Chapter IX.

Line-Direction

PERHAPS the best introduction to form-relation is the study of the static and the dynamic. Stillness and movement and the forms that suggest such states must be understood in some degree. We could conveniently call such study line-bias, line-direction, or general tendency of line.

Every student of the fine arts knows that horizontal and vertical lines suggest the static, the stationary—give stillness, quietness and peace, whereas lines of a diagonal character give a general impression of movement. Walter Crane and a number of other writers have laid emphasis on these facts. The student’s own experience in the imitative and memory drawing of objects, both still and moving, must have brought this truth to his understanding. Such ideas may be considered as an introduction to composition, although they requite expansion and additional analysis.

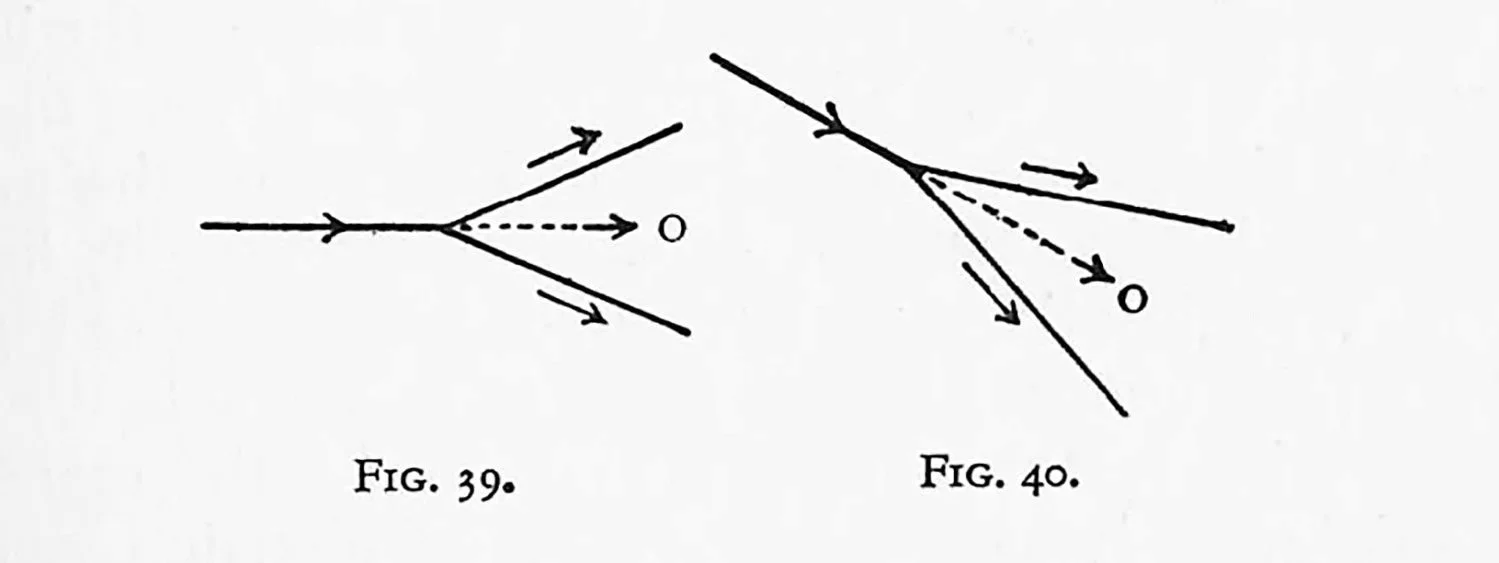

In Figs. 39 and 40, if equal forces are acting—“pulling”—in the direction shown by the outer arrows, the resulting direction of the combined forces will be O. O is the average direction (and when we speak of direction of line in pictorial composition it is the average that we have to deal. with). A pyramid or a gable, in spite of its diagonal lines, is, in consequence, a static form, and does not give a feeling of movement.

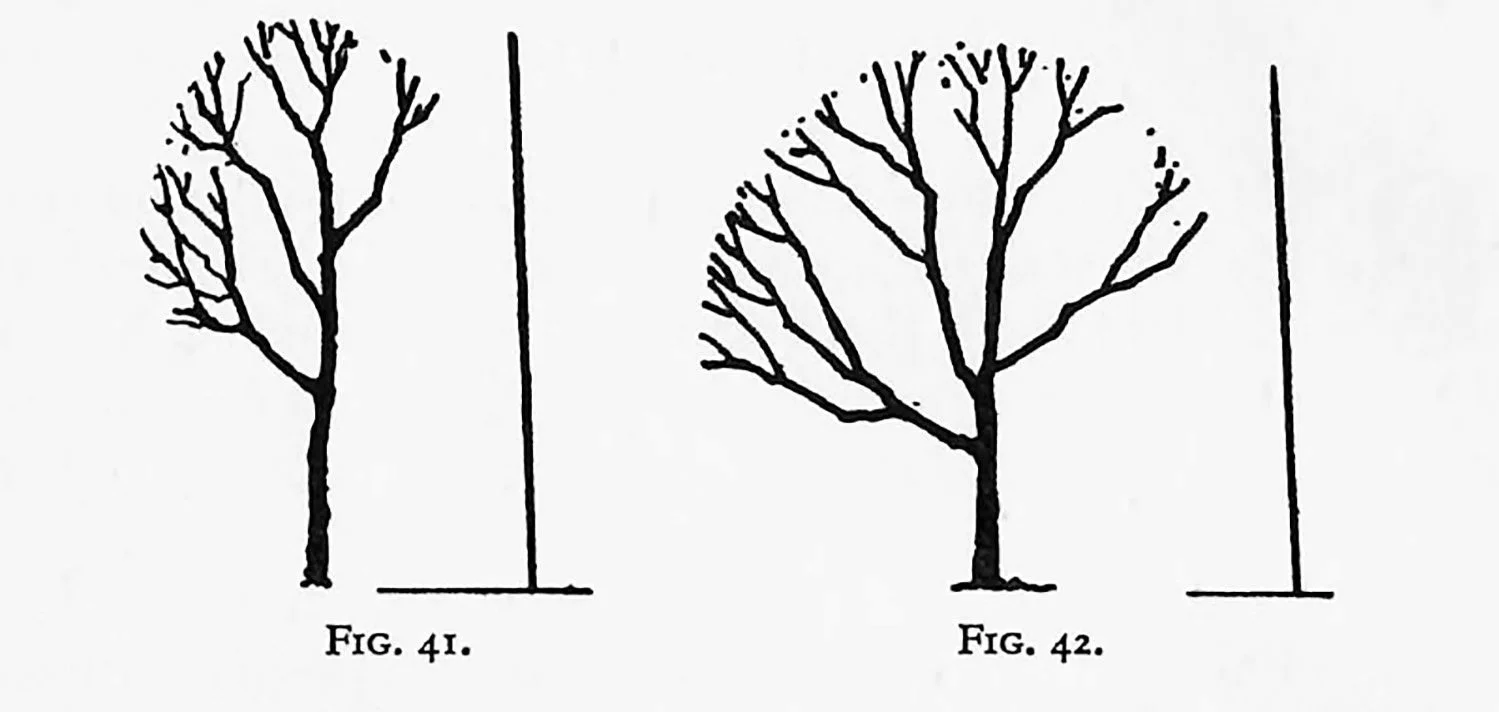

Again, it is important that the student should be able to discriminate between Figs. 41 and 42, for it may seem at first sight that Fig. 41 is more static than Fig. 42. It is not the greater movement in Fig. 42 or the greater average obliquity, but the variety of direction in line of Fig. 42 as against the more monotonous symmetry of Fig. 41.

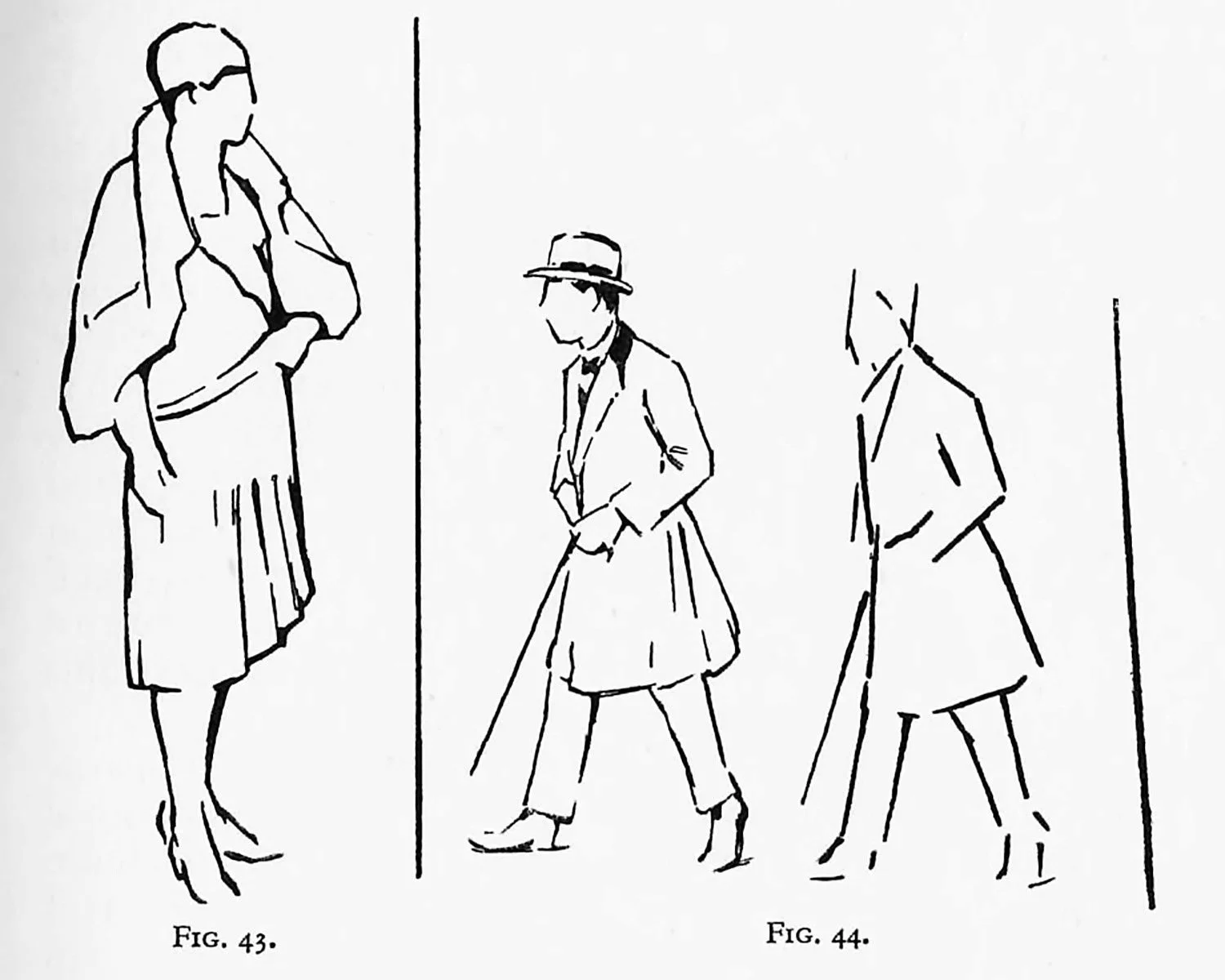

When the human figure is taken as an example the same law prevails. In the standing figure shown the monotony of uprightness is modified by variety of direction given to the different parts, yet the average is vertical.

In such examples as Figs. 43 and 44 the walking figure must not have the average of the vertical example or the drawing will not suggest movement. Such a drawing must accentuate the diagonals in the required direction, and the lines that might counteract must be quietened.

If 45° is taken as the maximum in such an exercise, it will sometimes help to estimate the movement. If the lines from vetticality to 45° be used, with a bias of direction, then we suggest movement. The angles from 45° to horizontality, with a bias, suggest for the most part the stealthy, creeping movements. It must be understood that these remarks are only of a generalized character. Volumes attempting to explain and photograph such movements have been published. Works of this character should be studied in addition to drawing from the actual objects.

It is an excellent, and at the same time amusing, exercise for a number of students to try to draw a running figure. The winning example—the figure conveying the sense of greatest speed—is usually worthy of study in connection with directional lines. If we extend our inquiry a little farther and consider two or more figures are engaged in some common activity, such as digging, swimming, and so forth, we shall find that reiteration of movement gives emphasis; it does not increase the actual movement. The boat-race is an example of emphasis of movement, but the number of oarsmen does not give a greater average movement. When two people are opposed to each other, as in wrestling or boxing, we find the visual movement (that is, the impulse) greatest when one of them gains the ascendancy, temporary or otherwise.

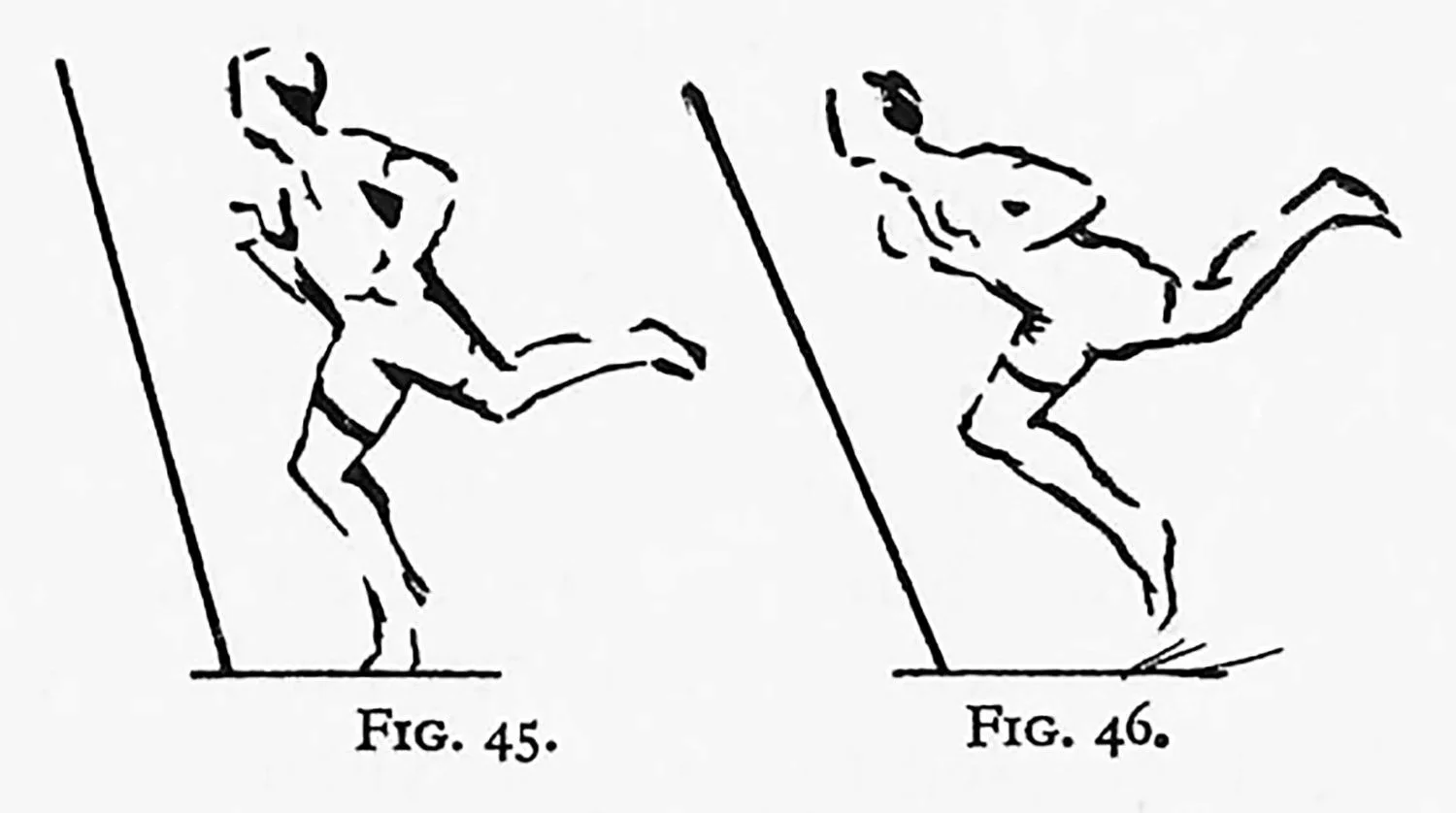

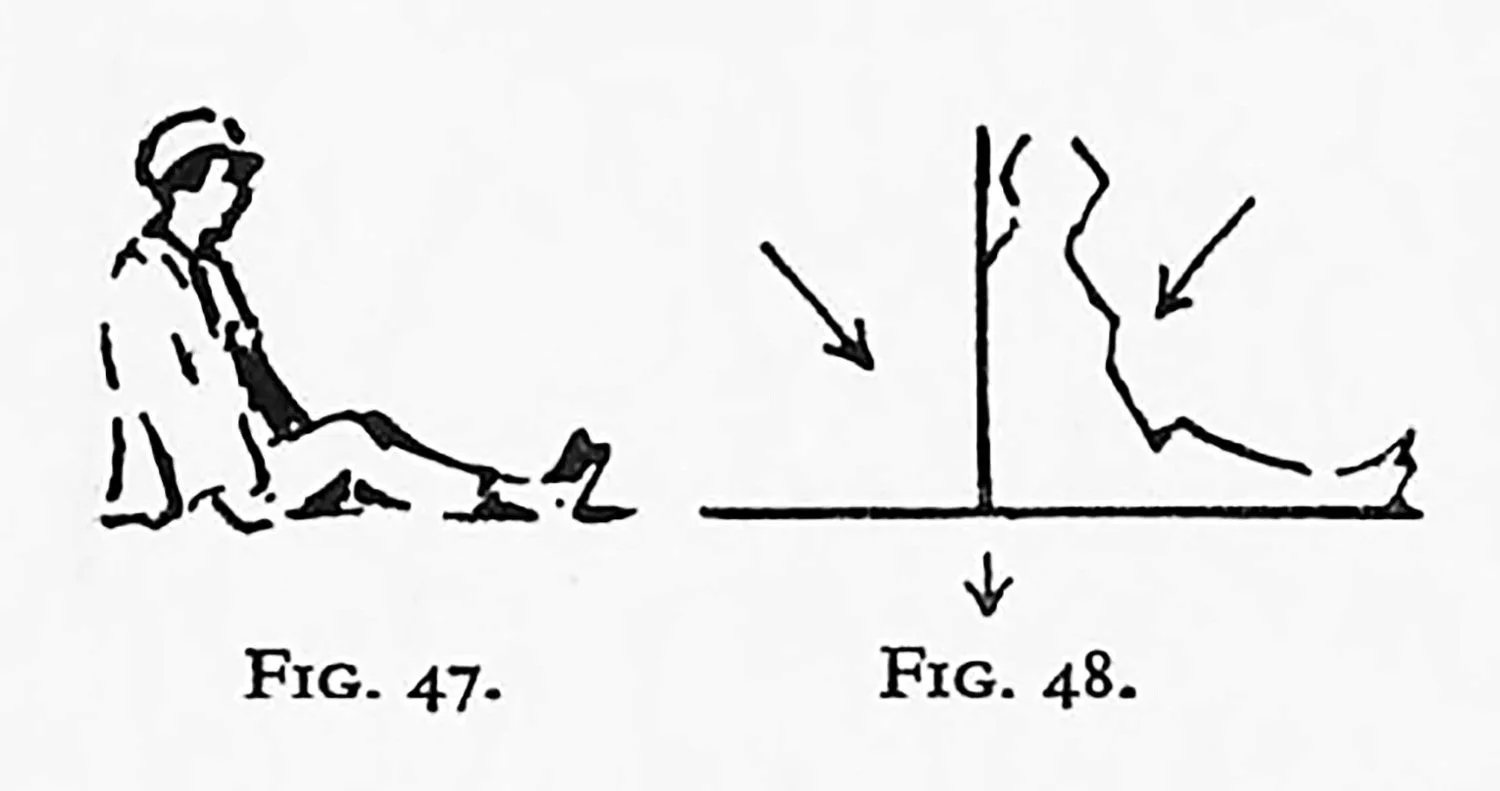

Before an analysis is made of Figs. 45 and 46, it will be clear that Fig. 46 expresses more movement. In Fig. 45 the main tendencies of line cancel out to some extent, but in Fig. 46 the average gives quite a definite slope. The horizontal line of the ground must always be considered as continuous, in which case it cancels out. If this is not understood the student may one day be confronted with a figure as shown in Fig. 47 and asked why the maximum movement has not been attained. The second diagram (Fig. 48) explains the difficulty.

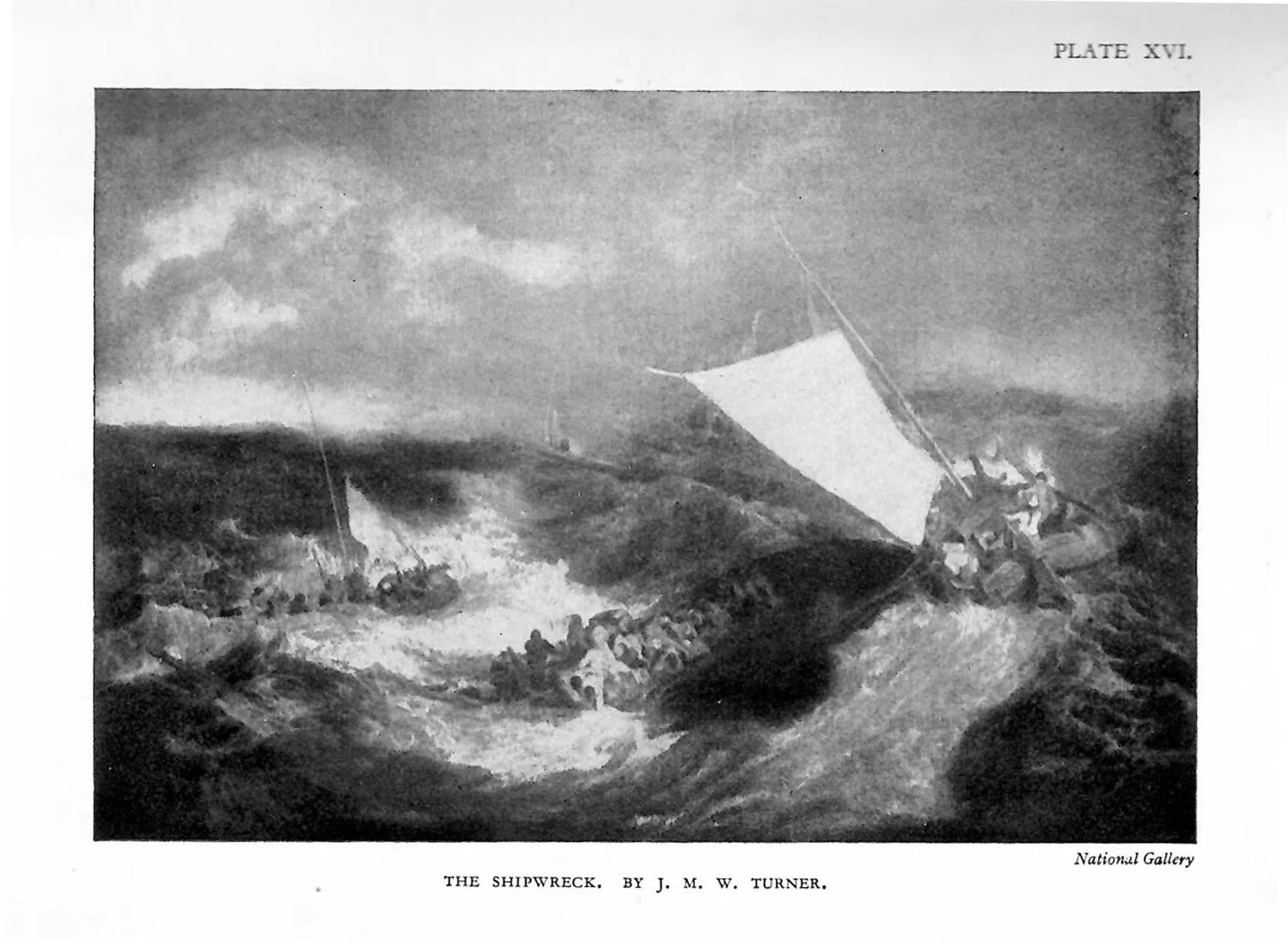

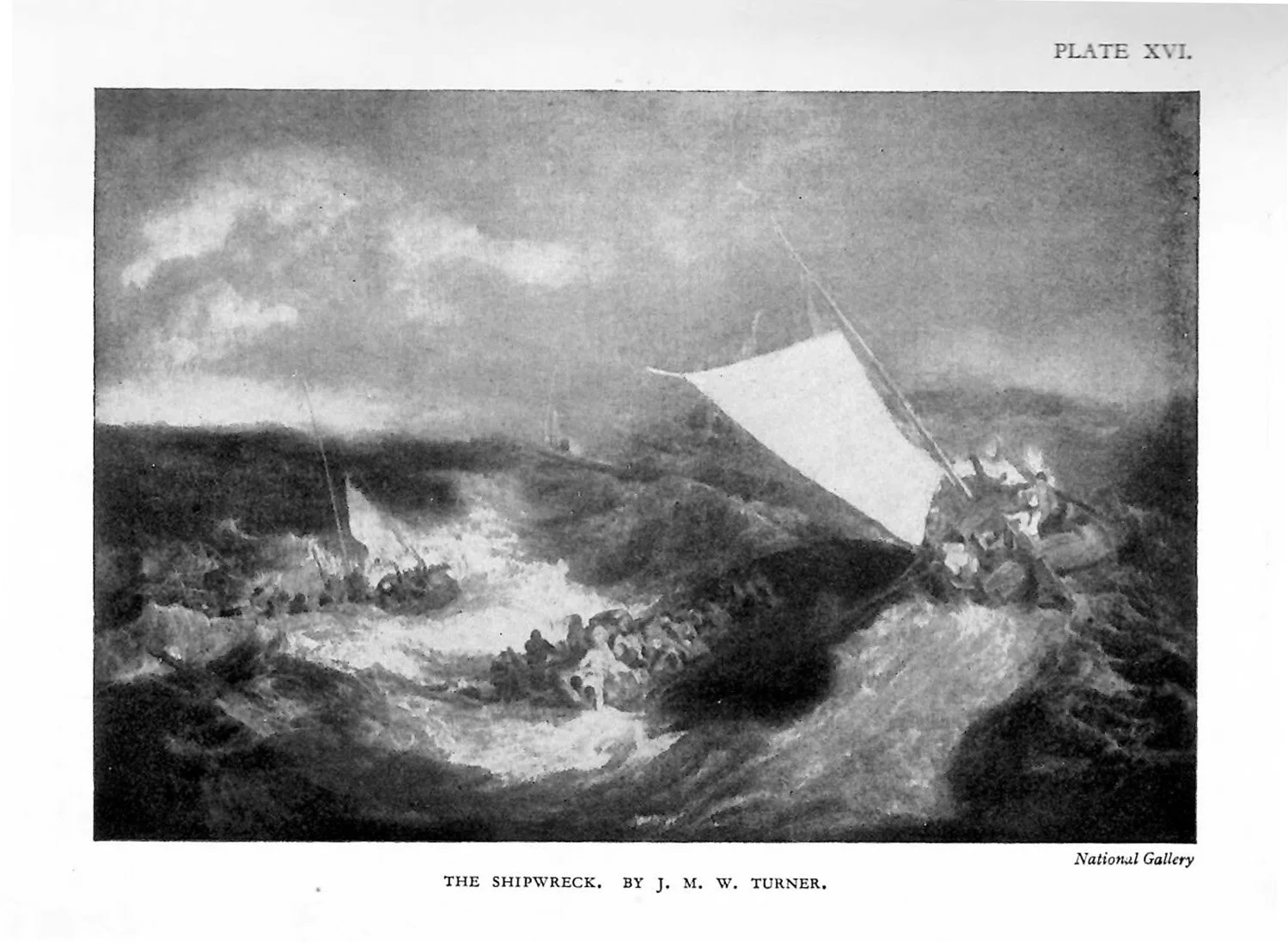

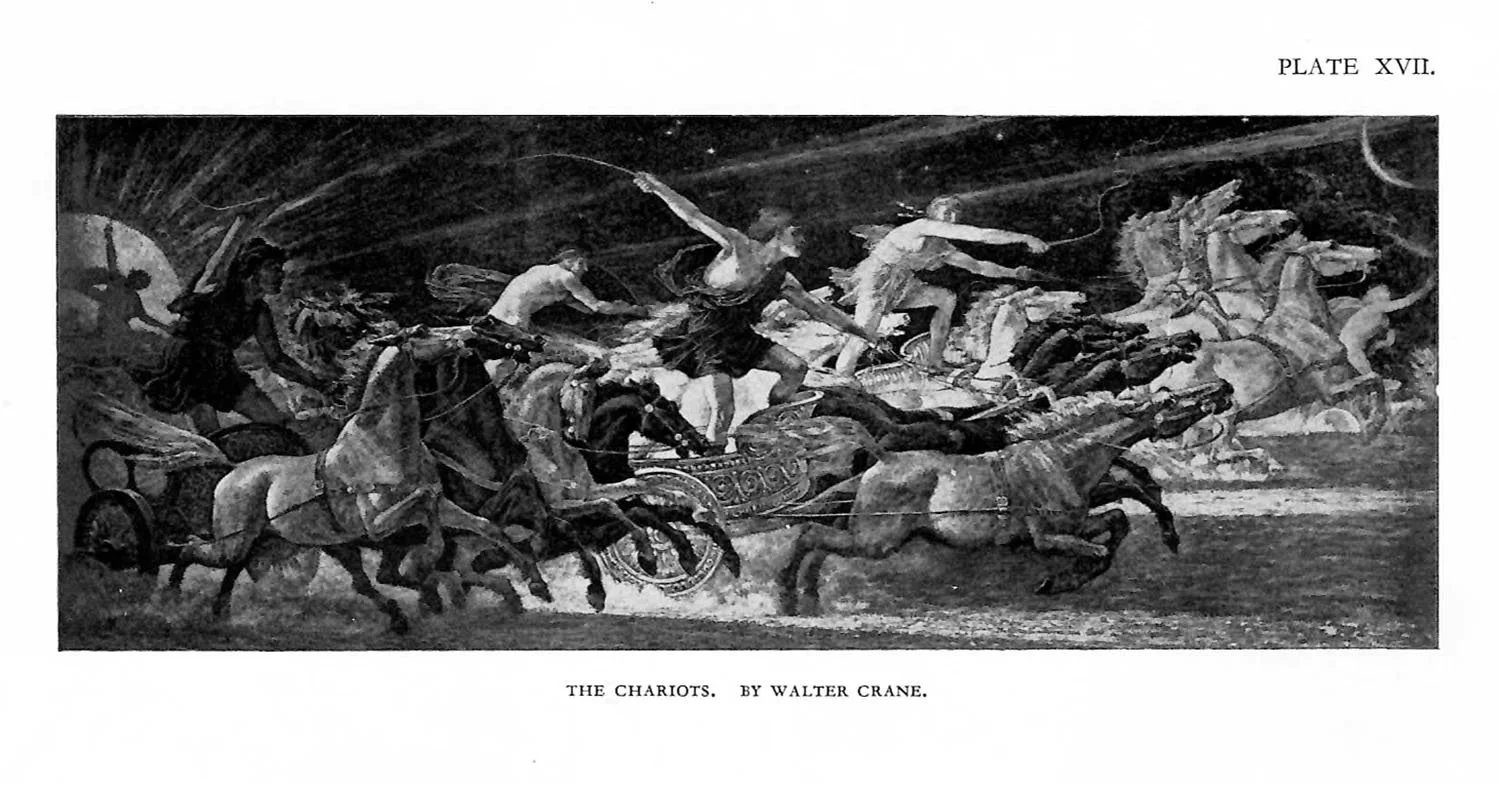

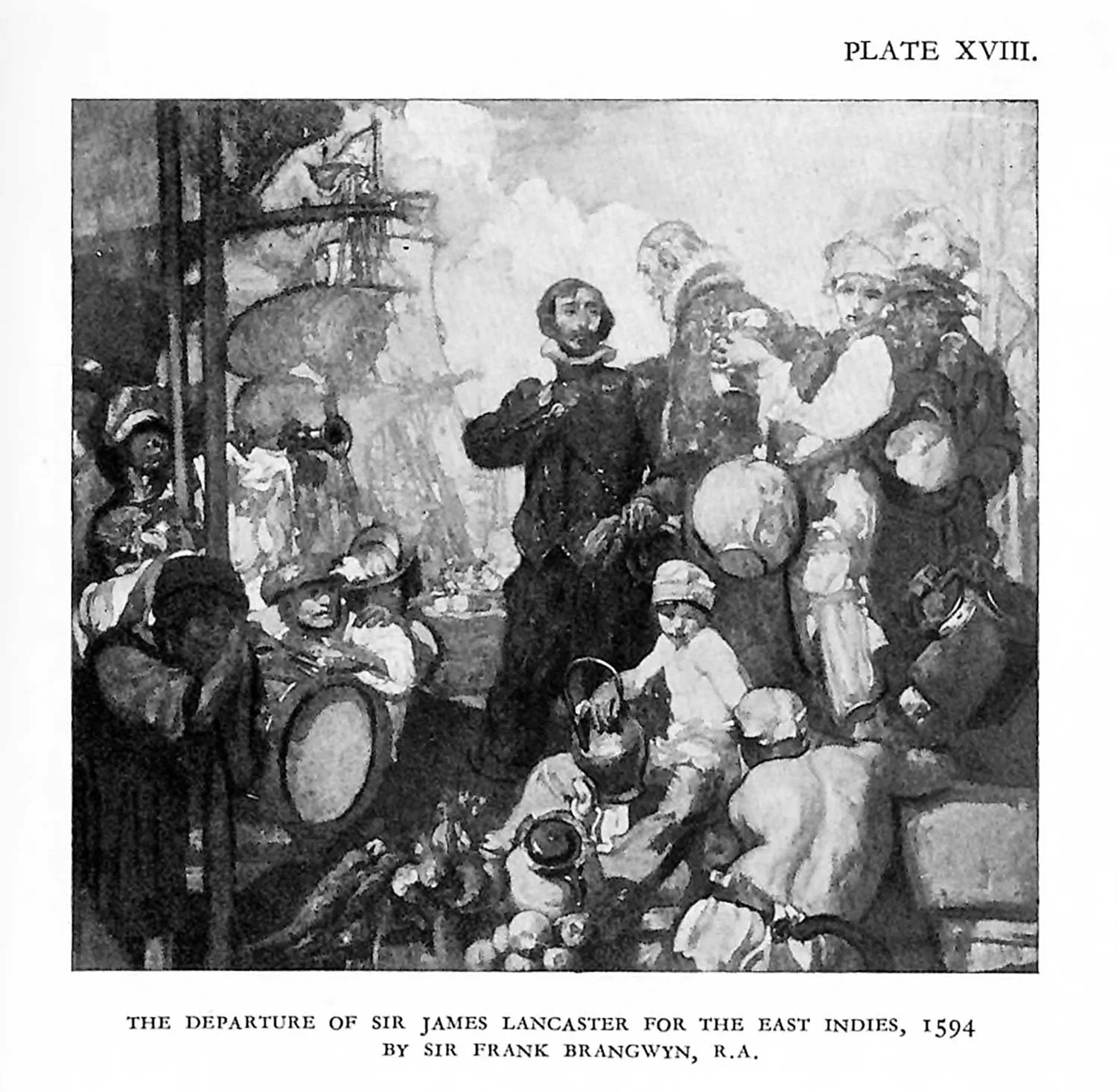

How much activity can or ought to be given to any special motive is a matter of personal inquiry. It often demands considerable ingenuity to minimize or subordinate lines that interfere. Such lines can be kept unobtrusive by quality of tone or lack of accent. Plates 16 [XVI] and 17 [XVII] are worthy of study in this connection.

If vertical or horizontal lines are insisted upon we must expect quietness, stability and repose, but the student must remember that vitality is at stake. If such an arrangement is not redeemed by vitality of tone or of colour, then the result is inclined to be insipid, sleepy, and uninteresting. The stained-glass window can afford to be static in line, for the colour is expected to give the necessary vitality.

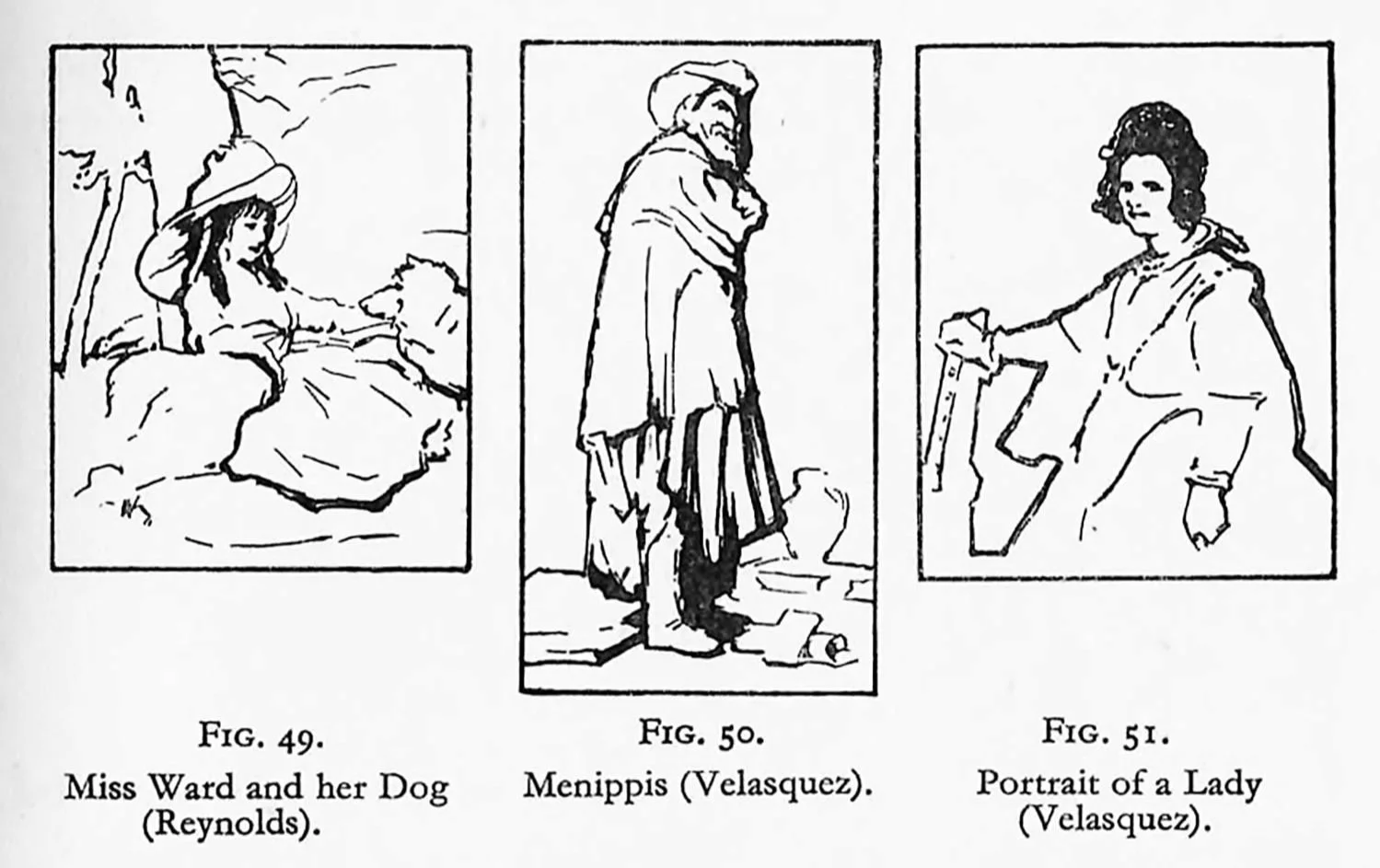

It is always instructive to turn to the masters and examine their procedure; to look at all the available single upright figures ot portraits and observe how variety of line-direction has been used to give this vitality.

In the illustrations, Figs. 49, 50 and 51, we find that although the lines, when analysed, give verticality, yet the variety of line-direction takes away our attention from such a condition and gives vitality. It is at this point that the casual observer is inclined to think that these things were drawn in such a manner “because they were so!” Yes, there is little doubt that the sitters had vitality, but most teachers are aware of the fact that in a life-class, although the model has similar vitality or variety in any so-called static pose, the drawings all have the tendency to become less energetic—ie. more horizontal and vertical—as the work proceeds. It is so with the picture. To start with a few energetic lines is one thing, but it is quite another to complete the work whilst retaining them.

And it is the same with pictures where movement is requited.

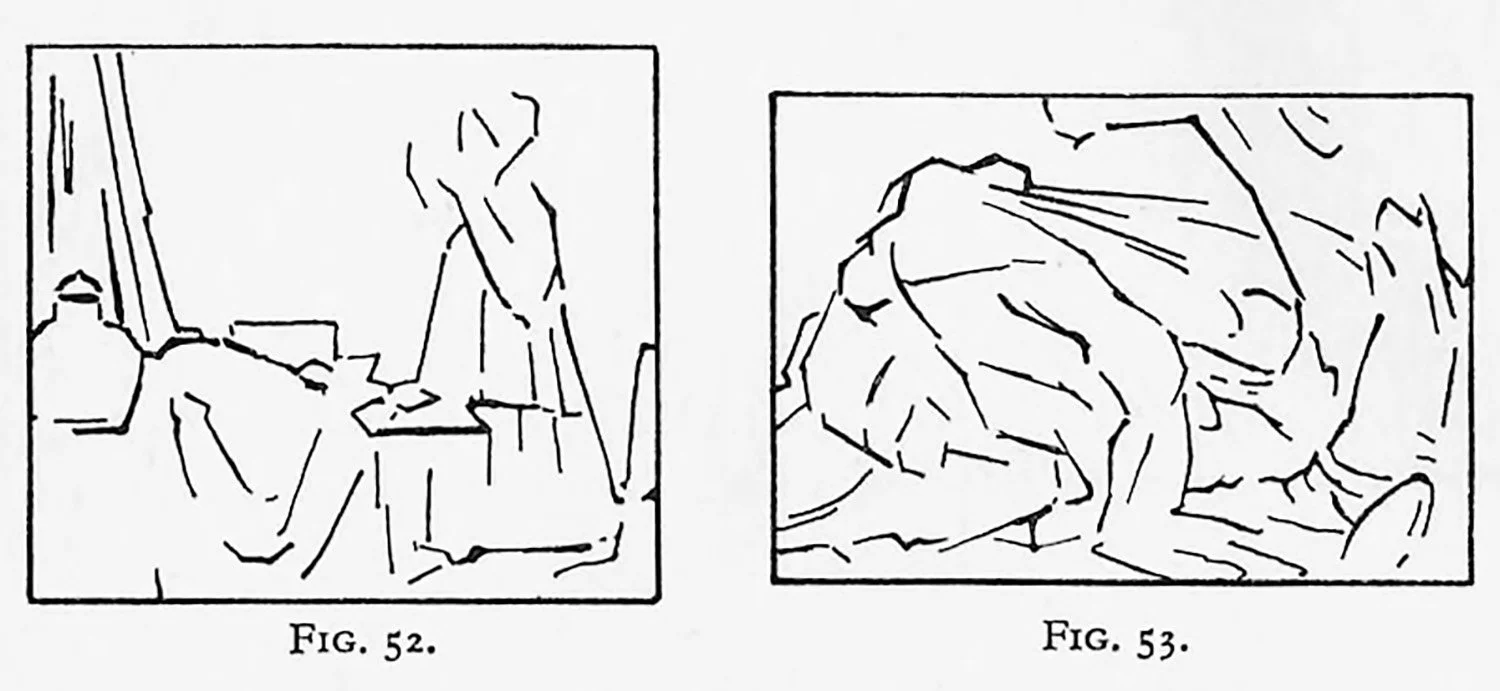

Let us now leave the world of derived forms and consider the lines in the abstract—lines in the condition of Figs. 52 and 53, where subject-matter is not too obvious.

The whole system of lines in a given picture must be considered from the standpoint of tendency or direction of line, quite independently of the representative factor. Unless the student can temporarily detach subject-matter and concentrate on the relation of lines as a whole to the rectangle, he is not composing, but blindly trusting that all will be well. If a still-life group is taken, the separate objects, the background, etc., cease to be separate objects, and the whole as a “newly created entity” in a rectangular shape must be considered, otherwise we do not compose.

Select a few objects that associate themselves comfortably and a background of vertical lines such as cloth or wood panels. Let us suppose that the separate units are as follows:

The background.

The ground.

The bottle.

The cup.

Now place them near together to form a group. If the group has been arranged it must compose as an entity within the rectangle. If composition is to be considered, the units must merge into a “new entity.” It might be as well to state that an entity is something to which nothing can be added or from which nothing can be subtracted without mutilation.

Do the resulting spaces feel monotonous? Ate the objects arranged in such a way so that the lines give the maximum of vitality? Can the same objects be made to appear more full of vitality by altering the view-point?

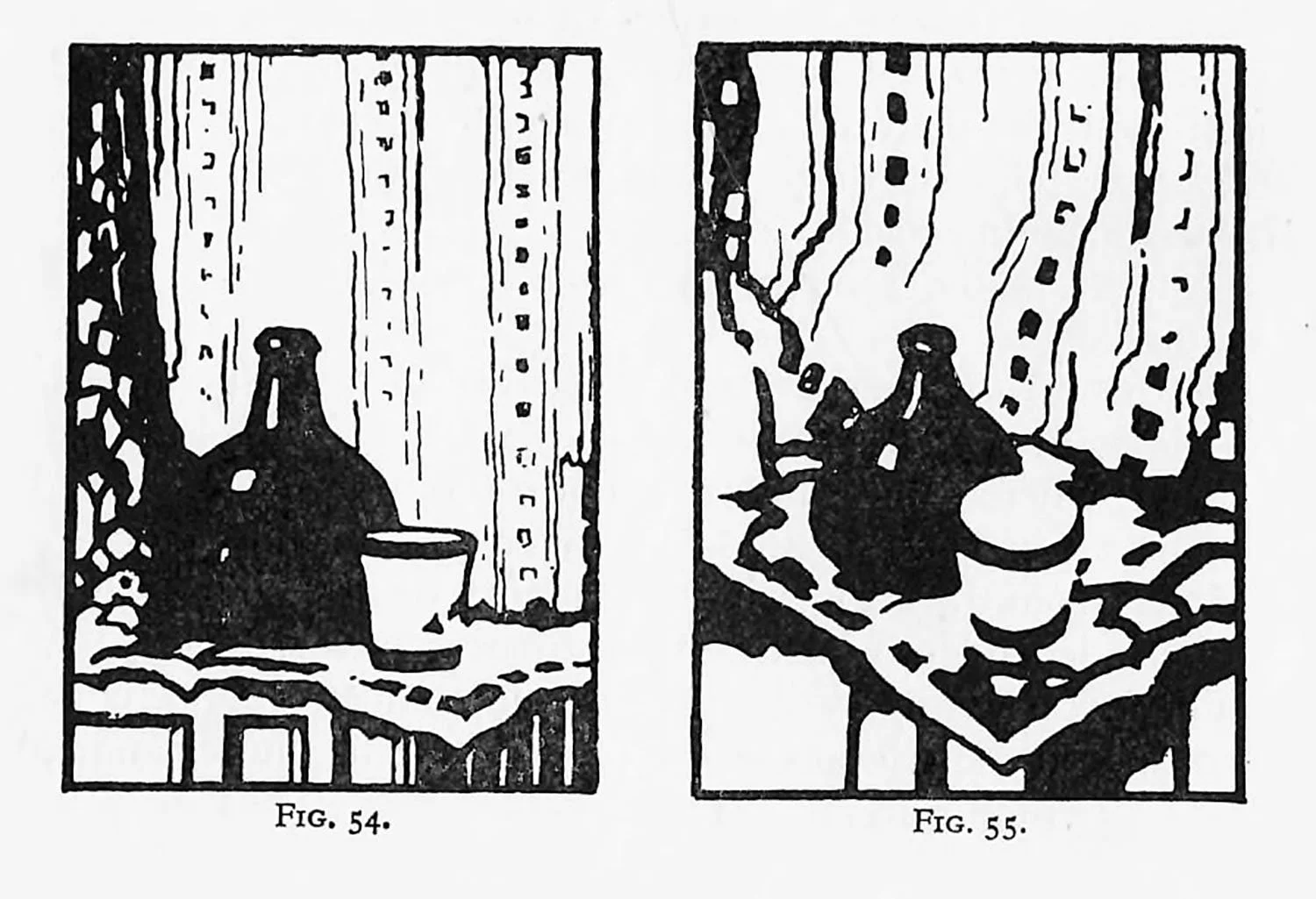

Fig. 54 shows a static rendering, while Fig. 55 shows a more dynamic rendering.

Composition demands that direction of line, whether static or dynamic, should be considered independently of the separate units depicted in a given design.

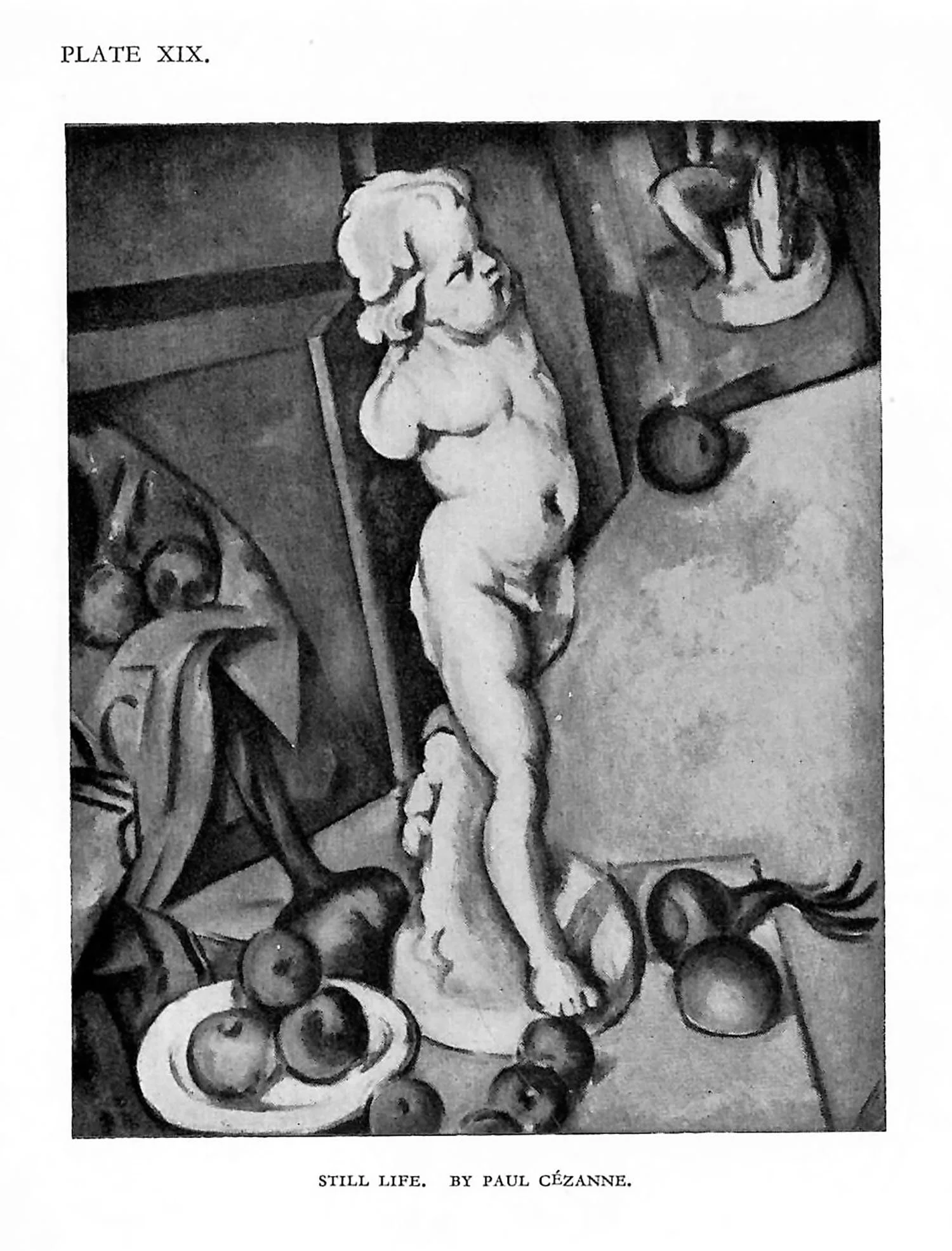

Many of the modern painters are using the view-point of Fig. 55 largely because the direction of line is more “lively.” Modern ctiticism has characterized the art of Cézanne (Plate XIX) and some of the more recent painters as “full of movement.” If we regard lines as being to some extent independent of the units to be expressed, it can be said that static objects have, when painted, and consequently recreated, aesthetic “movement.”