Chapter XIX.

Discords

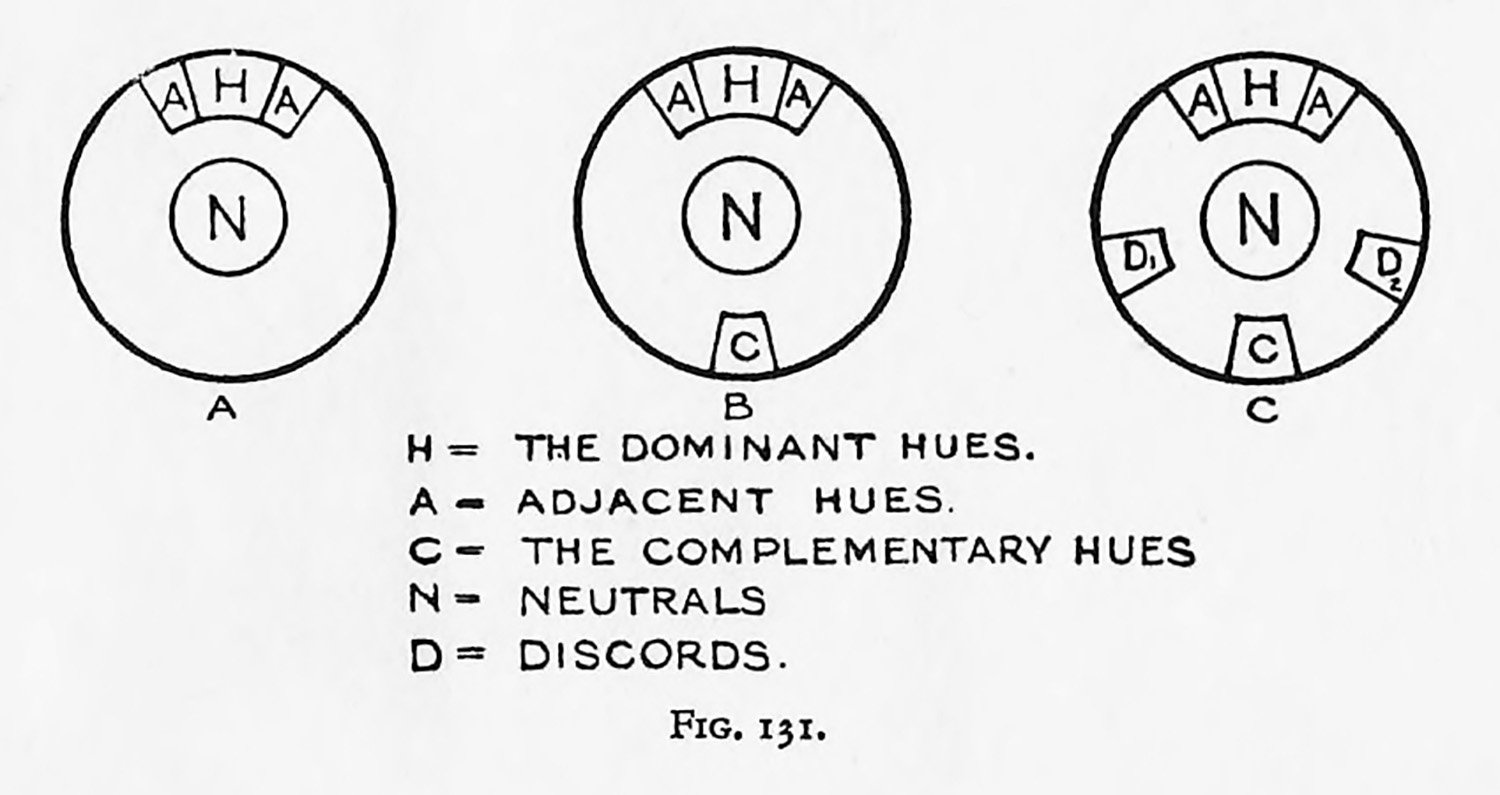

IN this chapter the term “discord” means hues that are not adjacent, or are opposed, to another given hue. If two such separated hues—say orange and purple-red—are seen side by side they disagree, or give a feeling of uneasiness. Such differences of hue do not unite or give relief, for they are neither neighbours nor opponents. Yet when such strangers enter into a colour-scheme they stimulate and challenge our colour-sense activities. If we consult the ring of hues we find that every hue has its discords, removed to a distance on either side. When the distance from the original hue is too great the discords are inclined to fuse with the opposing or contrasting hue, and again, if it is not great enough, they are inclined to unite.

The position that is most effective is where neither of these failings occurs. It is their aloofness, their incongruity as hues, that constitutes the stimulant. Discords, when properly designed in the matter of form and area, are delightful surprises—odd, strange, and unexpected, but nevertheless entertaining. Many portraits have been painted in which the predominant hue of the flesh-colour is discordant, and some of the finest landscapes owe their colour-charm to the “odd” hues on roofs or the unexpected colour-notes on small figures.

Discords naturally detach themselves, and when such detachment is more than the picture (or the artist) can stand, they require amalgamation, and must be resolved by links of intermediate hues to join them either to the general hue or its opposition. The amount of area that can be devoted to such discordant hues varies considerably with individuals. Whilst one person can beat a very wide-awake colour-scheme, and can genuinely appreciate its soundness of structure, another will sigh for a mote cloying statement. Many students have read how the Pre-Raphaelites were reviled for their departure from the indoor monotonous colour-traditions of their time. Every new outburst of this kind, whether in colour or music, seems, temporarily at least, to shatter the world of previous conviction. It is the business of the student to understand such colour-relations in order to be able to loose or leash them as he desires. One outstanding factor in controlling such hues is to observe their balance.

A glance at the accompanying diagram, Fig. 131, C, should show what is meant.

Plate XXXII, B, shows the first colour-scheme with two discords, one on each side. It should be obvious that if D1 or D2 be subtracted separately, the scheme is thrown out of balance. It veers round, and the result is most unsatisfactory, for it has lost its intention.

The; discords must be dual in character, with unequal areas and unequal saturations to balance in informal works, such as pictures. Discords must be dual in character, and may have equal ateas and equal saturations in work or design of a formal character.

The same remarks apply to the second colour-scheme, as shown in Fig. 130, B.

Perhaps the most important fact to remember, after the balance idea, is that there is a possibility of enlarging the discord areas so that the original intention changes its character and the entertaining odd notes attempt to become the colour-scheme.