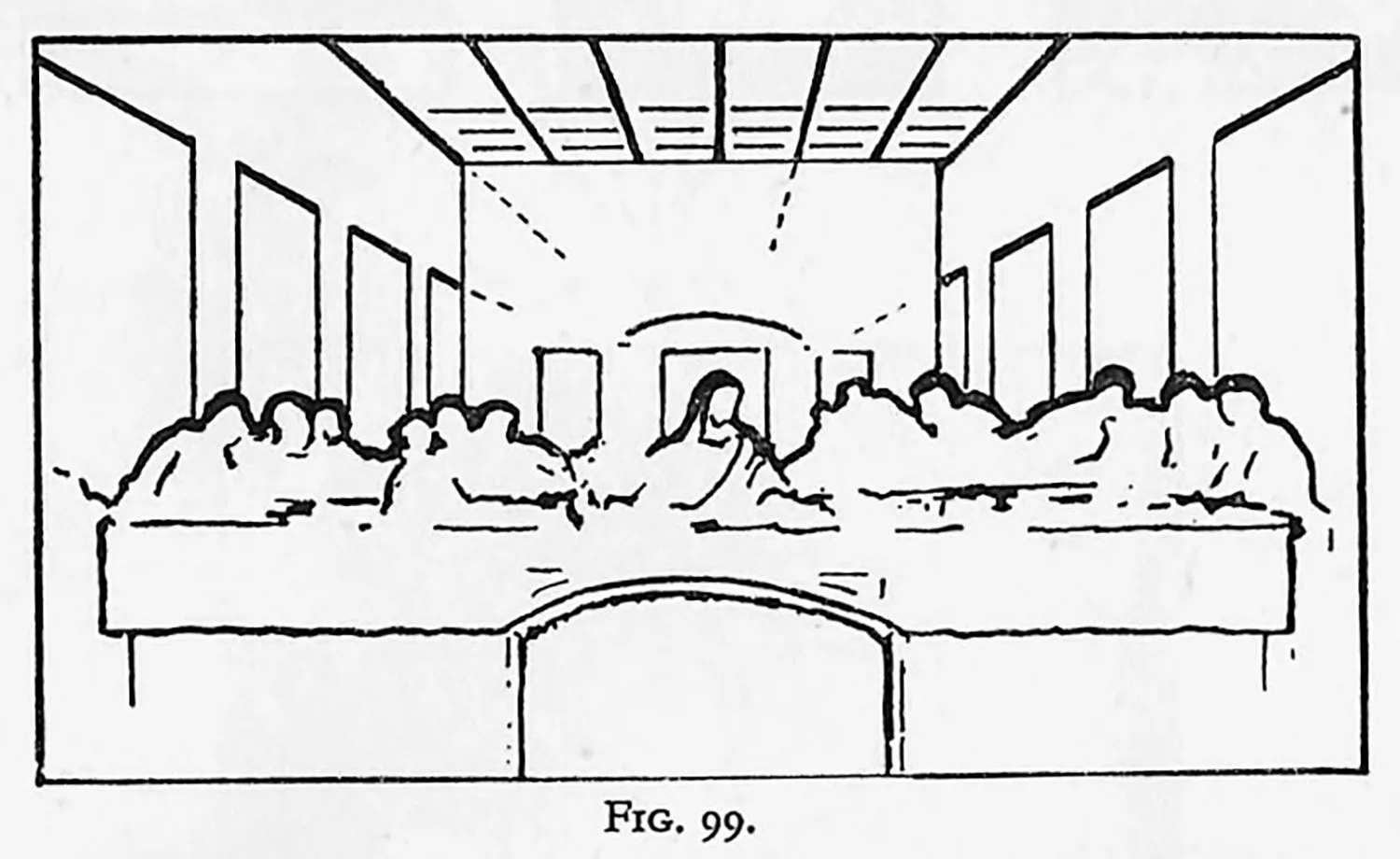

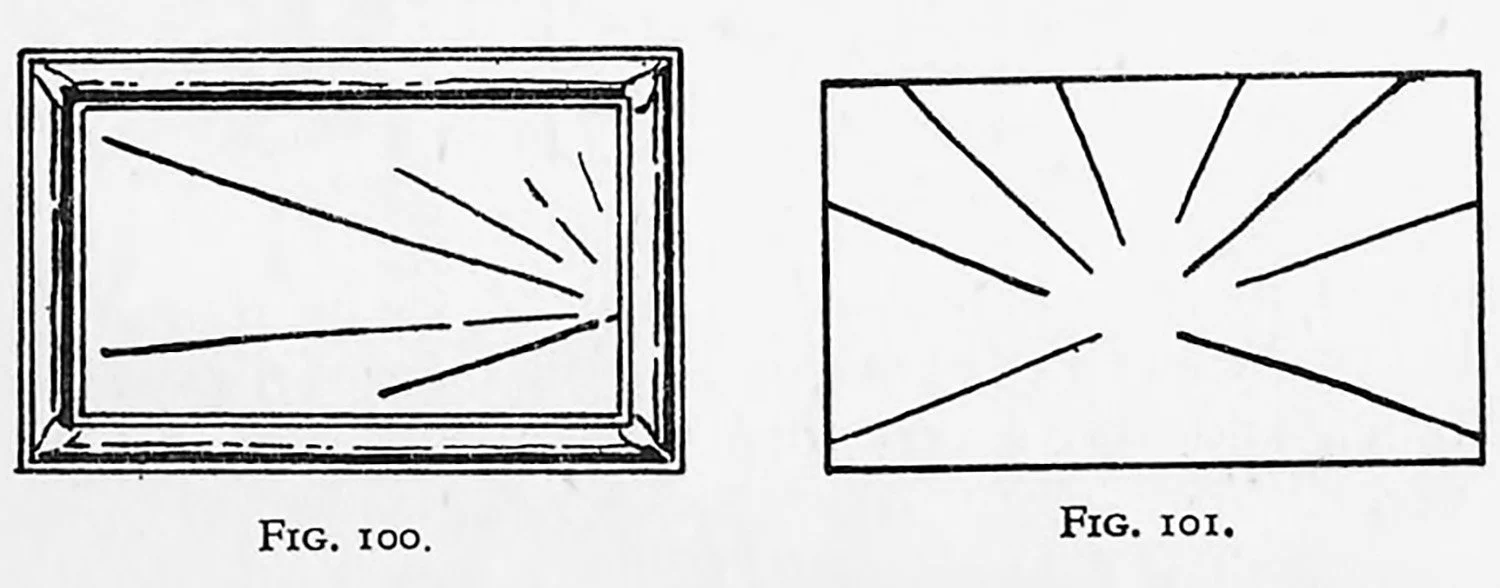

Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper (Fig. 99) is the classic example of the use of radiation (quite apart from the idea of perspective, which merely gives plausibility). Here the lines point to the Christ, giving pre-eminence to the most important figure. The lines are the edges of rafters, but the effect is the same as radiation on a flat surface. This fact is of vital importance in composition, for it is obvious that unless we control perspective we are not composing, but actually disintegrating our ideas, Let us take an extreme example. Suppose a scheme of radiation to be arranged as in out adjoining diagram (Fig. 100). This concentration of the radiating lines causes the spectator to exclaim, “What a nice frame!” and as the attention has been drawn to it by the lines within the contained shape the remark is not irrelevant. Such a radiation may be correct perspective, but it is bad composition. Again, let a point of radiation be placed centrally, as in Fig. 101. This is inclined to be monotonous owing to the equality of division on the sides of the suggested triangles, and only a very formal composition would justify its use.

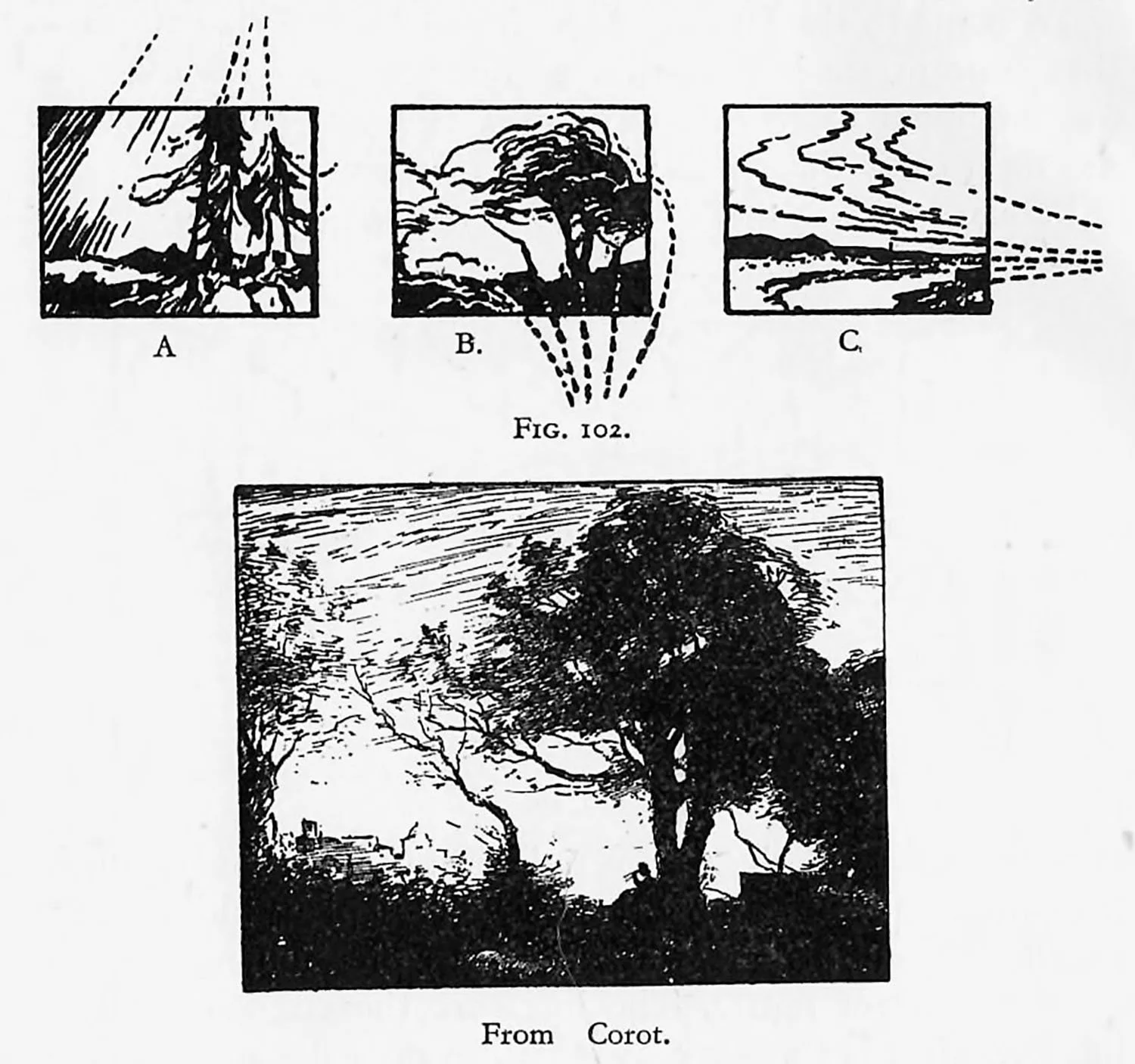

The point of radiation can, however, be placed outside the rectangle, and as long as the distance is sufficiently great we are not tempted to run away after it. Its value is important as a unifying factor. A, B, and C in Fig. 102 are examples.

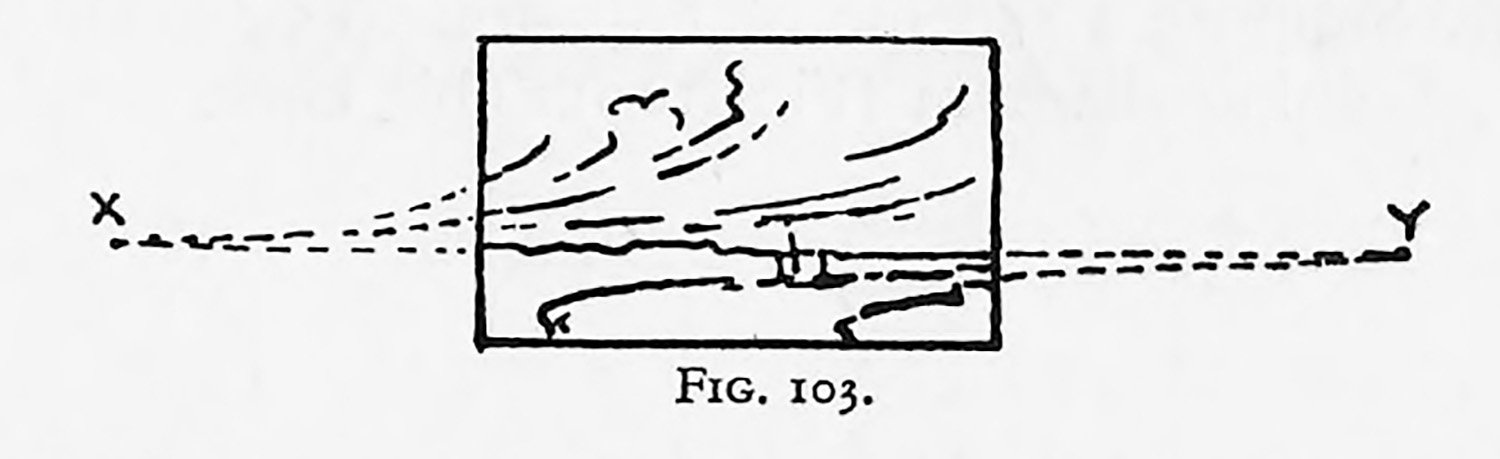

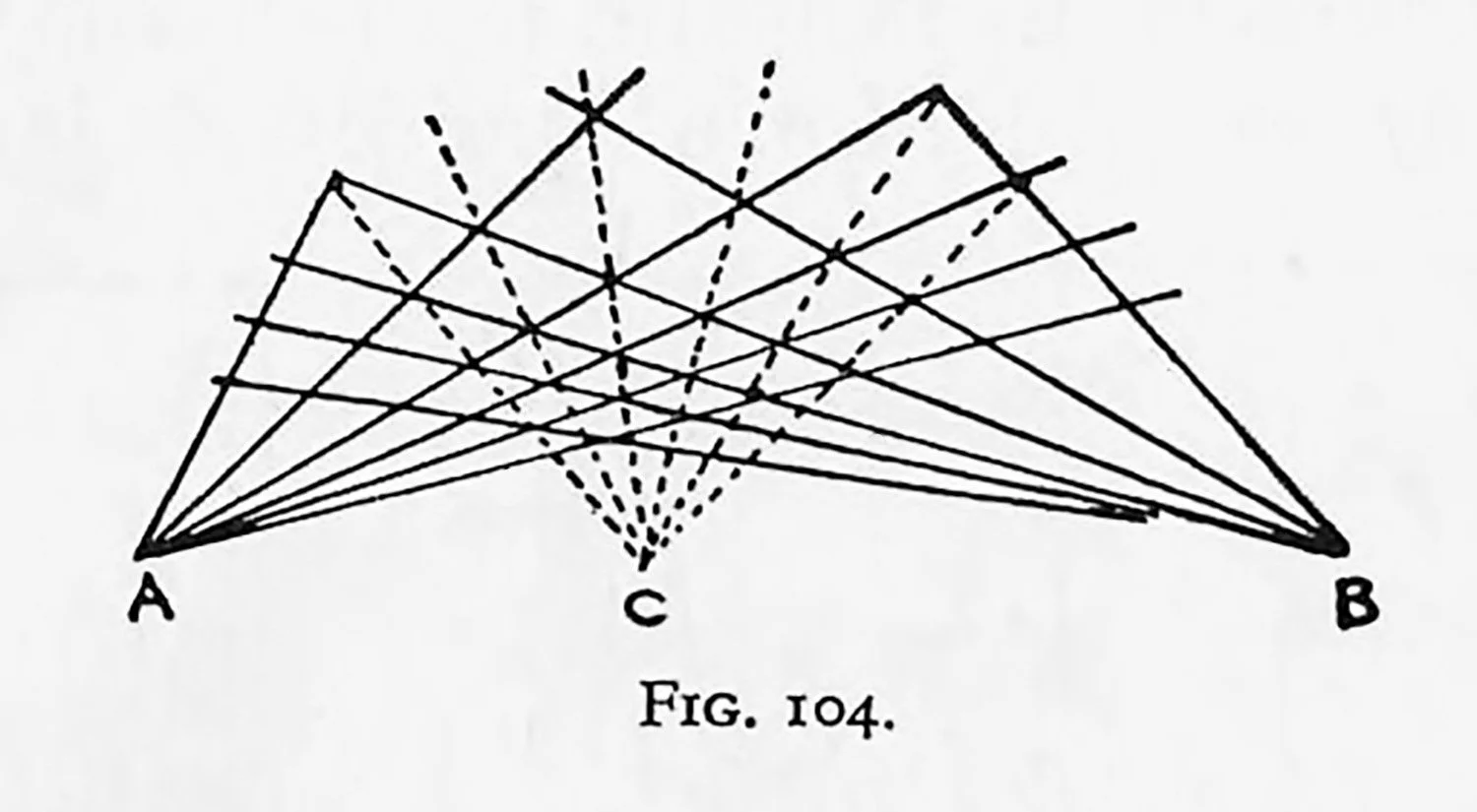

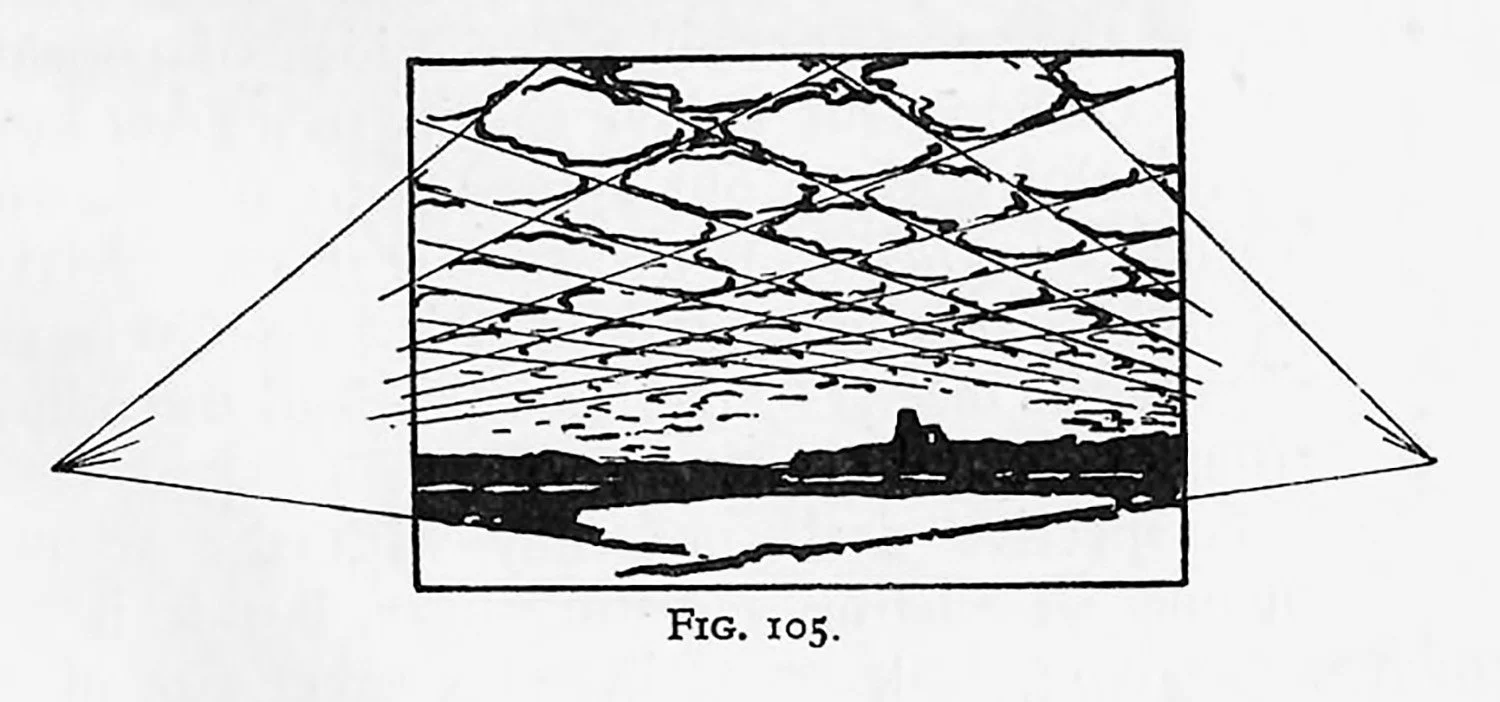

Now let us suppose that a picture is designed as in Fig. 103. This suffers because the lines are no longer unified as in C (Fig. 102), for the clouds drifting towards X and the banks going towards Y are no longer related. Hence we can say that if two points of radiation are to be used successfully they must relate to a third. A diagram will make this clear. In Fig. 104 the two points of radiation, A and B, cause by their interlacing the third radiation C. This is often seen in clouds, fields, and tiled pavements (Fig. 105).

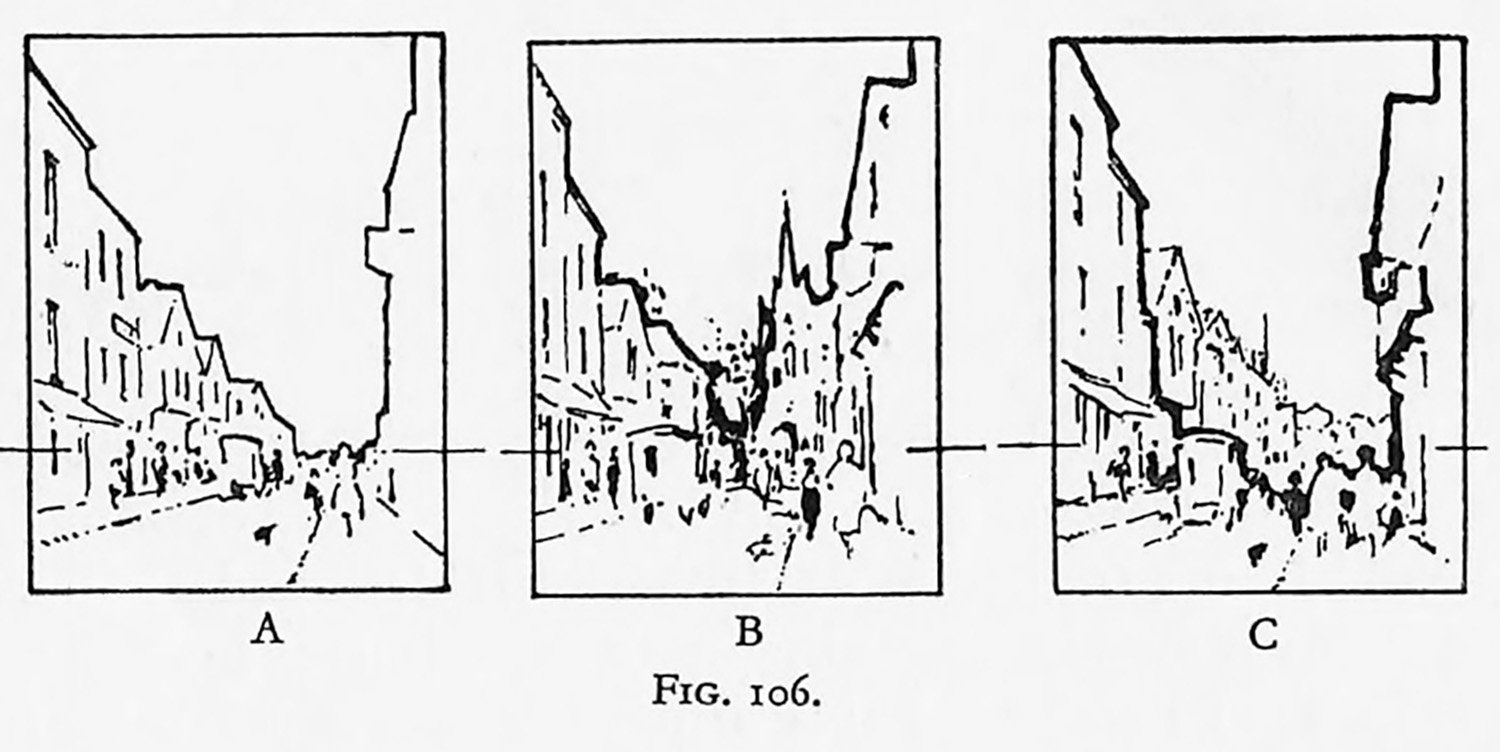

One of the commonest faults of the beginner is to arrange a set of radiating lines the focus of which is of a negative character. Compare A and B, Fig. 106. In A the lines have no objective. A beginner who discovers he has fallen into this fault should ask himself, “To what am I leading with my radiating lines?” and this will clear his intention. Composition, after all, is clear intention. It is, however, possible that a road or a river, seemingly interminable in character, is to be interpreted. In that case the radiating lines going out to infinity are justified, but considerable invention and ingenuity will be necessary to cause the delay of arrival. In B we arrive at something of importance. C shows a non-perspective solution, for the emphasis given to the contour distracts the attention from the distance.

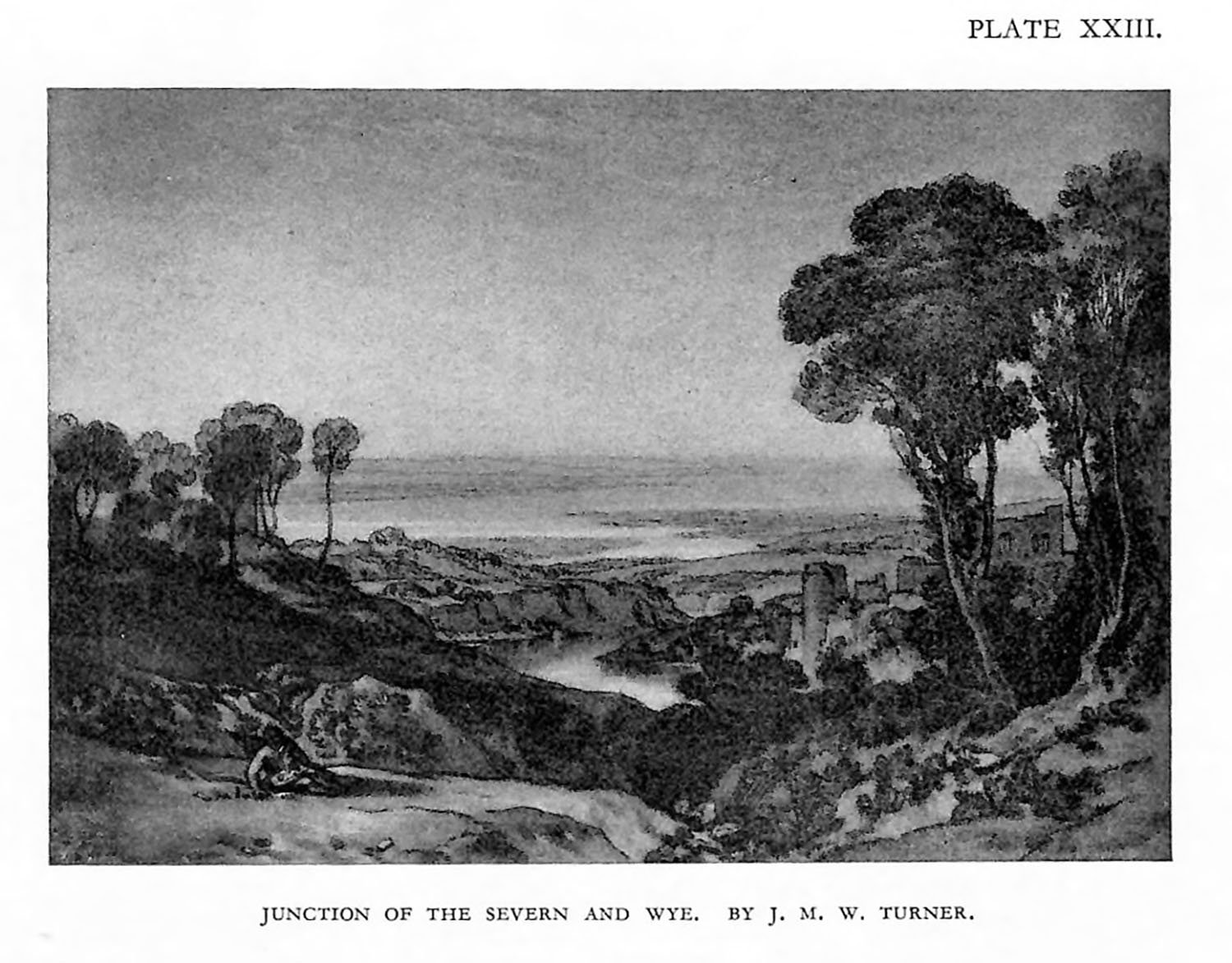

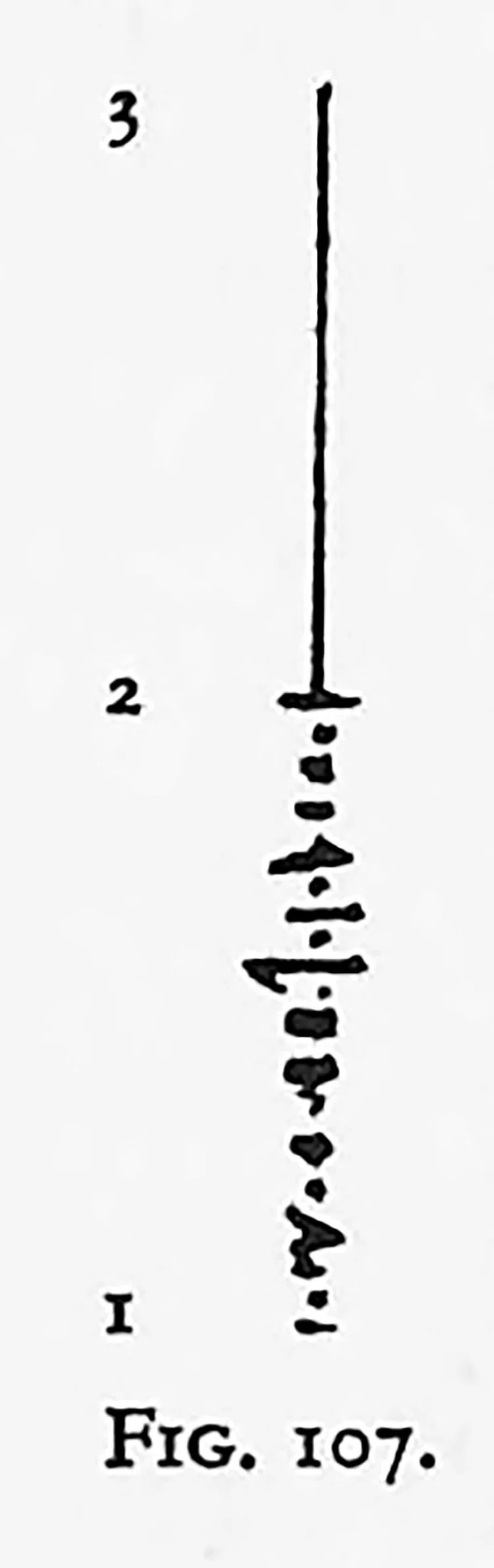

In the diagram (Fig. 107) 1 to 2 appears longer than 2 to 3, and in a similar manner we must cause interruption—plausible interruption—of all kinds before the spectator will feel the idea of considerable recession. Our enjoyment lies to a great extent in the slowness of our approach to the distance. Turner’s Junction of Severn and Wye (Plate XXIII) is an excellent example—indeed, Turner might be considered the master of methods that lead the mind to atmosphere and evanescent forms.

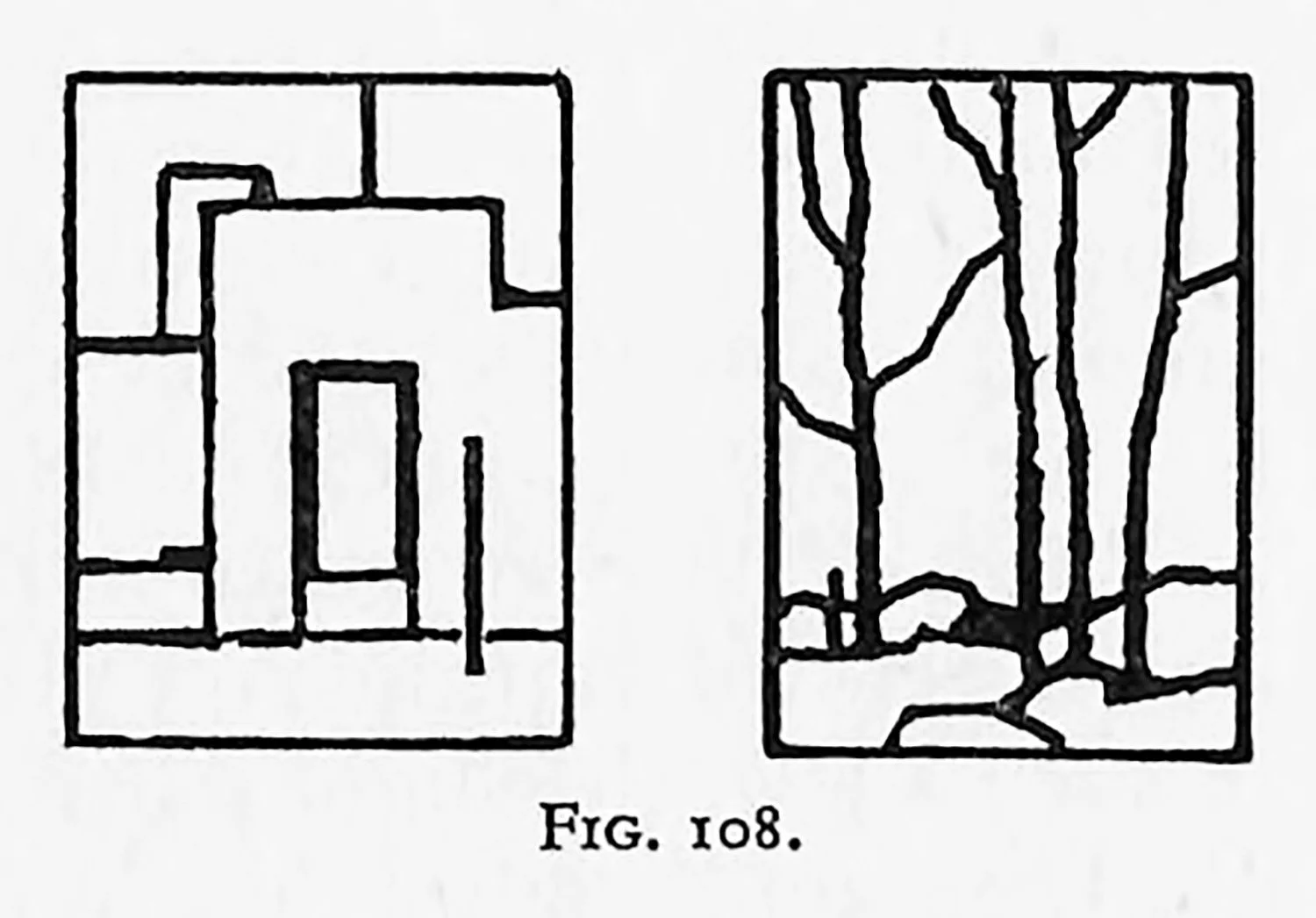

Perspective deals not only with the scientific manner of relating radiating lines, but it is concerned with giving scale—that is, the correct size of one object in relation to another. In the more abstract forms of composition scale is not determined by perspective laws. Thus if we are dealing with two-dimensional patterns as shown in Fig. 108, although scale exists, such relations can only be discussed by plane geometry, but the moment recession is suggested the work comes under the yoke of perspective.

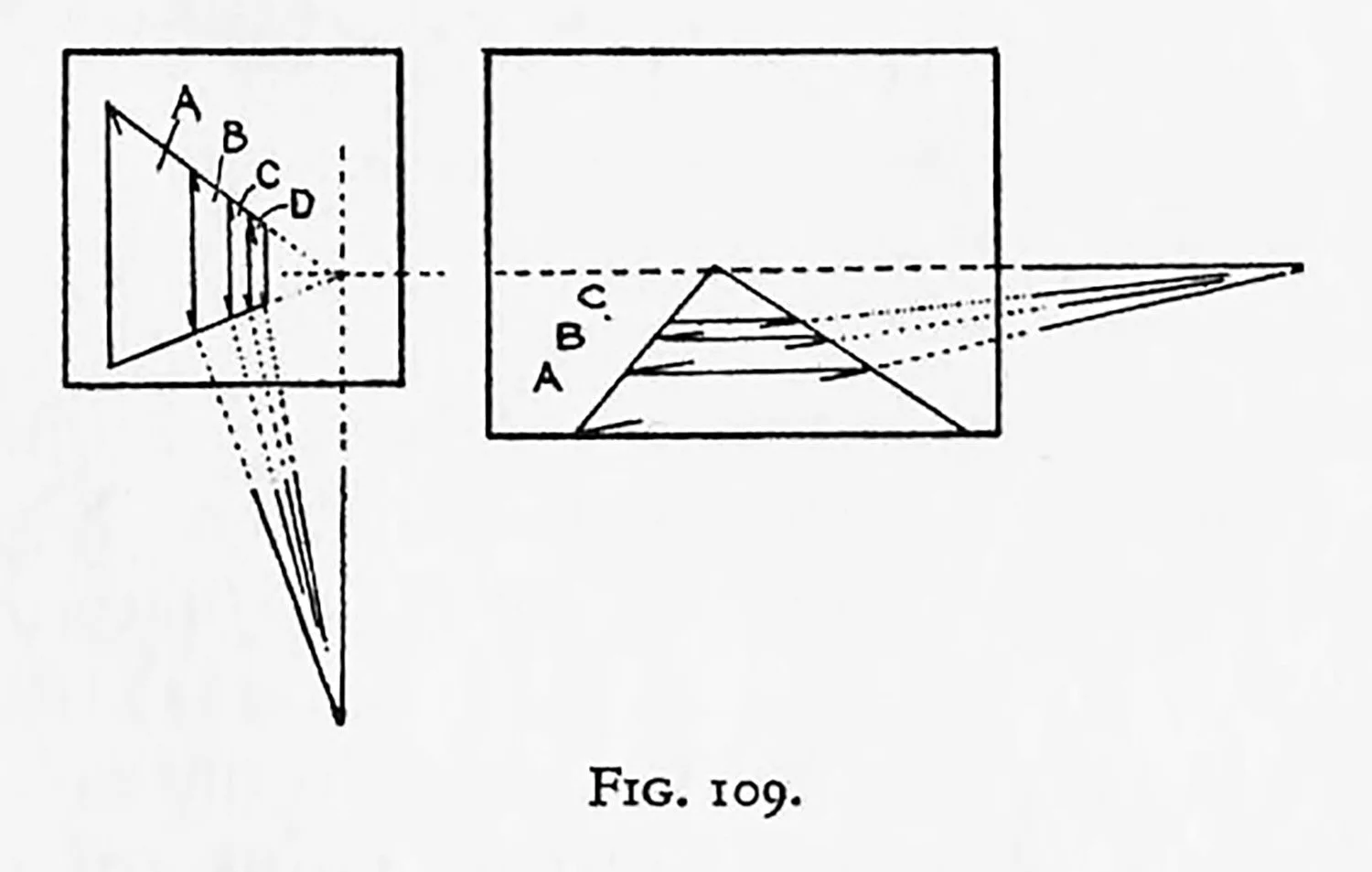

The shape A in the illustrations of Fig. 109 is known to be a rectangular shape with B, C and D actually equal to it. Then, after A has been determined, B, C, and D are mechanically marked off and made “‘consistent” with A. This is one phase of perspective. It should be noticed that such a condition, which is necessary if we are faithfully to represent recession, imposes a considerable curtailment of our freedom of choice, inasmuch as certain shapes are inevitable.

Whilst accepting perspective, artists have always had a suspicion and a dislike to being driven in the matter of consistent formal perspective design. Turner kicked over the traces when in his Dido building Carthage he used the shadows from two suns. Whistler effected a compromise between the two-dimensional free patterns of the Eastern artists and our more naturalistic Western art. In his Mother, Carlyle, and Miss Alexander and other works we find a deliberate “closing up” of the recessional planes, and in this one respect we have something like a return to Giotto. But although Whistler’s work perceptibly approached the two-dimensional type, his colour and tone still retained their three-dimensional character. Pioneer though he was, he did not achieve the complete victory.

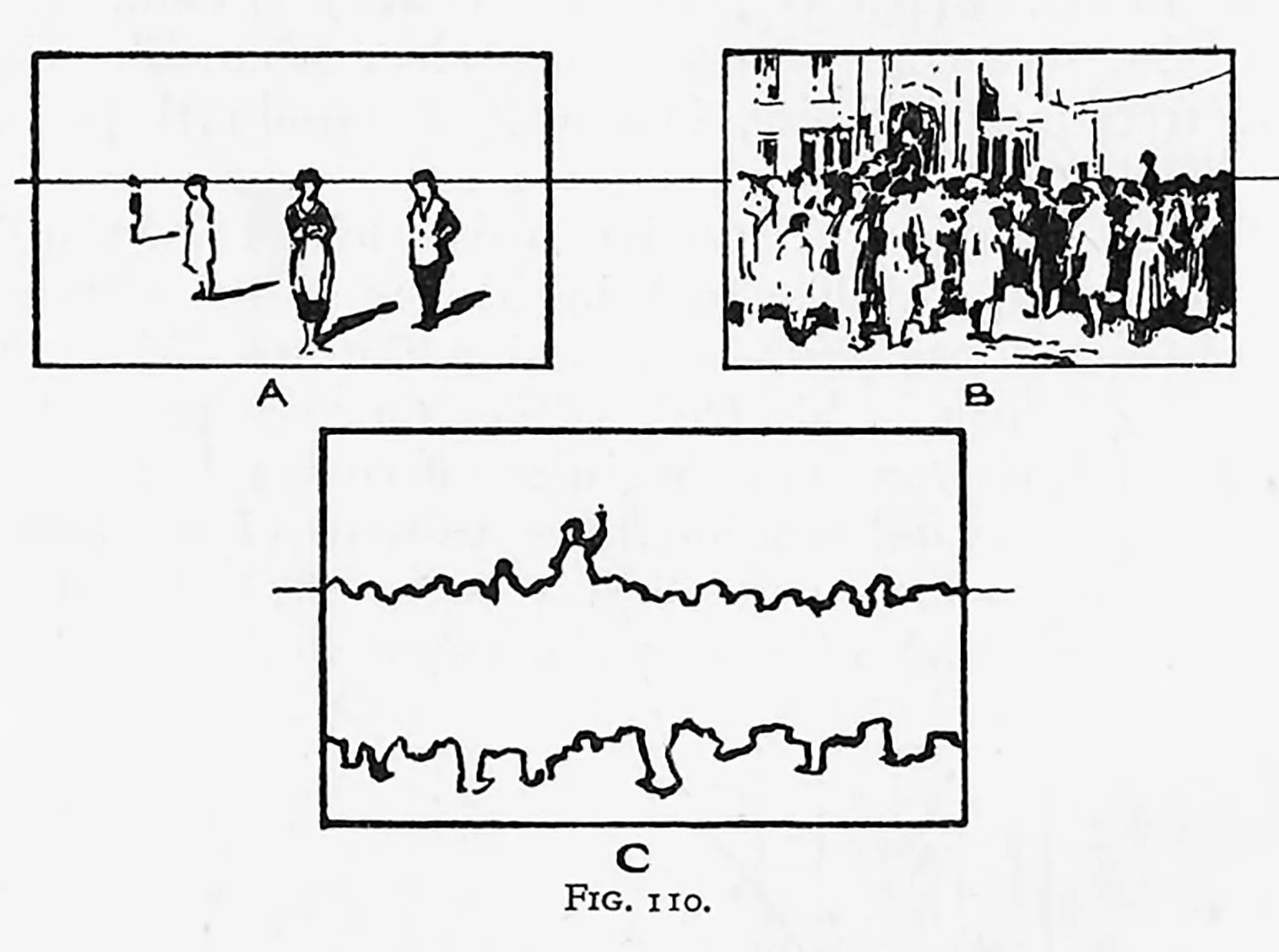

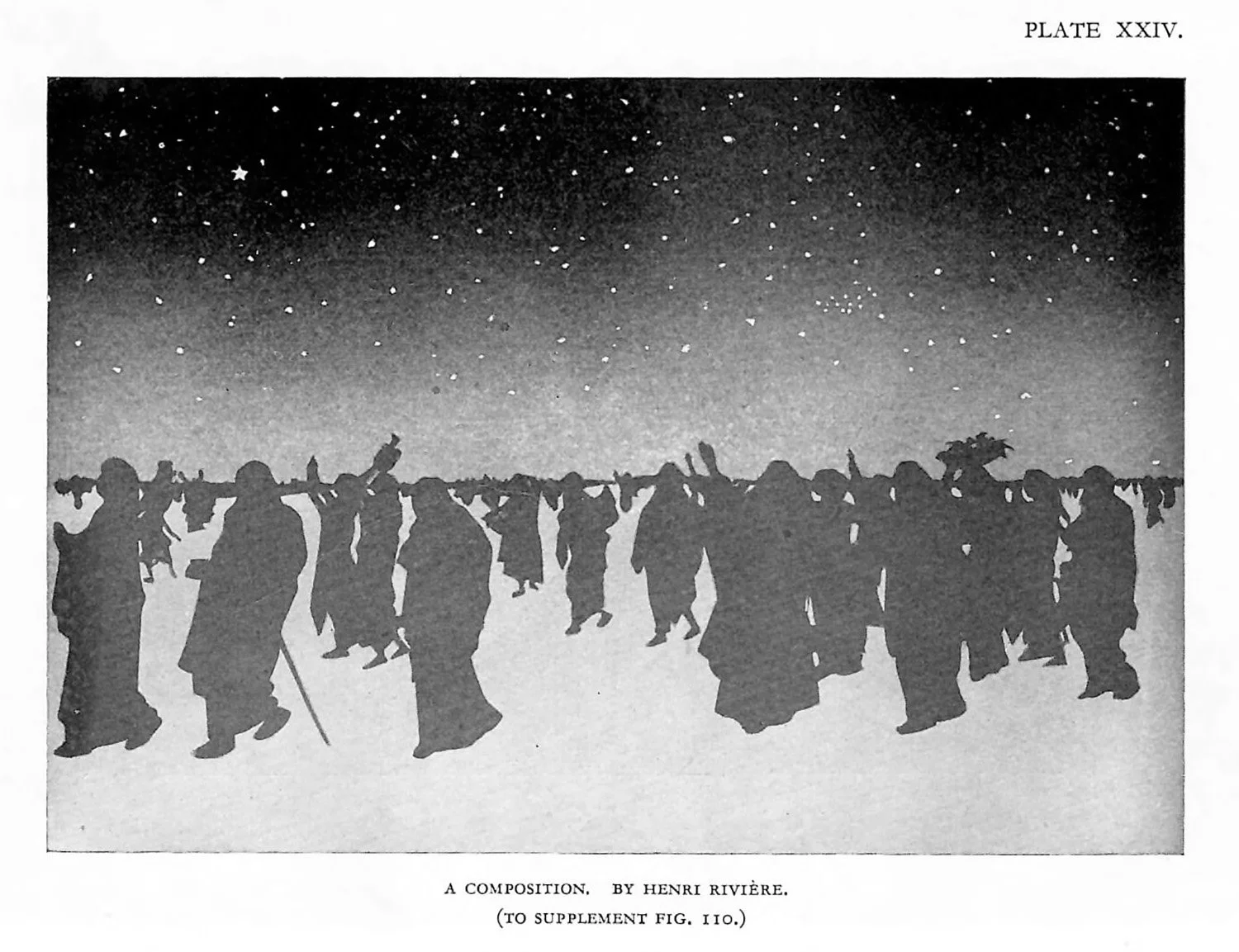

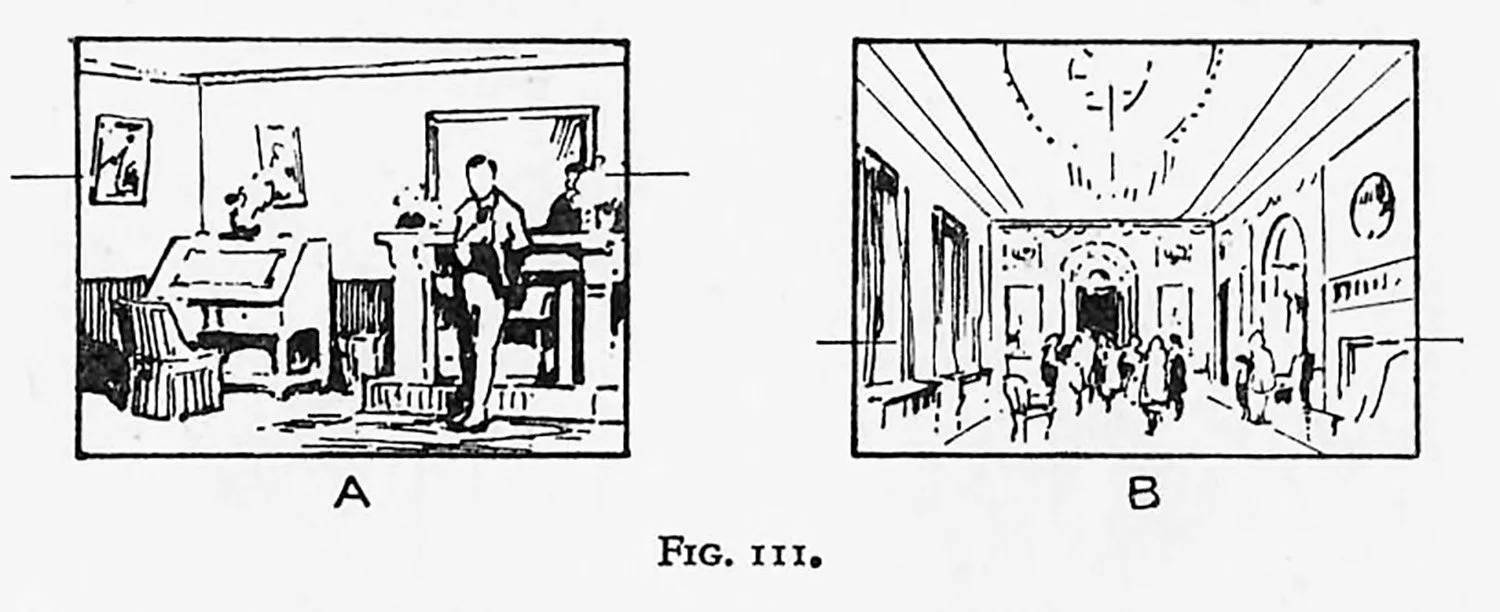

We now retutn to our question of perspective scale. It is well known that when the spectator is standing up and figures are to be tepresented also upright on the same level ground we find that the heads remain level, although the feet may vary in vertical position. The adjoining diagram A in Fig. 110 illustrates this perspective law. Under this condition a crowd of people on a level surface will also conform to such a law, the slight differences in height being allowed for. Diagram B shows this. In composition we must attempt to keep this knowledge in a secondary position. Take the contours 1 and 2 in Diagram C and Plate XXIV. Their position and variety should be given the first attention. In the next two diagrams (A and B in Fig. 111) the spectator is level with the person shown, but the room is high in one case and low in the other. Both diagrams ate accurate as far as perspective is concerned, but the real problem for the student of composition is not the accuracy of the scheme (that is easily ascertained), but whether or not the figure is the correct size for the idea we wish to express. Does it occupy as much of the picture as we intend? When this has been decided perspective can enter into the scheme.

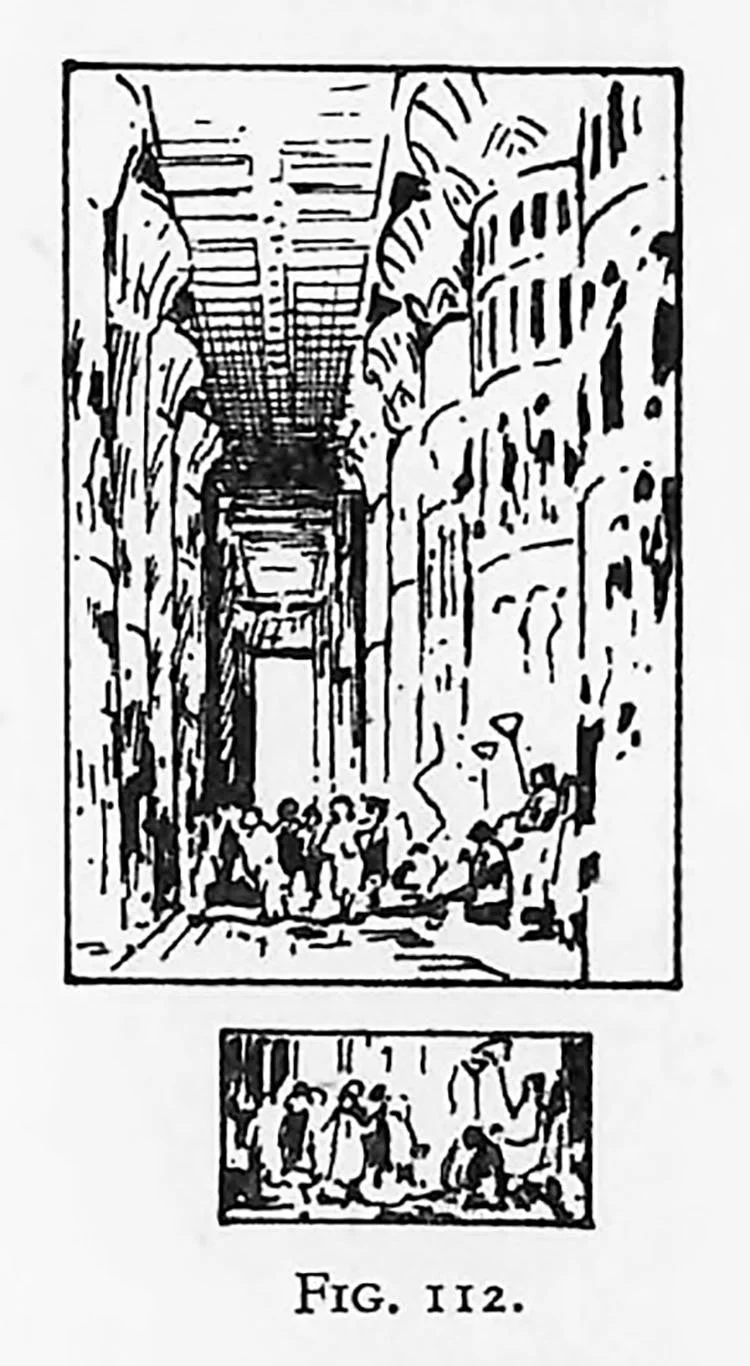

The writer remembers, many yeats ago, an occasion when students were requested to bring a composition for the criticism of the master. The subject that had been given was “Moses before Pharaoh.” One student who was most efficient in matters relating to perspective handed in a picture something like the accompanying diagram, in which it will be seen that the architectural features had been given undue importance (Fig. 112). The master silently cut out the portion shown in the adjoining sketch, and having pinned this small piece up he discussed it as a new composition.

If we witnessed a subject where the emotions were strained almost to their breaking-point, we should undoubtedly be watching intently the figures themselves to see the outcome of the challenge; they would be given our undivided attention. The cinema-man would give a “close-up.” If the subject had been “A Ceremony in the Temple” the proportions of the composition referred to above would have been more excusable.

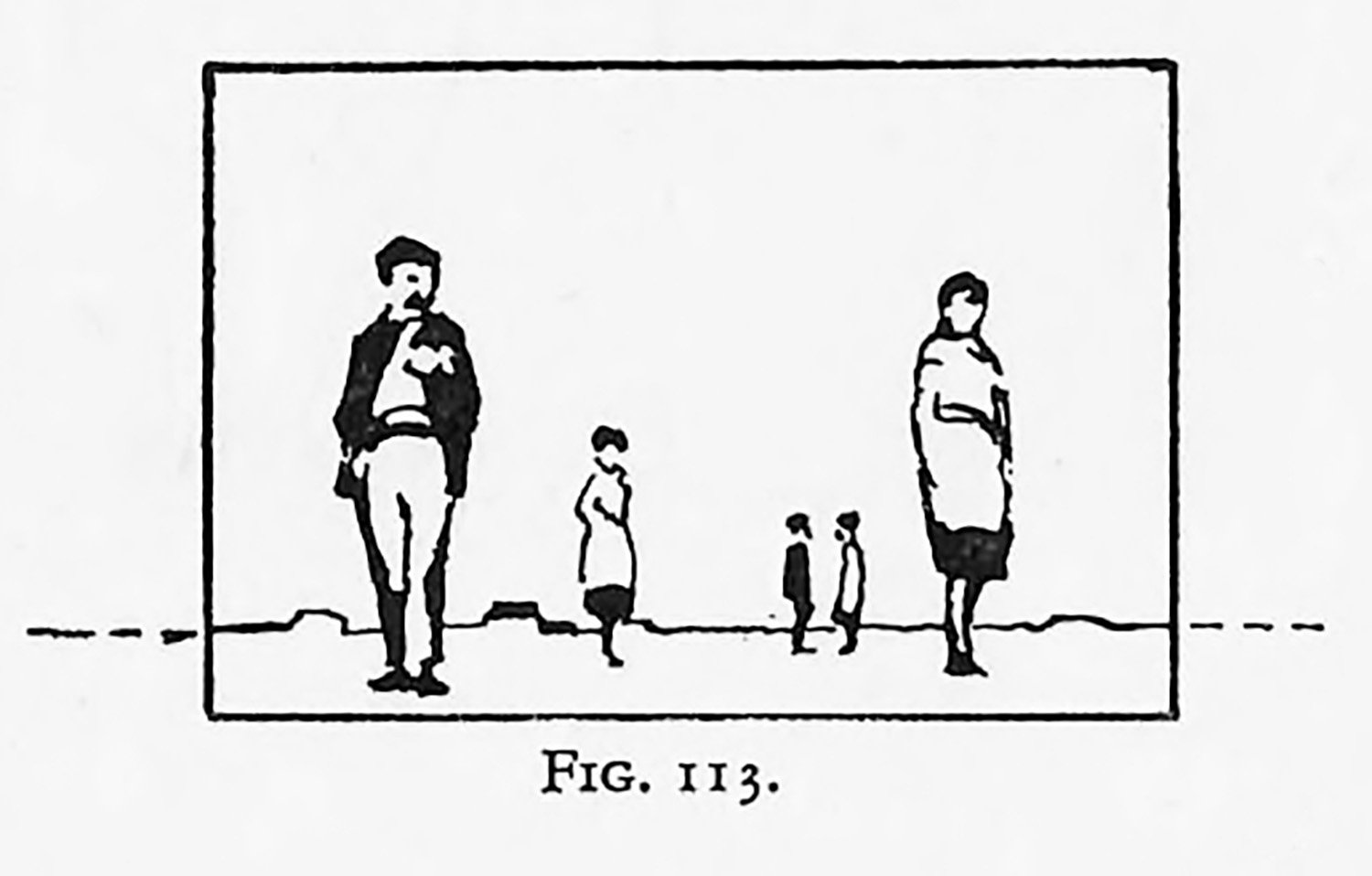

Having acquired the habit of compelling perspective to serve our turn, let us turn to Fig. 113.

This is a case whete the spectator is assumed to be on a very low eye-level, such as lying flat on the ground, his eyes level with the line X-Y. An arrangement of this character makes the figures loom up like giants. This is a scheme that has been given a lot of attention in recent times, especially in commercial art.

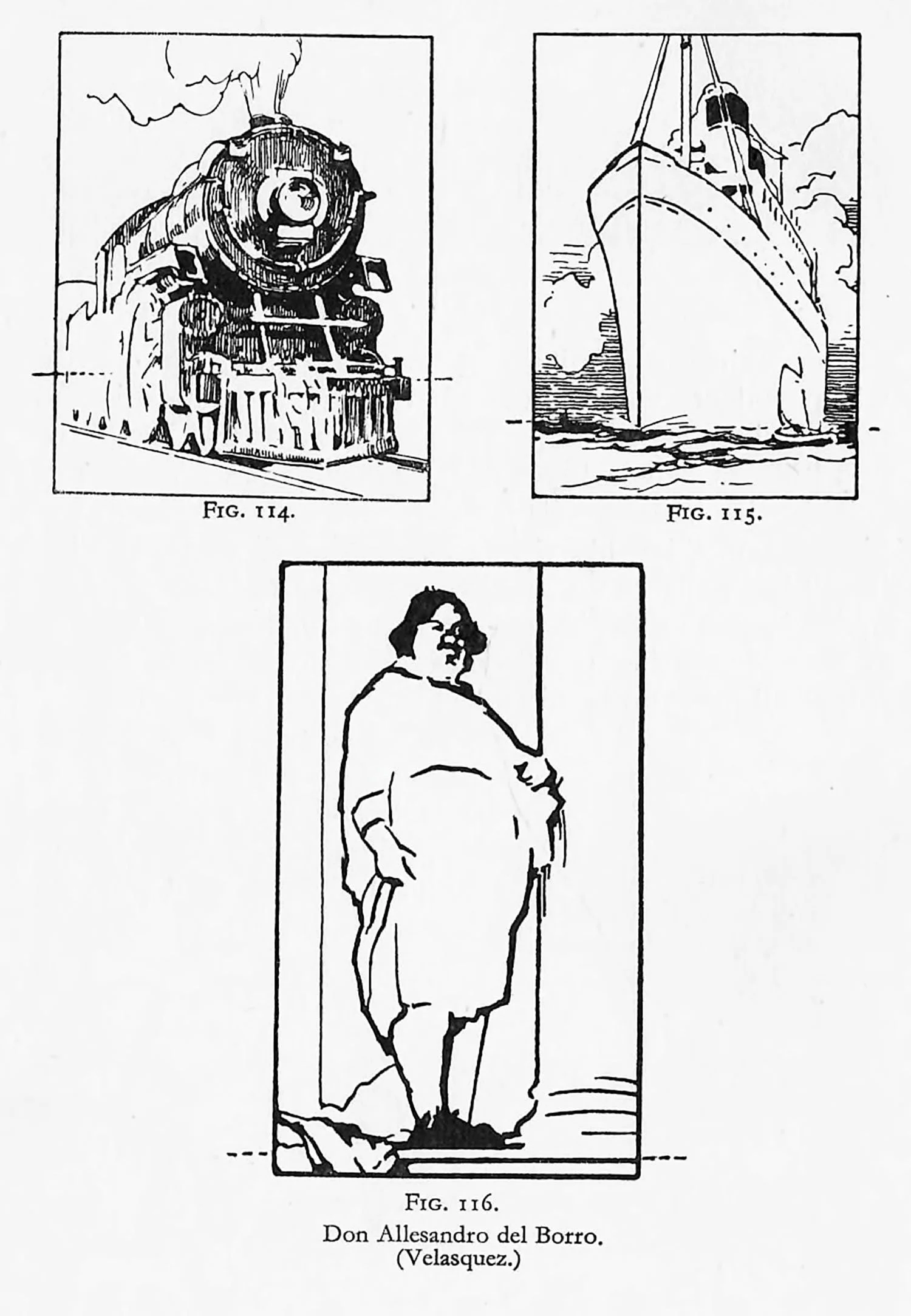

It is common in playbills and posters, especially the posters advertising liners and railways. The three sketches shown in Figs. 114, 115 and 116 are sufficient to show how the gigantic can be suggested by this means, but here again discretion must be observed. A portrait done in this manner is apt to suggest unnecessary egotism—a lofty but ludicrous superiority, amusing enough as a playbill, but inclined to be unjust to an individual. Velasquez used this method in his well-known Don Allesandro del Borro, where he painted a great braggart stepping upon his enemy’s flag (Fig. 116).