Chapter X.

LINE-DIRECTION (Continued)

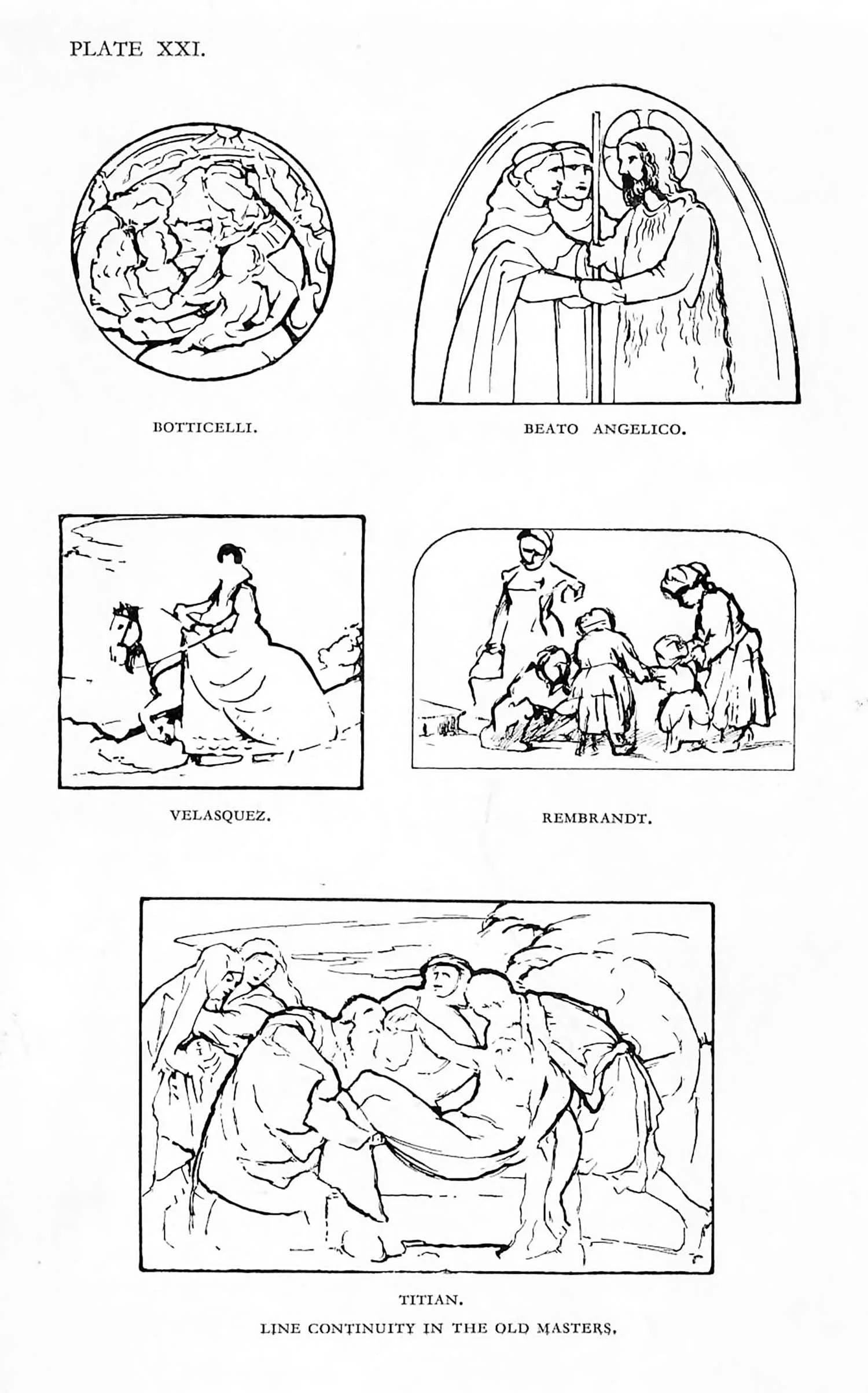

THE relation of the straight to the curved and what we think to be a proper balance between them in a work of art depends largely upon out attitude towards life and things generally. Both the age and the environment in which an artist lives help to determine such a balance, and the art student who has studied the so-called historical periods should be aware of a continual alteration or readjustment of such conditions.

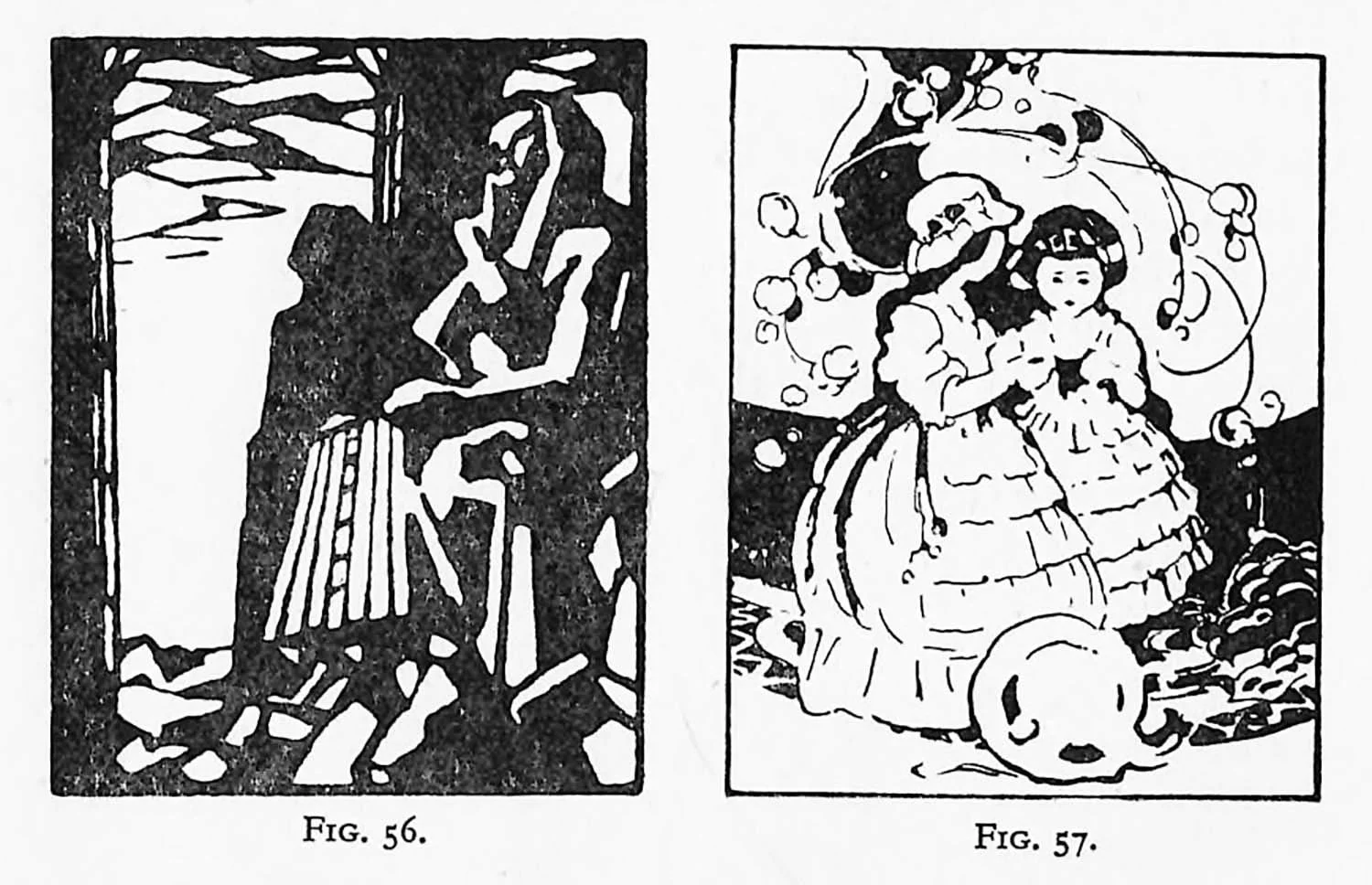

Most students who give a bias of straightness to their designs usually do so from conviction, for they like the severity such lines imply, but a number of other students give a bias of curvature because the graceful, and sometimes the sweet and cloying, appeals to them (see Figs. 56 and 57).

If either bias can be considered a defect it can only be corrected by a continued observation of life itself. In composition there can be no doubt that straight structural lines and squareness give the feeling of strength and security, but when their use is carried to extremes they convey sensations of harshness and crudity. Again, curvature may suggest vitality and grace, but when used to an excessive degree it gives a restless insecurity and weakness. The consideration of lines that contradict and lines that agree or relate is closely allied to such a question. If we observe plant-growth we recognize the growing-out or evolutionary character of the forms. The lines radiate, and such lines are obviously related. The value of radiation in composition has been dealt with, in the chapter on Perspective.

It is in dealing with the lines that contradict or oppose in the directional sense that sometimes a call has to be made for a reconciliation. To effect this, links or transitional lines are used. The tree trunk is a standard example of how vertical lines meeting the horizontal ate often unified by the transitional lines of the roots (Fig. 58).

The neck of a human being in its relations to the head and trunk shows lines and planes that are transitional in character. We have only to spread our fingers to notice the interesting manner in which one line of a finger relates at the junction to the sides of the next finger.

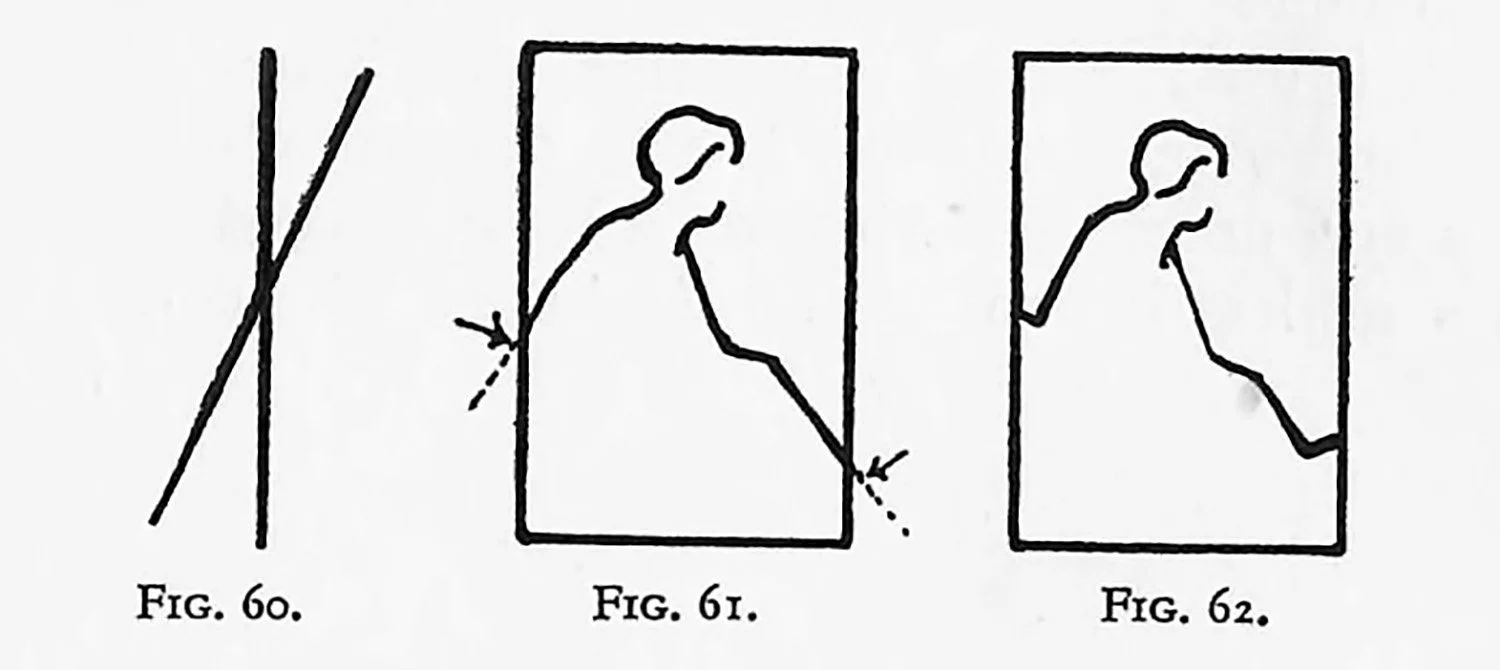

It should be observed that the lines that offend most in a composition are those that cross without full contradiction. Acute angles are formed on each side, and such a discordant condition, if not absolutely necessary, should be attacked by transition and elimination (Figs. 60, 61 and 62).

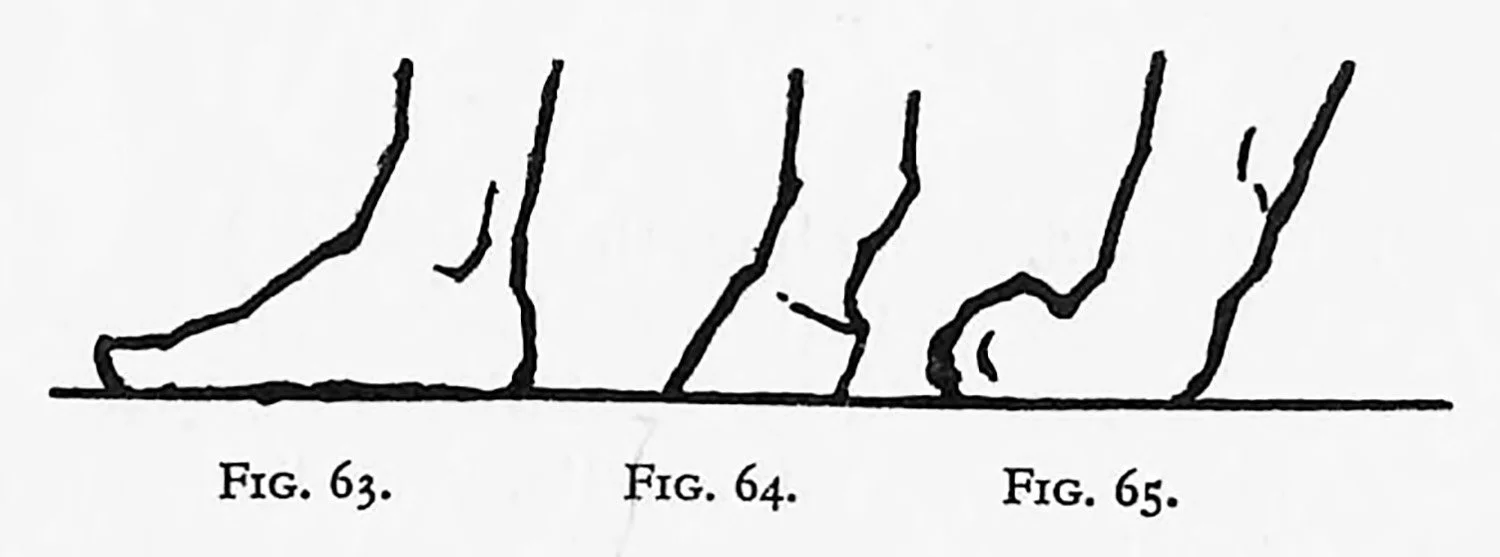

If we examine the human figure, we should notice that the relation of feet to the ground gives splendid opportunities for the study of transition. Such transitions are not quite so obvious as our previous examples, owing to the fact that feet and the ground are separate factors (Figs. 63, 64 and 65). The human figure and other organic forms furnish us with innumerable examples, but enough has been said to show why, when designers create new forms, such a condition of transition is bound to find occasional expression. The capital and base of a column in architecture are expressions of transition, or unifying factors between the vertical and horizontal lines (Figs. 66, 67 and 68). Unrelated planes are unified similarly by transitional planes. The framework and panels of a door ate often related by mouldings—indeed, mouldings are for the most part transitional factors.

Opposing lines without transition give a sense of structure or uncompromising strength, and they can often be left unrelated in a picture. Such a condition gives variety and vitality to the more continuous and reposeful quality of the related lines.

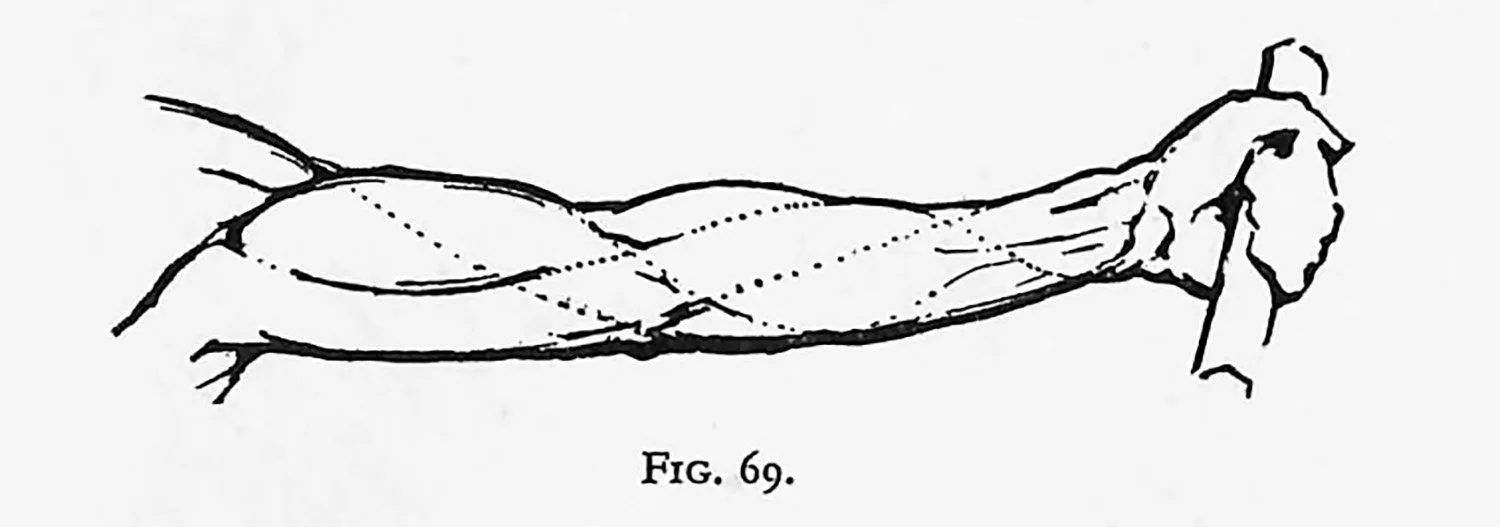

Transition, then, establishes a continuity between lines that are otherwise unrelated, and if we observe the figure once again we shall find that the perception of continuity is one of the great essentials in drawing from the life. We should not only be able to draw a line defining the figure; we must in addition be able to grasp how all the parts interrelate. The trunk, limbs, the head—indeed, the whole figure—seem full of such continuity.

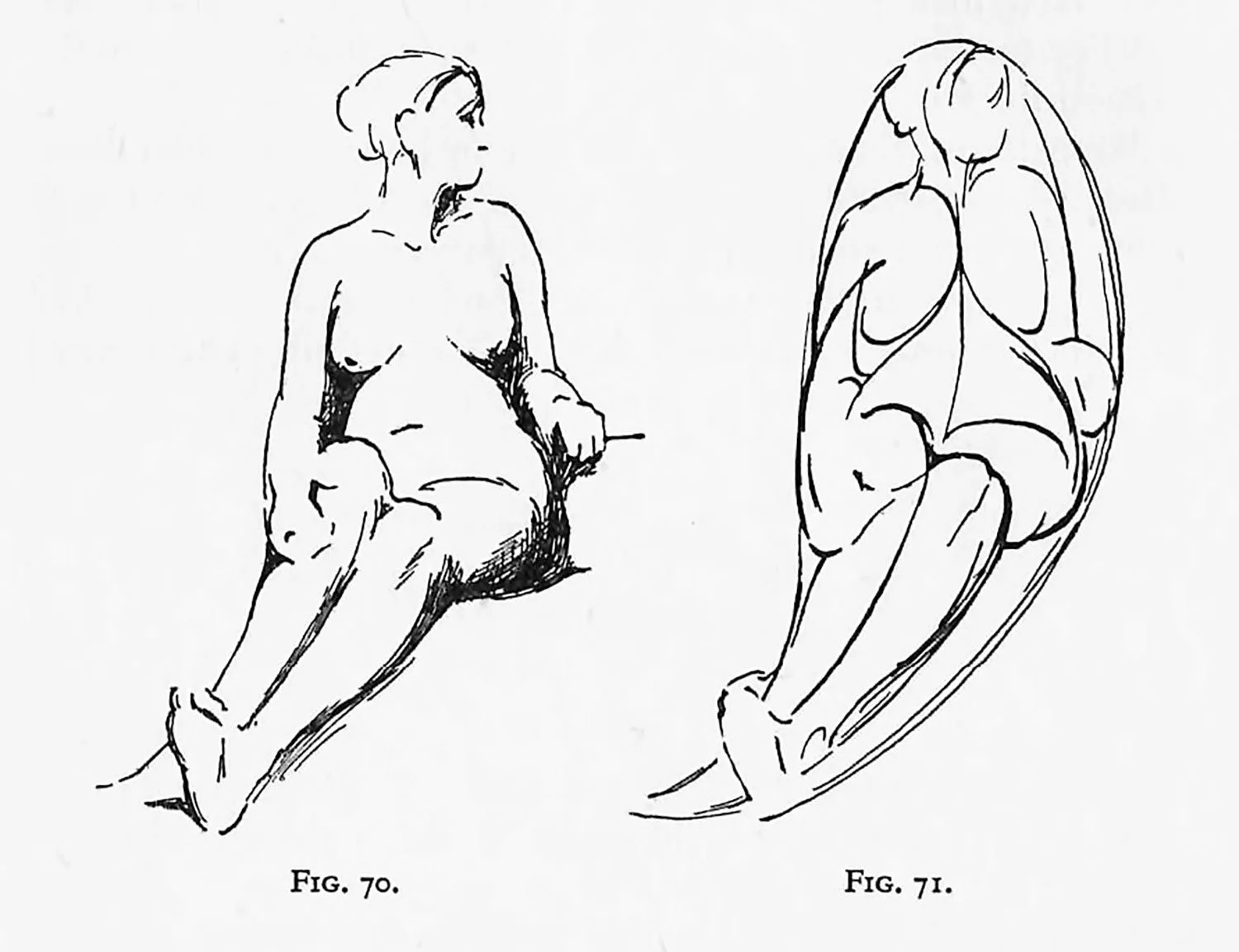

It should be noticed in the illustration given how such lines, after intervals, carry on a similar direction. Sometimes we can actually see such cross-transitions; at other times we must rely upon our eyes to see across the gaps. Life-drawing, apart from proportion and execution, seems to demand this capacity to preserve continuity in order to secure organic unity (see Figs. 69, 70 and 71).

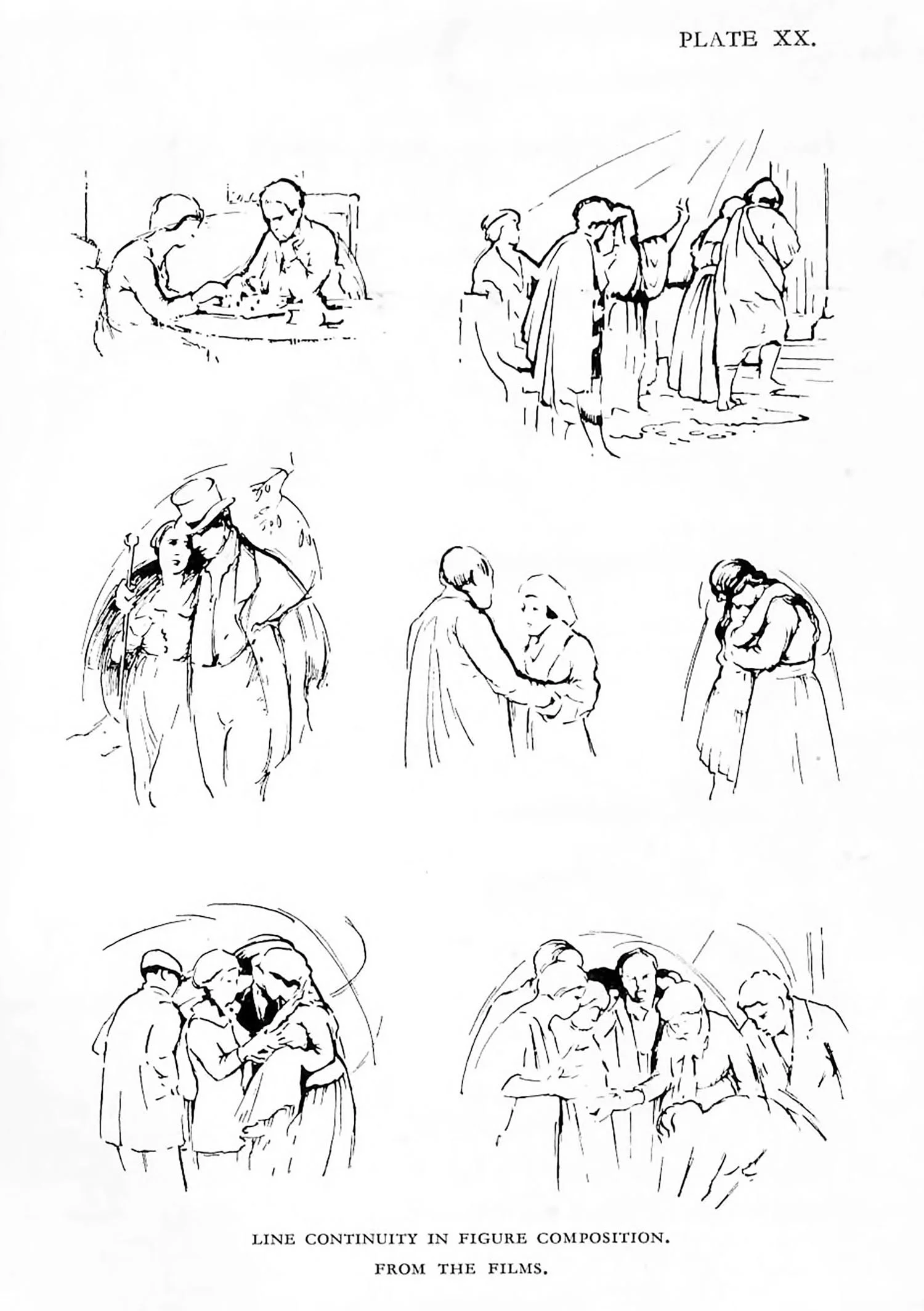

This sense of continuity forms part of the very essence of composition, both in figure and landscape designs. If two, three, or more figures are to form a composition we must treat such groups in precisely the same manner as if we were drawing on a figure. The group becomes a new entity, and continuity of line must be our means of relating the factors in this new creation.

The student who wishes to design figure compositions will find it necessary to study the figure in a special manner. A mere copying of what comes to the eye will be of little use. The figure must be analysed, bearing in mind the continuity of line, and when this has been grasped, he must extend such continuity to combine figures in groups, and finally the continuity of line must extend to the environment. The outstanding point to remember in regard to the environment is that its forms must help the composition: there must be no confusion of intention. The surrounding conditions can give an element of repose, relief, or stability, while the figures are required to have a sttong directional bias, or again the environment may be used to stimulate or enhance the general impulse of the figures. In either case it will be possible to secure an agreement between the lines of the figures and the surrounding forms.

Exercises should be devised for the purpose of studying continuity of line and the other factors that make for success in figure composition. We must endeavour to persuade a few friends, or the least self-conscious members of a class, to group themselves as naturally as possible. Three persons will be sufficient for out immediate purpose. Two might be seated at a small table playing chess or cards, eating, or holding an animated conversation, whilst the third person stands near one of the seated persons as an interested spectator. This arrangement is merely a suggestion for an early exercise, one of the thousands of other possible schemes.

It is our business as composers to observe that, as the interest of the three persons becomes more intense, the continuity of lines will be the more complete. As the interest becomes less and the mental binding-links disappear, the lines that relate will become less and opposition lines will take their place. This principle should permeate all our figure-combinations. Individual units should on no account receive special attention or be drawn in a different manner. The most useful method of attacking such a group would be to draw a simple sweeping line that embraces the whole group, then a few lines to decide positions, together with a massing of tone until gradually, with a watchful eye on continuity of form, the scheme takes shape as a whole.

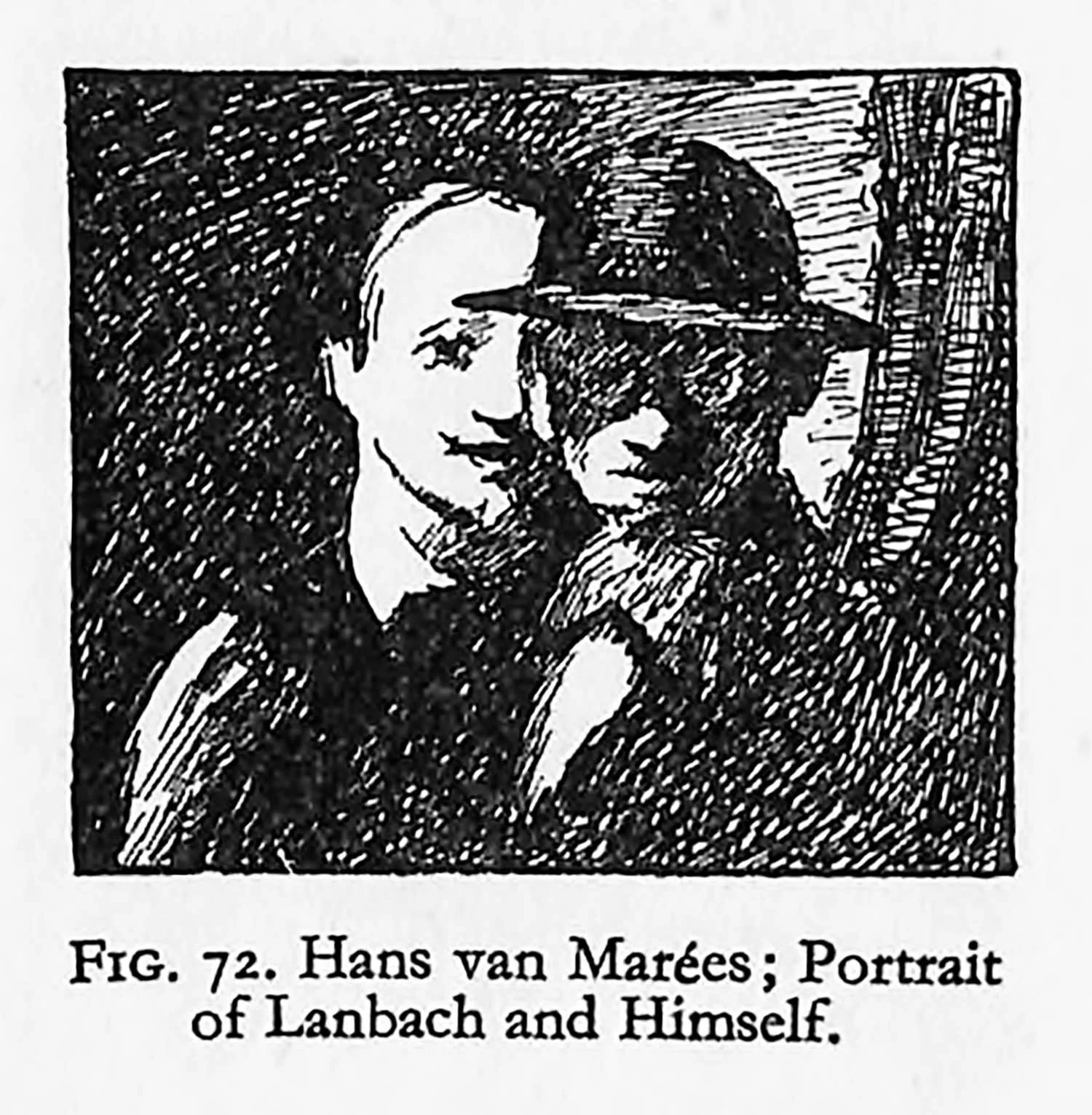

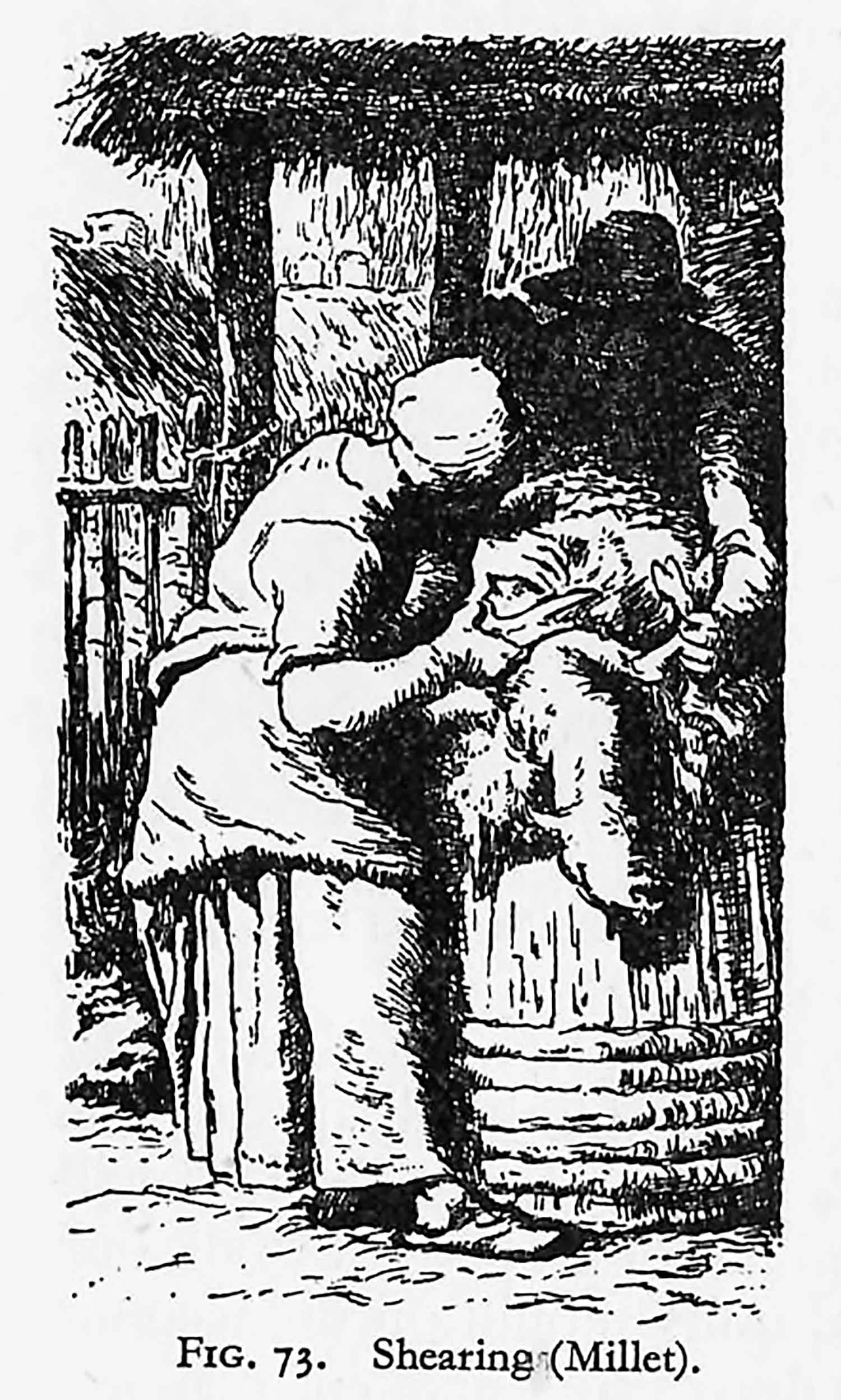

When such exercises have only two figures they are apt to become troublesome because of divided interest. Unity can be achieved by giving one figure the predominance (Fig. 72). The principal person can be arranged to face the spectator, or be given the advantage of position, such as standing on a step, or in the frame of a door, a picture, or an archway. The occupation may provide some arrangement where superiority is suggested, or, again, such a double interest can be unified by a third interest (Fig. 73). In a class of enthusiastic art students, however, it can be safely assumed that sufficient ingenuity will be found present to cope with such troubles (Plates XX and XXII).

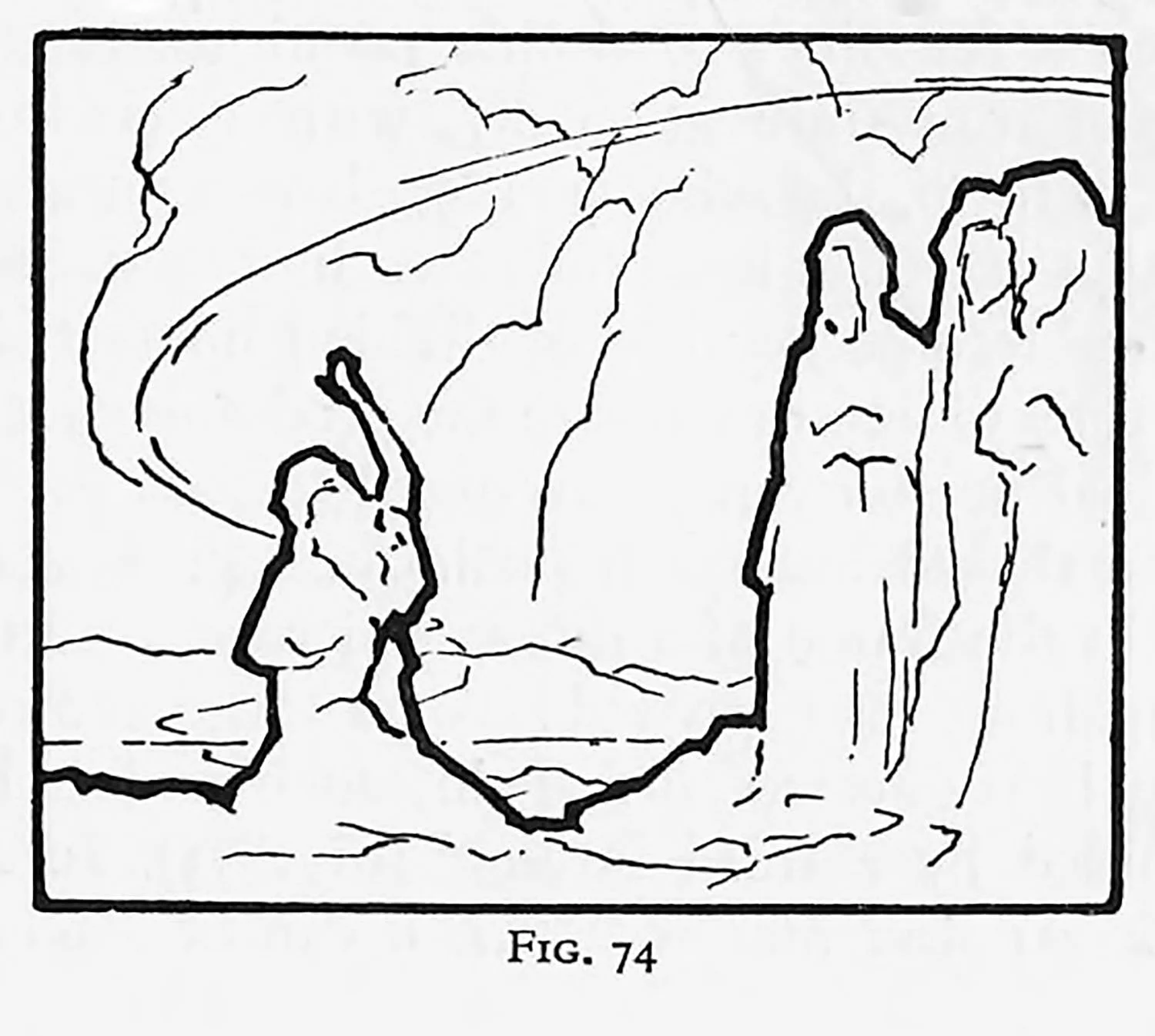

After many efforts the student will begin to realize the value of a dominant contour. By a dominant contour is meant a line that delineates the principal figures and objects and goes across the containing rectangle that limits our picture, and such a contour is given in the accompanying sketch, Fig. 74. If such a contour asserts itself during the struggle for expression, it must be immediately encouraged or developed, for it is one of the most useful factors in a composition. Its value lies in the fact that it keeps the units tied and allows us to develop our aesthetic grasp of the problem, for once a contour or continuous line of a satisfactory character arises we can attempt to make other subsidiary contours live up to it—that is to say, they can interlock with or reiterate it. If the main contour includes a part of the environment still greater progress can be made. When a person who is un acquainted with the technique of composition is asked to illustrate any subject—for example, a nursery thyme—he usually proceeds to draw the individual units, such as Mother Hubbard, the dog, and perhaps finally the cupboard, as separate conceptions.

The moment we can tise to the execution of an all-embracing contour, such as might happen if, with scissors and black paper, we could cut a silhouette of such an incident, we are beginning to compose.

Although line and form possibilities must on occasion be discussed in an abstract manner with such terms as direction, radiation, and continuity, it must never be forgotten that actual ideas are strong, fully developed, and already containing these incidental qualities.

Ideas do not come as a straight line near a curve or as lines that oppose, with here and there a transition, but as a complete entity from an image world, somewhat vague in parts, perhaps, but nevertheless complex.

The student should attack the problem of esthetic expression by rapidly recording such ideas with all their complexities before they fade. Such efforts may be inadequate to reflect the ideas, yet it is only when something of this sort has been attempted that our composition technique can be of any value. The student may help to increase his emotional range by visiting theatres or cinemas for purposes of study, in addition to the organized subjects of class-work, but it is obvious that over and beyond such aids the perception of life itself must come. The commonest event of everyday life is full of esthetic significance to the observant student.

Mere harmony of lines or violence of pattern will be unavailing if our perception of inherent life is lacking.