Chapter XI.

Rectangles and Their Subdivisions

ALTHOUGH environment and the nature of materials, have been powerful influences in the design of many things, yet, when all conditions of use and material have been allowed for, there is still required an added touch of nice judgment—the hall-mark of individual taste. We feel that the craftsman has, critically or whimsically, adjusted the object to his aesthetic needs long after utilitarian conditions have been fulfilled. The size of a rectangular doorway in relation to the building, the proportion of a tower to the rest of a cathedral, or the subdivisions of a gate or a window must often cause no little esthetic consideration in the minds of the designers responsible for such work.

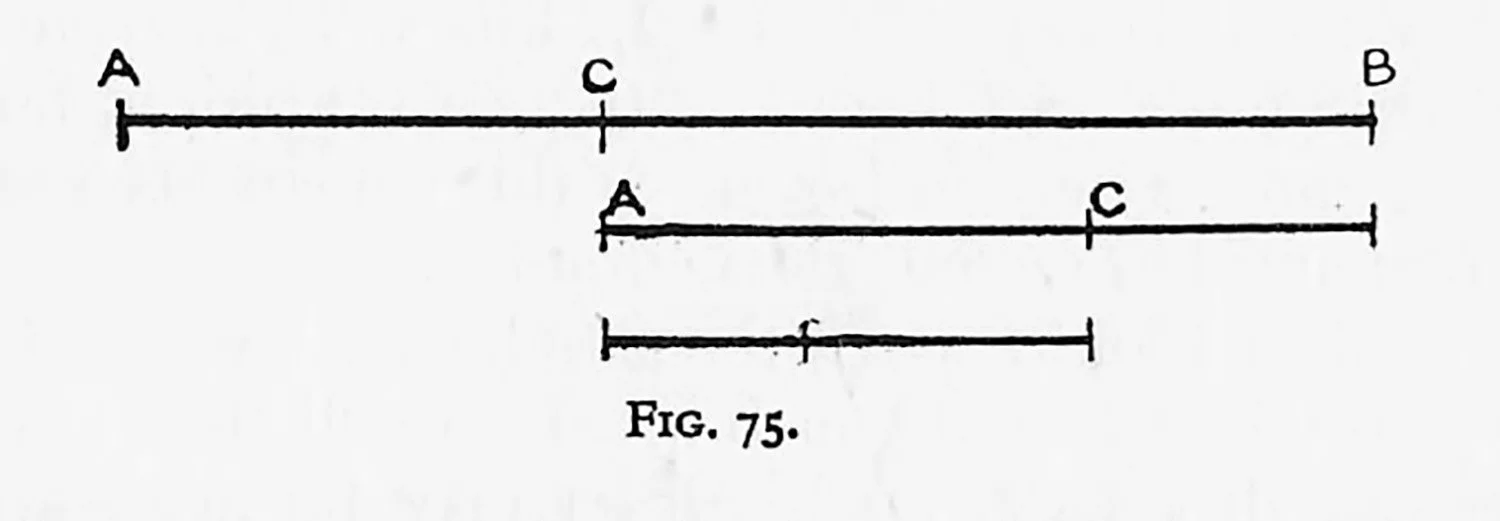

Pictures and decorations being designs on a plane surface ate more concerned with proportions of line and two-dimensional areas and their relations than with cubic content. Such works, being valueless from the utilitarian point of view, consequently possess unlimited licence in proportion. Even then a common consent as to agreeableness or otherwise of certain proportions is felt. Pythagoras was reported to have held a rod at its ends, horizontally, and asked his friends to put a mark on it in a position that gave the feeling of a satisfactory yet unequal proportion. He found, as we shall find if we experiment, a striking unanimity of opinion. The diagram, Fig. 75, shows the proportion. It seems as if we place C in such a position in order to avoid the obvious third on the left and the uncertain half on the right. Pythagoras found that by placing the length A-C on the remainder C-B the proportion remained as before. The short division, when placed on the longer, yields the same proportions to infinity. How such apparently irreconcilable proportions in line became reconciled eventually in area, how the irrational became systematized, is found in the early history of mathematics. It is certain that this proportion was used centuries before the Pythagorean incident, though probably intuitively. Yet from that time it became an intellectual concept, and after many disappearances and discoveries Kepler brought it to prominence by writing an enthusiastic dissertation on “the golden measure.”

Three-legged compasses have been devised to secure this golden measure between two points. In modern times researches into the animal and plant world have revealed the proportion to be a natural ratio. In his work On the Interpretation of the Phenomena of Phyllotaxis, Dr. A. H. Chuich, of Oxford, has written at length on such ratios.

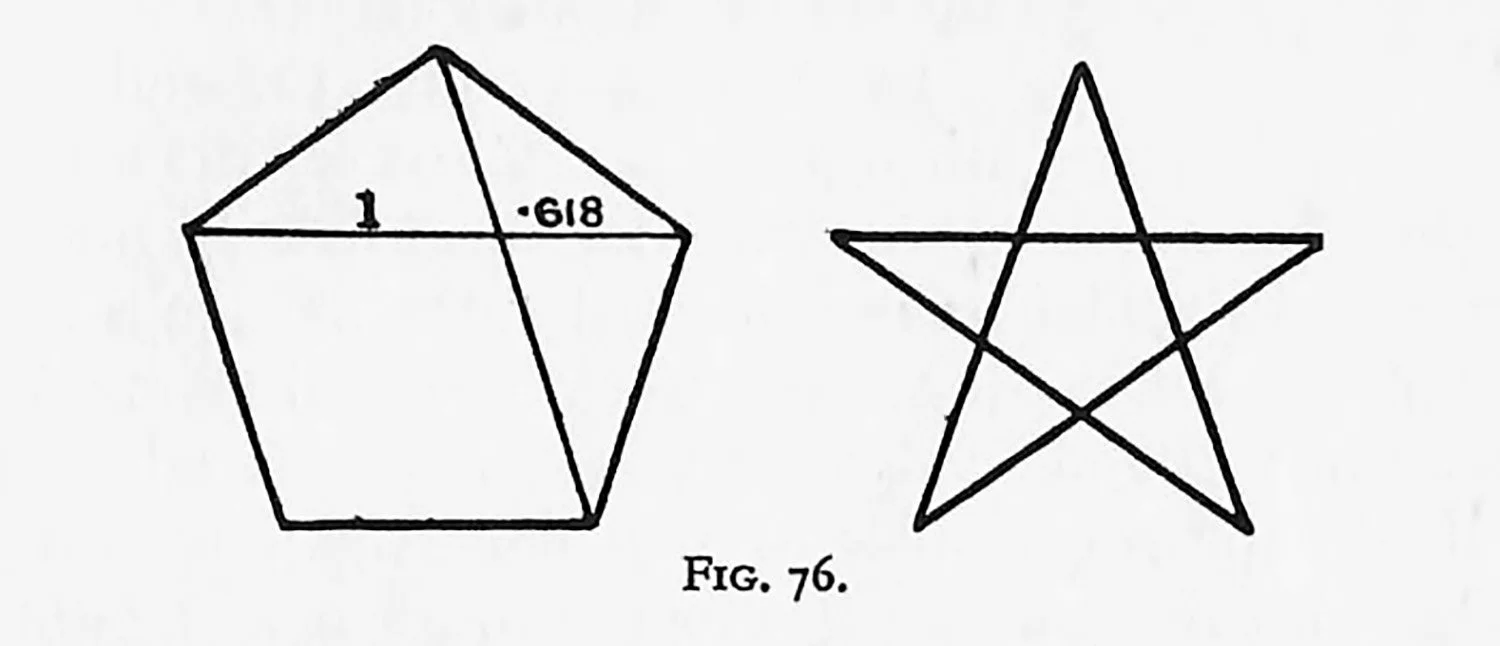

The intersection of two diagonals of a pentagon (Fig. 76) gives the ratio geometrically, and some have supposed that the five-pointed star which the disciples of Pythagoras wore was a symbol of their knowledge of such matters. Quite apart from speculation, such a division, the ratio of 1 to 1.618 approximately, is to be found as one of the great proportions in almost every picture.

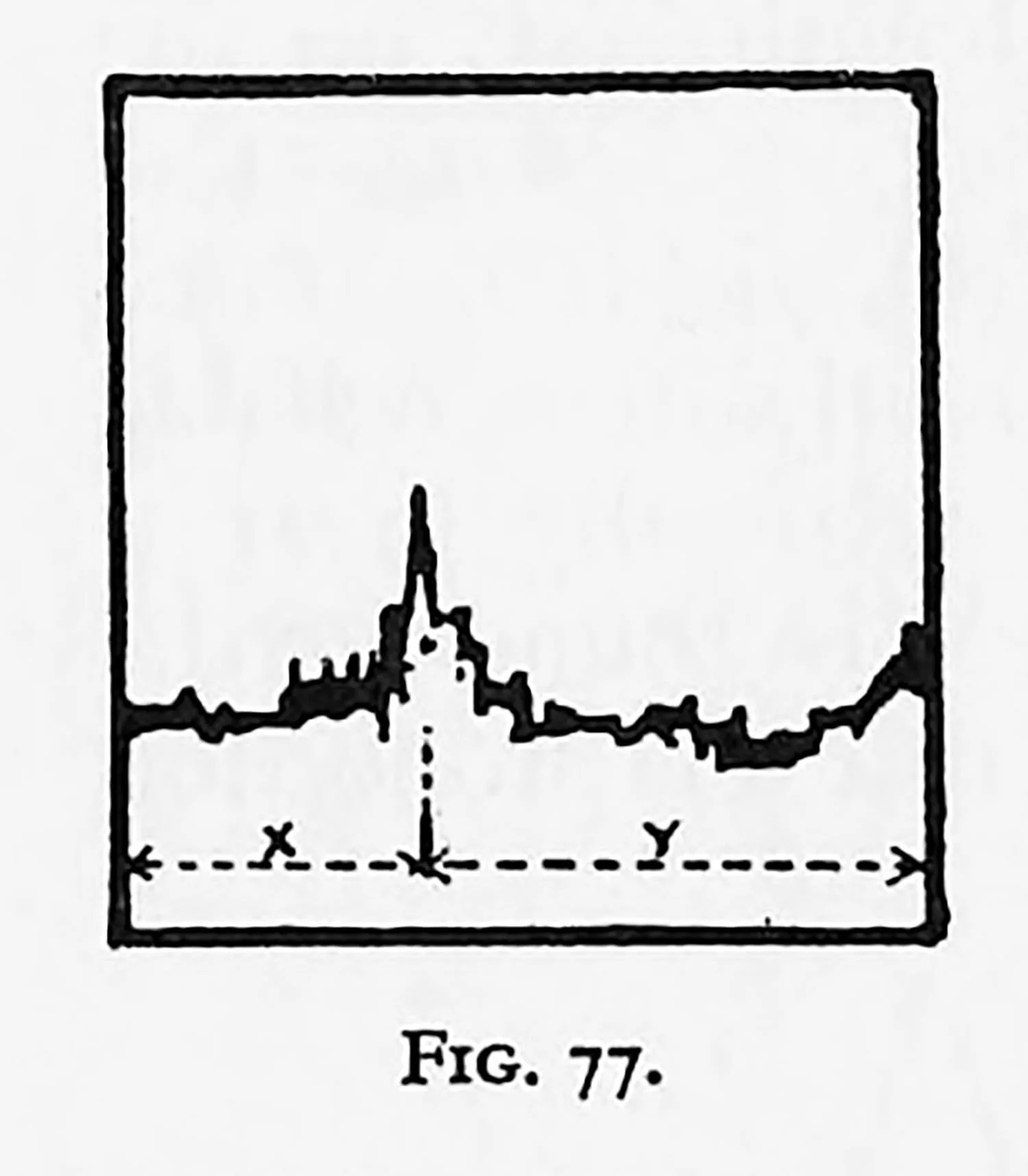

A contour is given to show how it may be used (Fig. 77).

Now that the application of “irreconcilable” proportions has been discussed it will be necessary to make a few geometric statements regarding the placing of rectangles within each other or by the side of each other, whilst the rectangles agree proportionally.

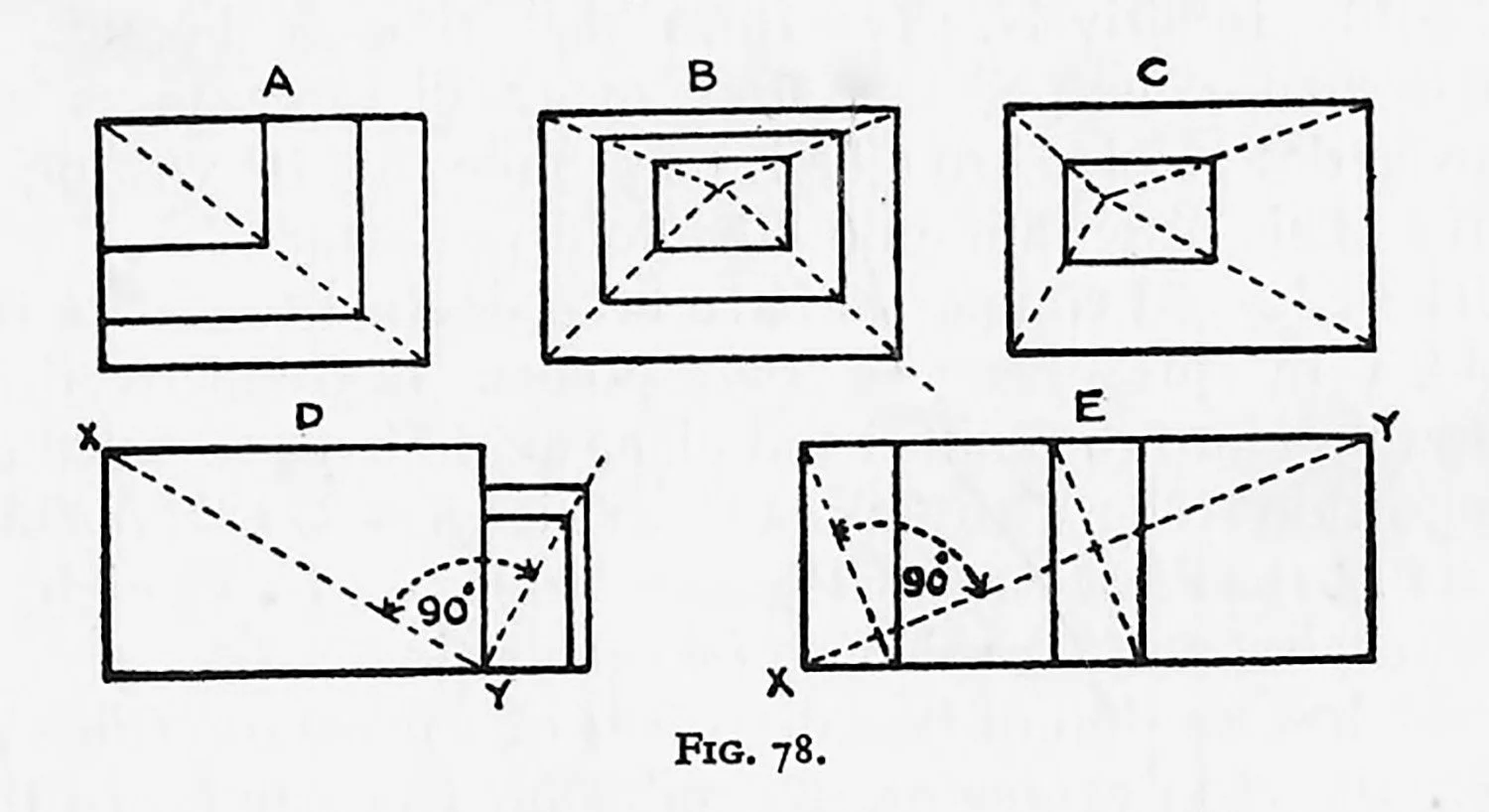

hus, in the diagrams A, B, and C in Fig. 78, by means of the constructions shown by the dotted lines, we obviously make the inner and outer rectangles similar in proportion.

In the diagrams D and E the diagonals X, Y were drawn and a straight line drawn at 90° to the diagonal. If lines were now drawn parallel to the original sides we again produce rectangles equal in proportion to the original rectangle.

Diagrams D and E also turn over the rectangle—that is, we obtain the short sides of the new rectangles on a line parallel with the longer sides or the original rectangle.

It is true that such proportions could be obtained arithmetically, and it may be asked, “What has all this geometry to do with composition?” Consistent rectangles, or rectangles of similar proportions, have always been considered a unifying factor in a composition, for we can, by this means, gain variety of area with unity of proportions.

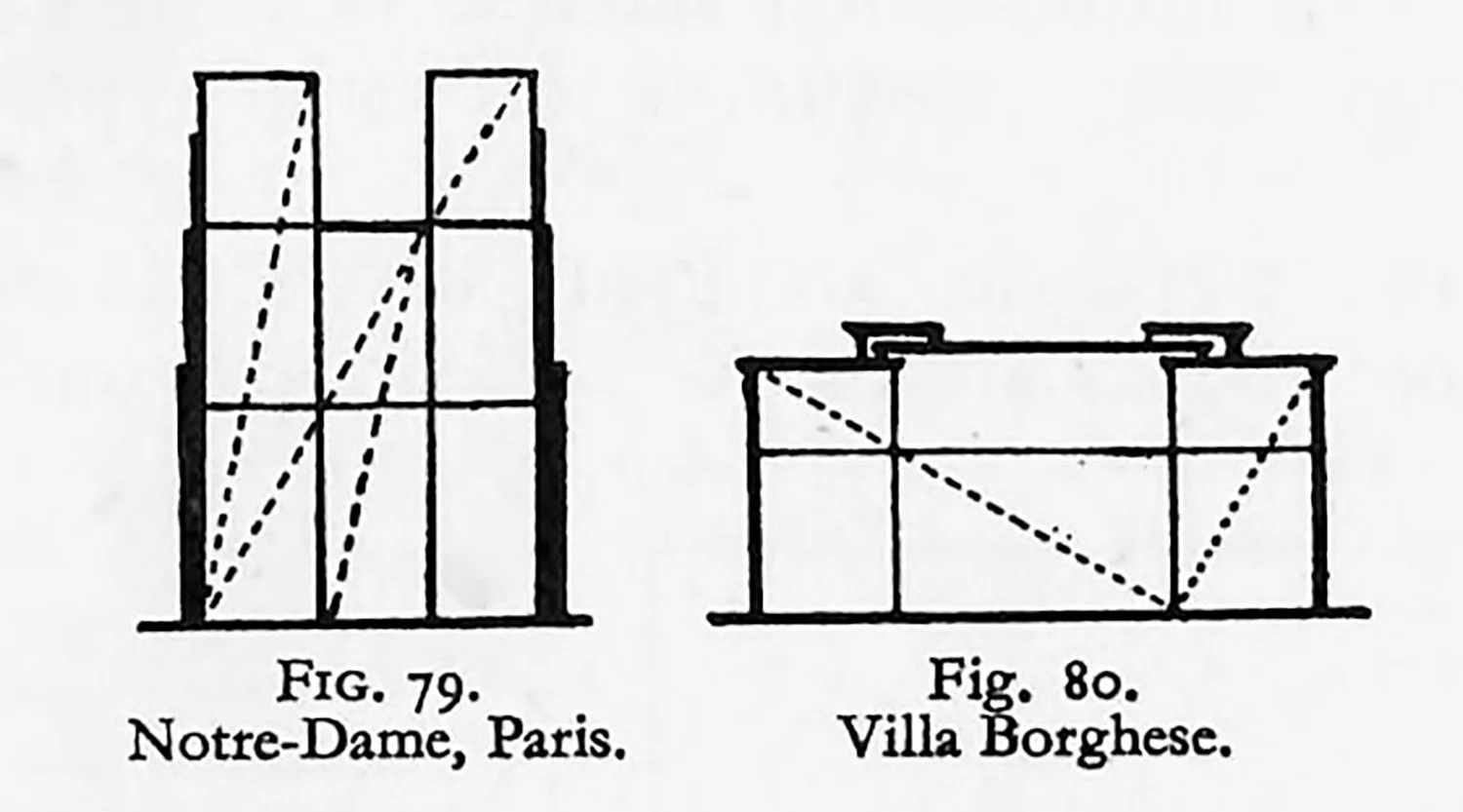

A great deal has been written in works on architectural composition regarding consistent rectangles and how their use makes for unity. Two examples, adapted from J. B. Robinson’s Architectural Composition (published by Batsford), are given in Figs. 79 and 80.

The question of what proportion constitutes a satisfactory rectangle is still remaining unanswered. In this connection great credit is due to the researches of the late Mr. Jay Hambridge, who was granted a research fellowship at one of the American universities. In his works, The Greek Vase, and his periodical, Dynamic Symmetry, he published a very convincing account of the efficiency of square-root rectangles and how such rectangles could be used to determine the design and good proportion of ancient and modern vases, ornaments and buildings. His written work, mathematical in character, as such research must be, was concerned with showing the superiority of square-root rectangles over the ordinary static or obviously dimensional rectangle. Subtlety of proportion in its mathematical relation was the object of his research.

The books referred to should prove interesting to the student with a mathematical interest in design, for they analyse many choice specimens of antique pottery and jewellery.

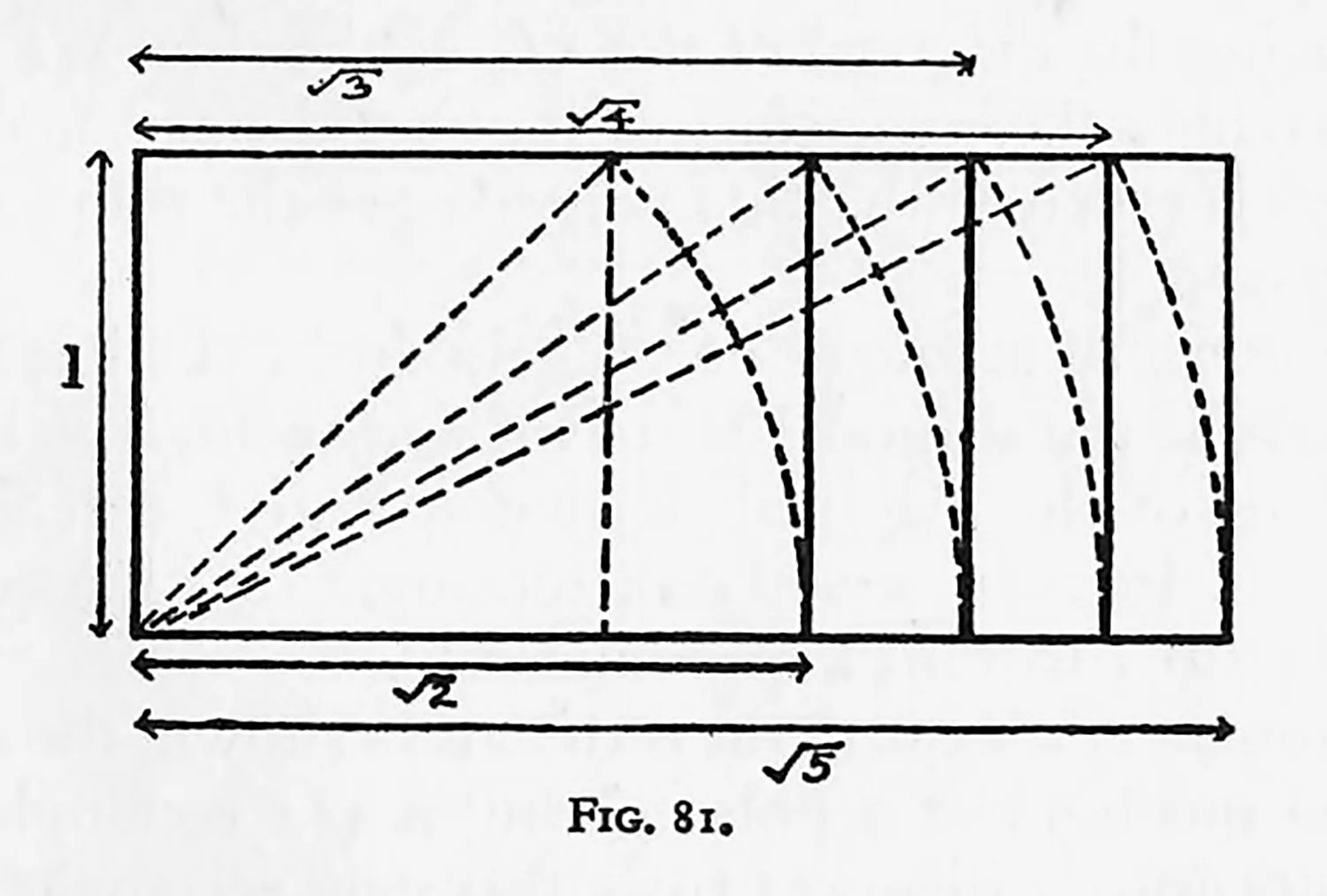

Square-root rectangles are easily described as follows: Starting from the square or “unity,” the diagonal is taken as the long side, as shown in Fig. 81. Such a rectangle is called a √2 rectangle, for the length of the long side would, if used as the side of a square, be twice the area of the original square. The same idea holds good if we use the diagonal of the √2 rectangle as the side, and we obtain a √3 rectangle, again using the diagonal of the √3 as the side. We derive a √4 rectangle (i.e. two squares long) and once again if the diagonal is taken as the side we arrive at the proportions of a √5 rectangle.

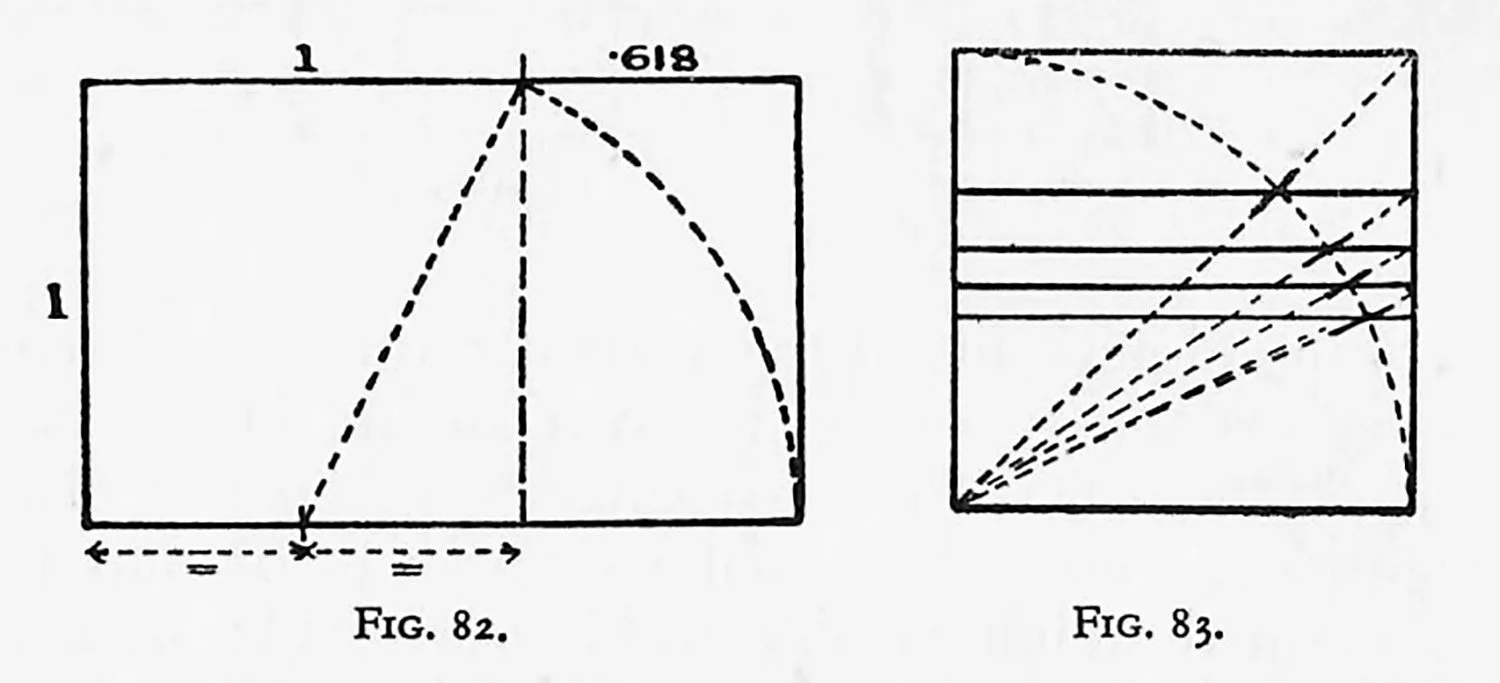

Starting with a square once again and bisecting the base as shown, if the diagonal is drawn and, using the bisection as a pivot of the diagonal, is swung round, extending the base, as in Fig. 82, we have a rectangle that illustrates the natural ratio 1 to 1.618 approximately.

If a square and a quadrant is drawn as shown, the diagonal cuts the quadrant at a point giving a √2 rectangle on the lower portion; a diagonal from this new rectangle cuts the quadrant so that a √3 rectangle is formed below, √4 and √5 similarly follow. The resulting line divisions of √2, √3, and √5 are undoubtedly subtle, and, in consequence, useful. Another point in favour of such rectangles is the subtle proportion of the “remaining” shapes after a square-root division has been made. Fig. 83 shows this construction.

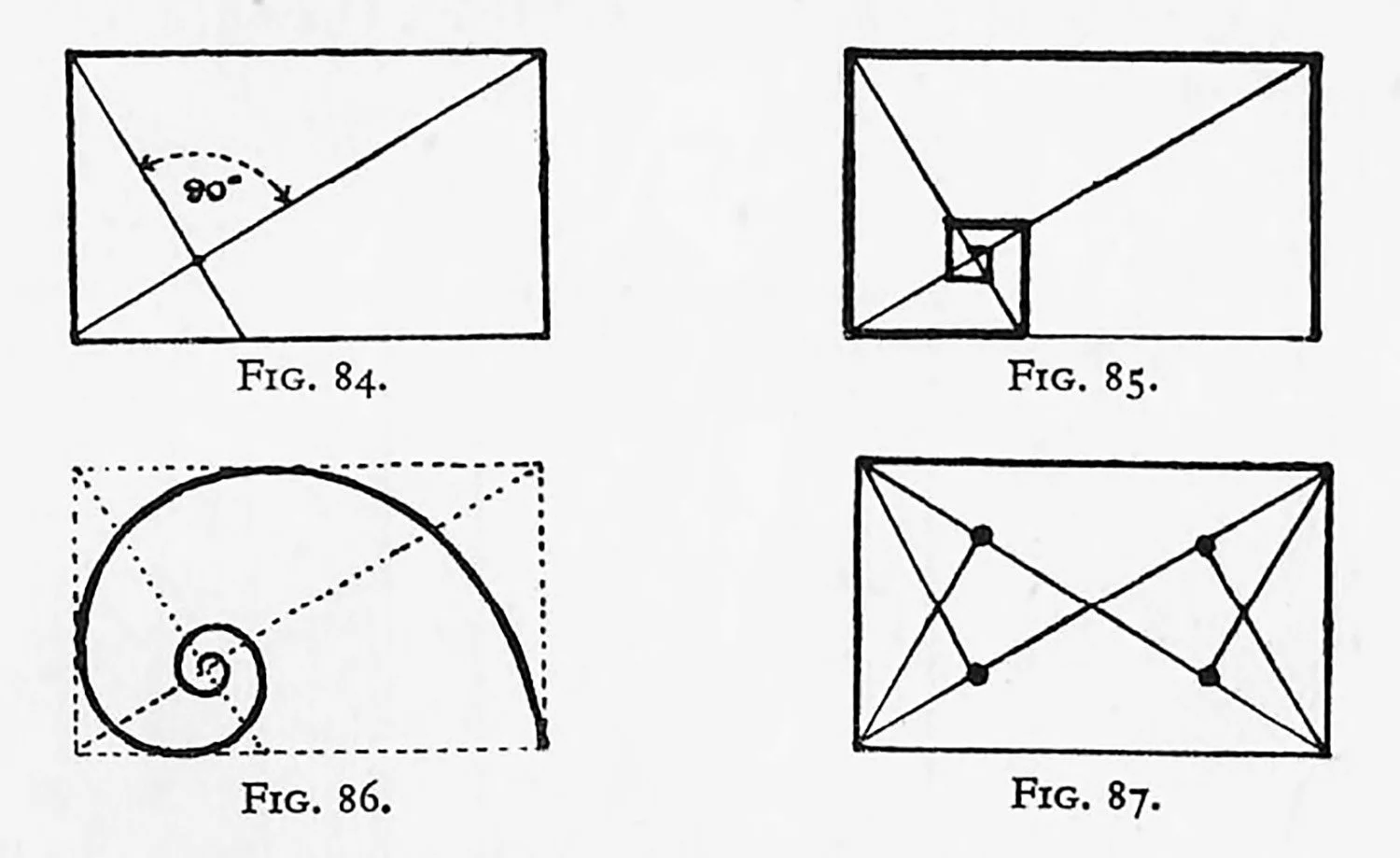

In all rectangles, whether “dynamic” or not, can be found subtle positions that might be termed “eyes.”

A rectangle with a diagonal and a line from an adjacent cornet cutting the diagonal at right angles, as shown in our “reciprocal rectangle problems” D and E, is given in Fig. 84. The point where the diagonal is intersected can be called the “eye” and lines parallel with the sides are drawn, which approach, but “theoretically” never teach, such a point. Such a scheme is illustrated in the shell, where the spiral line has been substituted for the cornered line (Figs. 85 and 86).

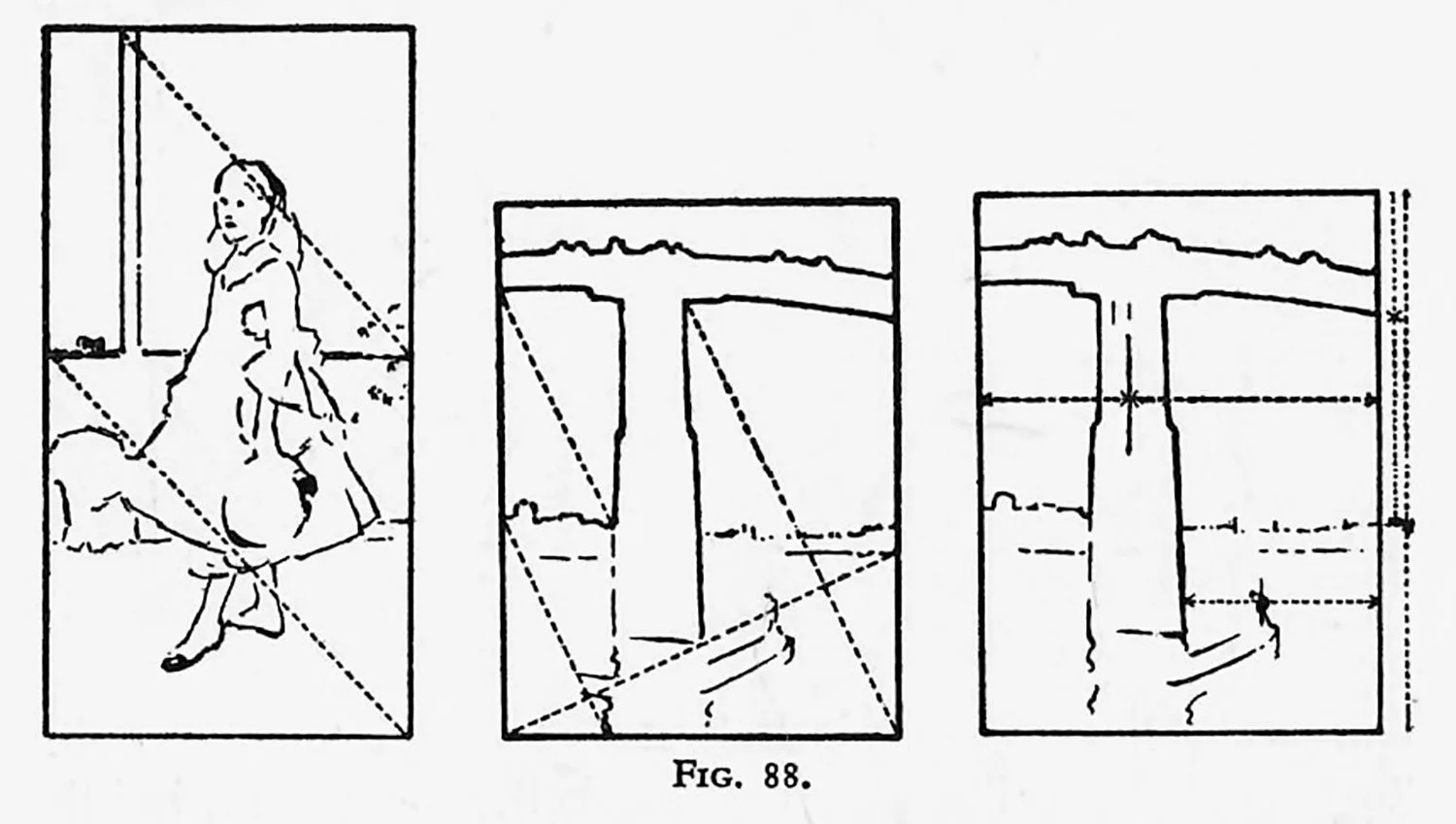

Evety rectangle contains four “eyes” (Fig. 87), and it should be clear that rectangles with rectangular divisions will contain an additional number of such “eyes.” The analysis of many pictures would prove that the foci or central point of interest of forms, tones, and colours are often placed on one of these spots or “eyes.”

Most artists, however, rely upon their critical feelings in questions relating to satisfactory proportions, although it is just conceivable that a master might arise who, possessing both mathematical and esthetic qualifications, would proceed to design a miracle of subtle proportion by means of geometrical constructions.

In designs where rectangles are clearly defined such as we find in architecture and furniture, mathematical certainty derived from aesthetic experience is obviously of great value. Rectangles in their pute state, however, ate rarely used in pictorial expression, and so we ate compelled to sense or feel intuitively when the divisions and proportions give satisfaction. Research on the lines indicated may help to train or stimulate our intuition, and it is clear that when rectangles are to be divided we must aim at subtlety. Obvious fractional divisions, such as one-half, one-third, or one-quarter, soon tend to become tiresome. They are found out and quickly cease to interest. When rectangles possessing similar proportions occur within a picture they reiterate and in consequence give coherence and unity to a design.

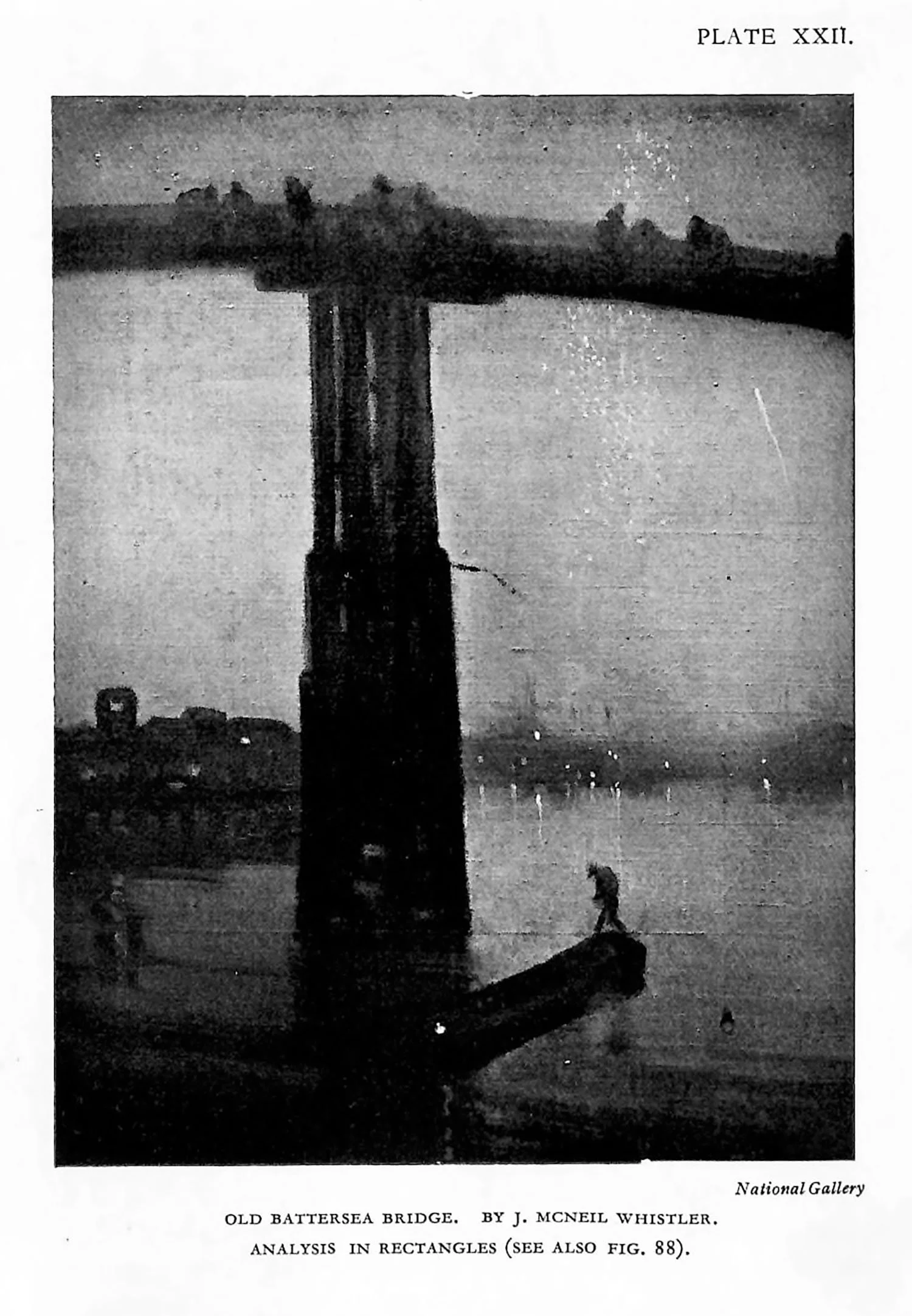

he student’s attention is drawn to such similarity of proportion in the rectangles of Whistler’s Battersea Bridge and his Miss Alexander, shown in Plate XXII and Fig. 88. Many other examples could be shown to illustrate this reiteration.

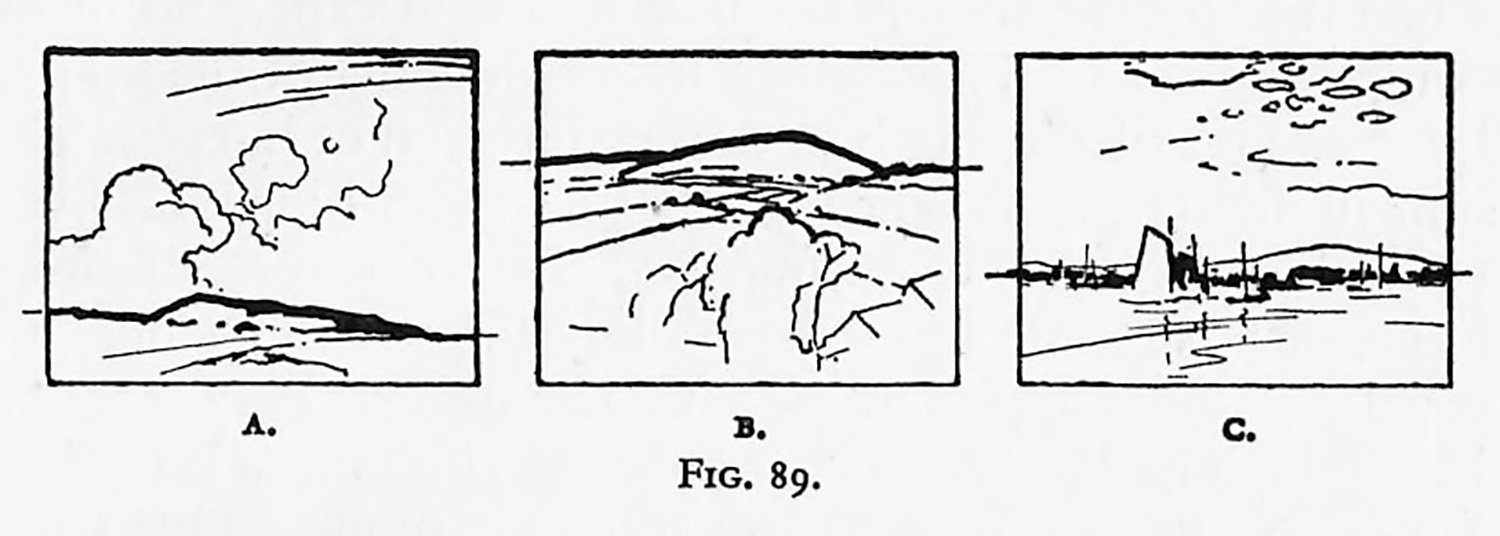

Then comes the question of scale in such enclosed rectangles. Scale has already been insisted upon as a rhythmic law in the discussion on tone, yet it may not be out of place, in a consideration of relative rectangles, if it is again pointed out that complete and lasting satisfaction arises only when the scale of rectangular areas descends by “nice” stages, and perhaps this remark implies that we are intuitively conscious of ratios. In practice it is an excellent plan to pin up in a place where we can sit and occasionally look at it any sketch in which a scale of proportionate rectangles occurs. Sometimes out somewhat indirect observation will locate an offending proportion when perhaps our actual direct concentration has failed. This method may perhaps be personal, but it is worth trying when any compositional difficulty occurs. It may appear out of place in a book on composition to advise the student to “sleep on it,” but it is common experience that a pictorial scheme begun with great enthusiasm does not always live up to its promise the next day. We discover, perhaps, that the outside or containing shape does not quite suit the enclosed design; it may appear to be too long to give us the necessary expansion upwards, or it may be that the containing shape is nearly square and is inclined to bother one. If it really looks square our doubts are resolved, but if it looks a doubtful square we speculate on which are the longer sides, and our attention has been diverted from enjoying the contained design. Apart from relative proportions, the question arises of giving each subdivided rectangle its proper form-content. This will be understood better if we take a rectangle and draw across it a division of pictorial form, with a suggestion of land and sky.

Diagrams A, B and C in Fig. 89 show three positions of this division. Apart from the question of exact proportion of sky to land, we must determine which section is to contain our chief interest. Diagram A suggests a possible proportion if the sky is to be the subject of our expression. The largest atea should, if possible, be occupied by the chief interest. The contour placed as in Diagram B will be advisable if the town or the area below the contour is our real motive.

Diagram C might be a possible position for a line of interesting objects around the contour itself, the remaining areas being sky and water. There is always a danger in keeping the interest confined to the smaller areas.

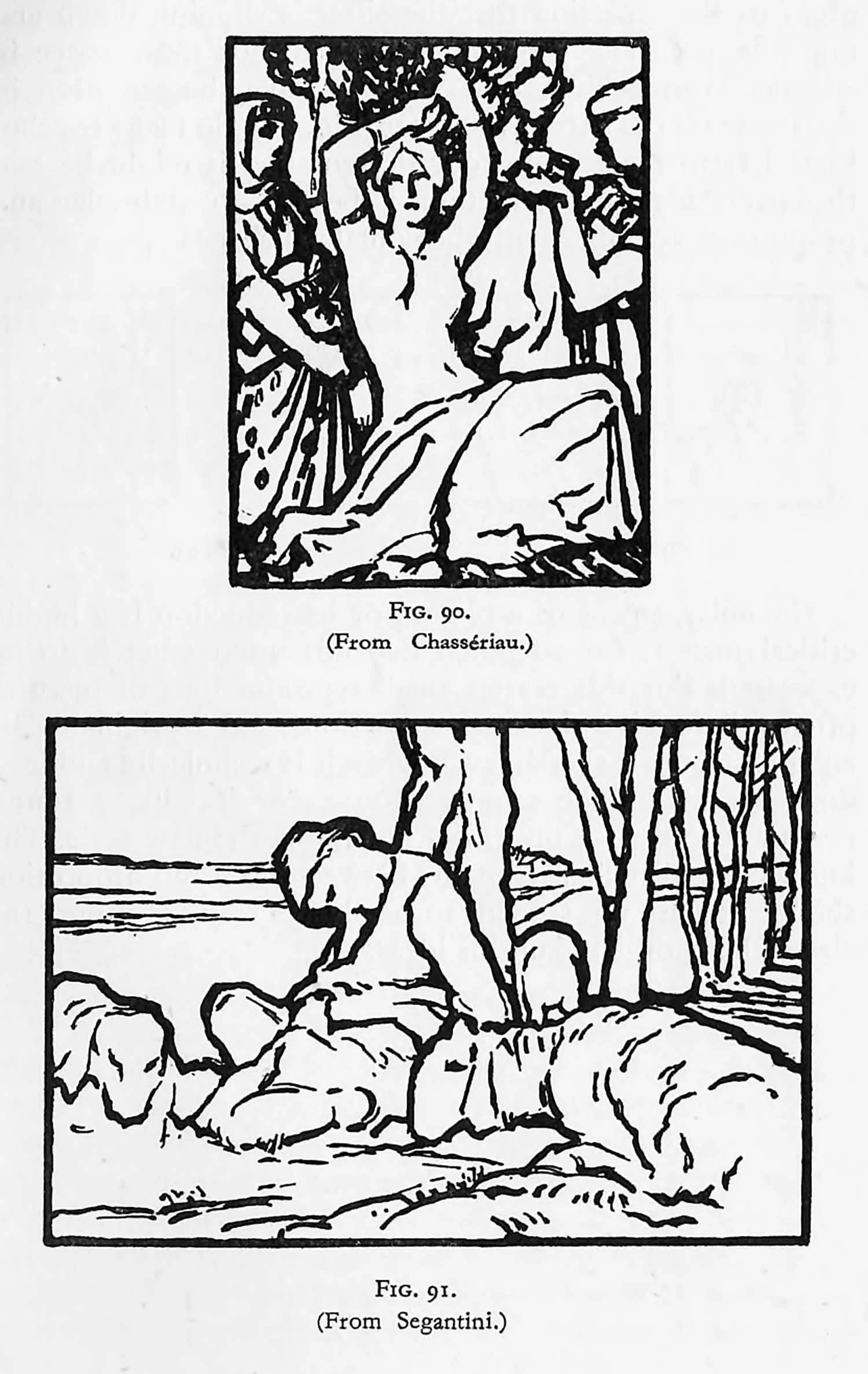

If the chief forms occupy the larger areas in as bold a manner as possible, we might avoid having our work described by that uncomfortable and somewhat derisive term “small in design.” A similar difficulty frequently arises when the student attempts figures in a landscape, and many compositions have been ruined by the drawing of the figures large and detailed enough to cause confusion of interest. The human figure, even when small in composition area, can easily become too interesting, and the landscape, although large, degenerates into mere padding. Figures in a landscape usually become important because the student has forgotten his initial impulse. The great landscape composers kept their figures small—sometimes mere spots of colour—with a few suggestive forms to give vitality.

When the student finds the human interest becoming too strong in a landscape, a piece containing the figures should be cut out and considered on its merits as a figure composition. It could then be re-designed, making the figures reasonably occupy the whole space. Figs. 90 and 91 are examples of bold design.

A travelling collection of drawings and paintings by Viennese children attracted considerable attention in this country a few yeats ago. It would seem that in certain exercises the only stipulation was that the figure should neatly touch the top and bottom of the space to be filled. This condition made the figures important in scale, and the remaining shapes were easily filled with apples, flowers, baskets and other accessories that were in keeping with the figures. This, of course, gives to such figures their greatest possible area for a containing rectangle, but there is no finality in such a rule. It is just as likely to cramp the movement of a figure or to suggest a jack-in-the-box ready to expand if the space or edge of the frame wete to give way.

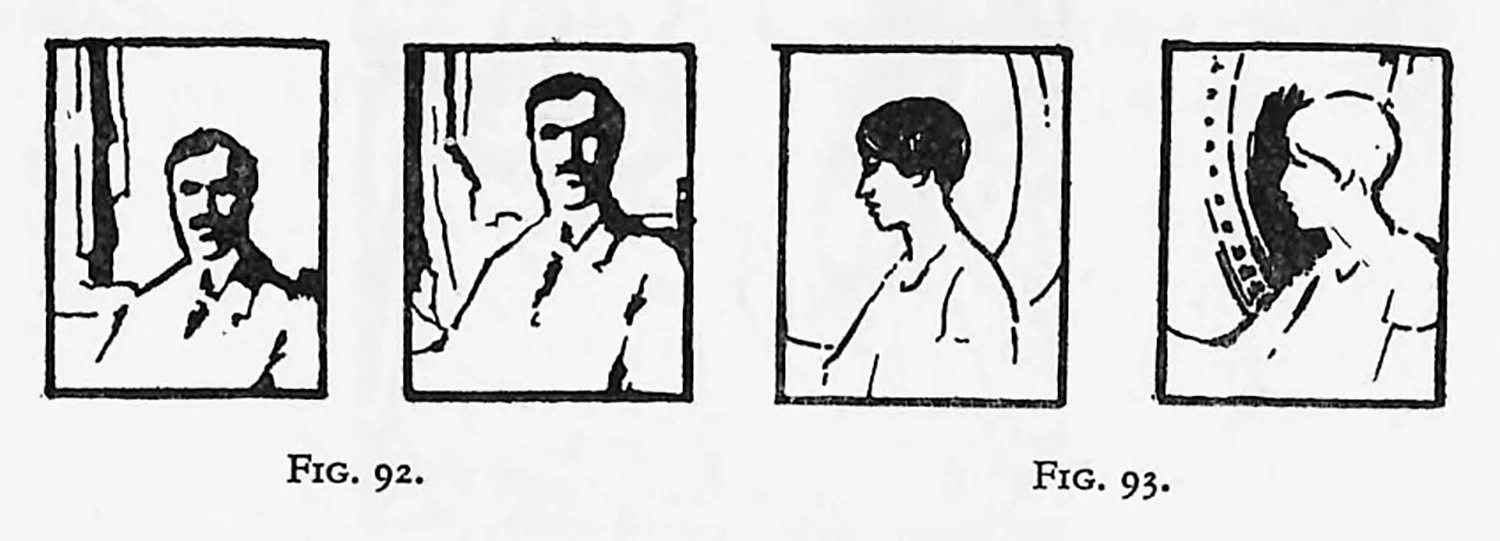

In the design of a portrait, tying the head to the top edge is, perhaps, better than having it a little too low, which gives us the sensation that the sitter is slipping down and out (Fig 92). The profile usually demands mote space in advance than behind, otherwise we give the sensation of departure on the part of the sitter (Fig. 93). So many psychological factors enter into our designs that it might be said that every idea, every picture, is best at a certain size and proportion, together with the contained shapes.

The enlargement of a pictute or its reduction is a highly critical matter, for so much depends upon what is to be expressed. For this reason small reproductions of pictures often fail to give the same sensation as the original. The enlargement of a sketch, even when it is technically faultless, does not evoke the same response, for it will be found necessary to treat it on its own merits at the new scale. The knowledge of such a sympathy between scale and proportion should prepare the student to be always ready to adjust the size of his works to suit his ideas.