The Art Spirit By Robert Henri

Chapter 7

The Art Spirit

Robert Henri

Chapter 7

The appreciation of art

Get up and walk back

I once met a man

When a drawing

Every movement

You can learn much

The dominant eye

The average idea

Keep your old work

He paints

Many artists learn to draw

In this pose

I am glad to hear

1.

The appreciation of art should not be considered as merely a pleasurable pastime. To apprehend beauty is to work for it. It is a mighty and an entrancing effort, and the enjoyment of a picture is not only in the pleasure it inspires, but in the comprehension of the new order of construction used in its making.

2.

Get up and walk back and judge your drawing. Put the drawing over near the model, or on the wall, return to your place and judge it. Take it out in the next room, or put it alongside something you know is good. If it is a painting put it in a frame on the wall. See how it looks. Judge it. Keep doing these things and you will have as you go along some idea of what you are doing.

3.

I once met a man who told me that I always had an exaggerated idea of things. He said, “Look at me, I am never excited.” I looked at him and he was not exciting. For once I did not overappreciate.

There are painters who paint their lives through without ever having any great excitements. One man said to me, “I lay it in in the morning, then I have luncheon and I take a nap, after which I finish.” Certainly a well regulated way for a quiet gentleman and quite unlike the procedure of an idea-mad enthusiast who works eighteen hours at a stretch.

One of the reasons that exhibitions of pictures do not attract a larger public is that so many pictures placidly done, placidly conceived, do not excite to imagination. The pictures which do not represent an intense interest cannot expect to create an intense interest.

It is often said “The public does not appreciate art!” Perhaps the public is dull, but there is just a possibility that we are also dull, and that if there were more motive, wit, human philosophy, or other evidences of interesting personality in our work the call might be stronger.

A public which likes to hear something worthwhile when you talk would like to understand something worthwhile when it sees pictures.

If they find little more than technical performances, they wander out into the streets where there are faces and gestures which bear evidence of the life we are living, where the buildings are a sign of the effort and aspiration of a people.

It may be that the enthusiast does not exaggerate and that an excited state is only an evidence of the thrill one has in really seeing.

When the motives of artists are profound, when they are at their work as a result of deep consideration, when they believe in the importance of what they are doing, their work creates a stir in the world.

The stir may not be one of thanks or compliment to the artist. It may be that it will rouse two kinds of men to bitter antagonism, and the artist may be more showered with abuse than praise, just as Darwin was in the start, because he introduced a new idea into the world.

The complaint that “the public do not come to our exhibitions—they are not interested in art!” is heard with a bias to the effect that it is all the public’s fault, and that there could not possibly be anything the matter with art. A thoughtful person may ponder the question and finally ask if the fault is totally on the public’s side.

There are two classes of people in the world: students and non-students. In each class there are elements of the other class so that it is possible to develop or to degenerate and thus effect a passage from one class to the other.

The true character of the student is one of great mental and spiritual activity. He arrives at conclusions and he searches to express his findings. He goes to the market place, to the exhibition place, wherever he can reach the people, to lay before them his new angle on life. He creates a disturbance, wins attention from those who have in them his kind of blood—the student blood. These are stirred into activity. Camps are established. Discussion runs high. There is life in the air.

The non-student element says it is heresy. Let us have “peace!” Put the disturber in jail.

In this, we have two ideas of life, motion and non-motion.

If the art students who enter the schools today believe in the greatness of their profession, if they believe in self-development and courage of vision and expression, and conduct their study accordingly, they will not find the audience wanting when they go to the market place with expressions of their ideas.

They will find a crowd there ready to tear them to pieces; to praise them and to ridicule them.

Julian’s Academy, as I knew it, was a great cabaret with singing and huge practical jokes, and as such, was a wonder. It was a factory, too, where thousands of drawings of human surfaces were turned out.

It is true, too, that among the great numbers of students there were those who searched each other out and formed little groups which met independently of the school, and with art as the central interest talked, and developed ideas about everything under the sun. But these small groups of true students were exceptional.

An art school should be a boiling, seething place. And such it would be if the students had a fair idea of the breadth of knowledge and the general personal development necessary to the man who is to carry his news to the market place.

When a thing is put down in such permanent mediums as paint or stone it should be a thing well worthy of record. It must be the work of one who has looked at all things, has interested himself in all life.

Art has relations to science, religions and philosophies. The artist must be a student.

The value of a school should be in the meeting of students. The art school should be the life-centre of a city. Ideas should radiate from it.

I can see such a school as a vital power; stimulating without and within. Everyone would know of its existence, would feel its hand in all affairs.

I can hear the song, the humor, of such a school, putting its vitality into play at moments of play, and having its say in every serious matter of life.

Such a school can only develop through the will of the students. Some such thing happened in Greece. It only lasted for a short time, but long enough to stock the world with beauty and knowledge which is fresh to this day.

Schools have transformed men and men have transformed schools.

When Wagner came into the world it was very different from when he left it, and he was one of the men who made the changes.

Such people are very disturbing. They often create trouble, we can’t sleep when they are around.

If the art galleries of the future are to be crowded with spectators it will depend wholly on the students.

If there had been no such disturbers as Wagner, auditoriums would not now be filled with listeners.

4.

When a drawing is tiresome it may be because the motive is not worth the effort.

Be willing to paint a picture that does not look like a picture.

The mere copying, without understanding, of external appearances can hardly be called drawing. It is a performance and difficult, but—

5.

Every movement, every evidence of search is worthy of the consideration of the student.

The student must look things squarely in the face, know them for what they are worth to him.

Join no creed, but respect all for the truth that is in them. The battle of human evolution is going on.

There must be investigations in all directions.

Do not be afraid of new prophets or prophets that may be false.

Go in and find out. The future is in your hands.

6.

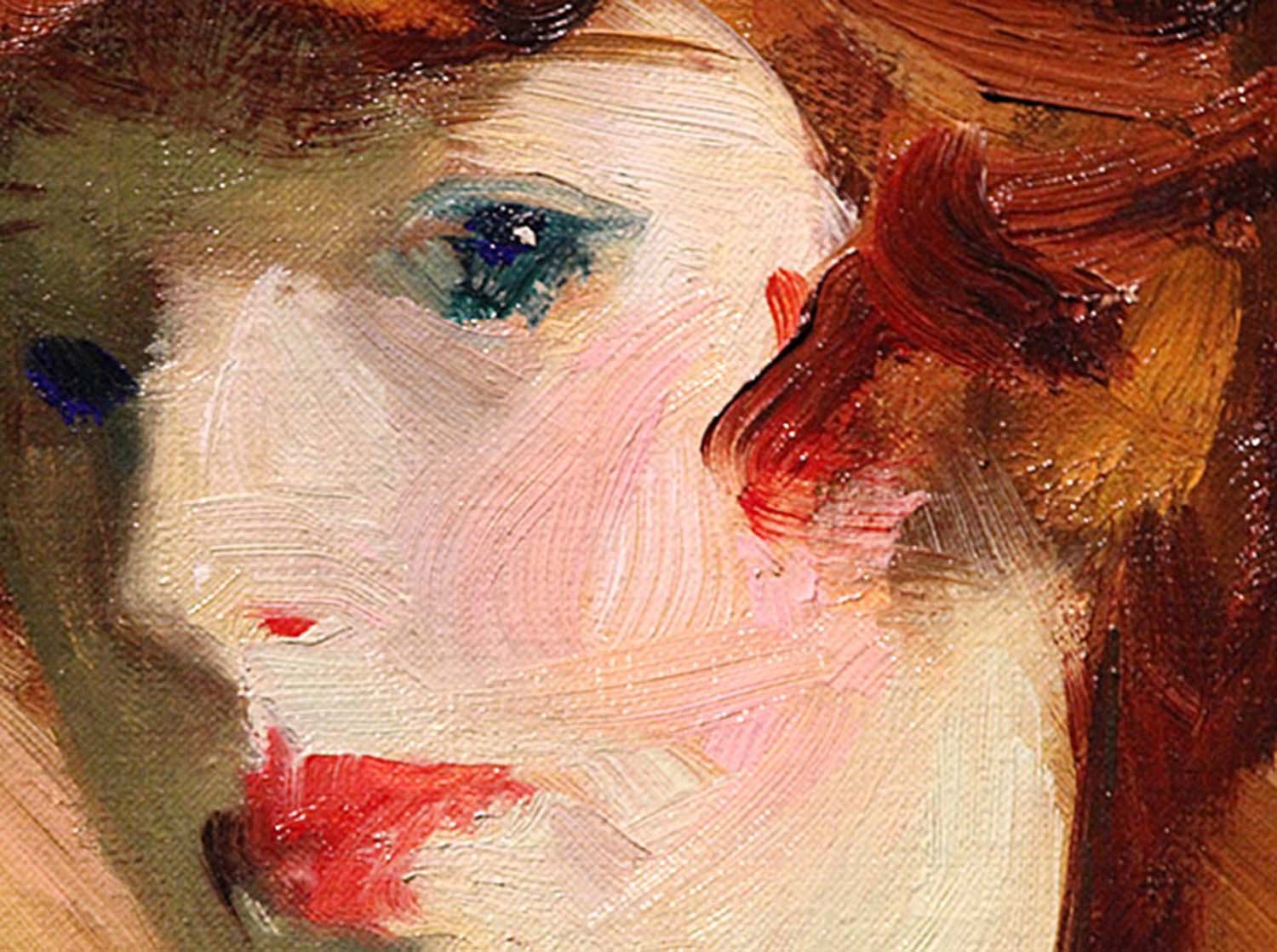

You can learn much by a cool study of the living eye. Examine it closely and record in your mind just what and where its parts are. In pictures eyes should fascinate, arrest, haunt, question, be inscrutable, they should invite into depths. They must be remarkable. You must have your anatomical knowledge so that you can use it without consciously thinking of it, and your technique must be positive and swift. Eyes express human sensitiveness and they must be wonderfully done.

I am sure there are many people—and there are artists— who have never seen a whole head. They look from feature to feature. You can’t draw a head until you see it whole. It’s not easy. Try it. When I first realized this it seemed that I had to stretch my brain in order to get it around a whole head. It seemed that I could go so far, but it was a feat to comprehend the whole. No use trying to draw a thing until you have got all around it. It is only then that you comprehend a unity of which the parts can be treated as parts.

7.

The dominant eye. Note that there is a compositional relation between the eyes—that is, one eye commands the greater interest. If you paint them equal, no matter what the position of the head, the observer will get no right conception of them. In life one eye always dominates the observer. In painting this domination must persist.

8.

The average idea of portraiture needs reconstruction.

When Rodin made his Balzac he made a great portrait. It is probably not so much what Balzac looked like to the ordinary eye; but it is the man as Rodin understood him, and I think Rodin had unusual understanding.

Auguste Rodin

9.

Keep your old work. You did it. There are virtues and there are faults in it for you to study. You can learn more from yourself than you can from anyone else.

After you have made a drawing from the model don’t simply put it away. You are not half through with it. It’s a thing to study.

If you are working from day to day on a drawing, take it home. Put it where you can see it well.

No one can get anywhere without contemplation. Busy people who do not make contemplation part of their business do not do much for all their effort.

Study the drawing out. When you take it back before the model you will have a state of mind far in advance of the state of the drawing.

If it is a drawing of a pose which is not to be continued, just the same, make your study of it—and redraw it. Use plenty of paper. Seriousness does not mean sticking to one piece of paper or canvas.

10.

He paints like a man going over the top of a hill, singing.

11.

Many artists learn to draw a leg or arm in a certain state of action and use the same no matter how unfitting it may be to the subject in hand.

We see in a picture or decoration labeled “Labor,” a man with the muscles in his arms and legs bulging as though he were accomplishing some mighty feat of strength, although the use of all this terrific muscular action may be no more than the carrying home of his dinner pail.

In drawing a man pulling on a rope, make your drawing state fully what muscles are affected by this action.

Develop the power of seeing the points of action; your keenness of sight of such muscular activities must be greater than that of the ordinary observer.

In buying a horse, if you are not acquainted with horses, you will fail to recognize the fine points. You will refer to your friend who is a judge of horses and from his expert knowledge, he will be able to tell at once the signs of the horse’s power, fleetness or condition.

The art student must learn to read the state, temperament, action and condition of his subject through the outward signs, and use the same as a means of expressing and making special what is important to him in the subject.

12.

In this pose our model is as much an artist as any of you. He has a distinct idea of the action he wishes to express, and he keeps well to the idea. It is a piece of good acting. If you would but put as much mind, energy and imagination in your drawing as he does in taking and holding to the spirit of his pose, good work would result.

In drawing this outline you forget what the line signifies because your interest is in drawing the line only as a line. You must think more of what created the line in nature; of the movement and the form that created it. The line is nothing in itself.

Look at this drawing by Rembrandt. Your mind is at once engaged by the life of the person represented. The beauty of the lines of the drawing rest in the fact that you do not realize them as lines, but are only conscious of what they state of the living person.

Here are people represented in differing actions, and each one sensed in his nature, you seem to know all about them. It is the individual significance of the persons in the action of the picture that seizes you. You have been let into that life of long ago.

In this other Rembrandt drawing we see people in a tavern. Among them is an imposing client. Note the way the lines force our understanding of his pompous authority. How different each one present carries himself. In the whole composition there is a unity of line and there is a unity of group, time and place, but each personage is an identity in himself. Variety within unity.

We like to look at these drawings because they carry to us just what was running through the mind of Rembrandt. They express states of life as Rembrandt understood them. They are real historical documents, not of governmental climaxes, but of the real, intimate life of people while they un- consciously live their lives.

Ordinary histories estrange us from the past. The works of such as Rembrandt bring us near it.

The personages in the Rembrandt drawings are seen as in the actions of their lives. Our model on the stand before us is equally an individual, and is at this moment doing one of the things which go to make up his or her life. This studio is no less a place where life is going on in its tragedy and comedy than any other.

The model on the stand is a piece of history, and if you know this you will draw more interestingly, because you will see more interestingly.

Life and art cannot be disassociated, nor can any artist, however he may desire it, produce a line of “sheer beauty,” i.e., a line disassociated from human feeling. We are all wrapped up in life, in human feelings; we cannot, and we should not, desire to get away from our feelings.

In fact lines are only beautiful to us when they bear a kinship to us. Different men are moved or left cold by lines according to the difference in their natures. What moves you is beautiful to you. To all men in a general way human lines have significance.

In all great paintings of still-life, flowers, fruit, landscape, you will find the appearance of interweaving human forms, the forms we unconsciously look for. We do but humanize, see ourselves in all we look at.

Because we are saturated with life, because we are human, our strongest motive is life, humanity; and the stronger the motive back of a line the stronger, and therefore the more beautiful, the line will be.

In looking at certain drawings of landscape by Cézanne, I found myself first filled with a delightful sense of intimacy, of warmth and human feeling.

Presently I became conscious that I was looking at a wonderful orchestration of human forms. In the trees, the rocks, the grasses—everywhere, were variations on the human form, fragmentary but interplaying and forming a magnificent symphony.

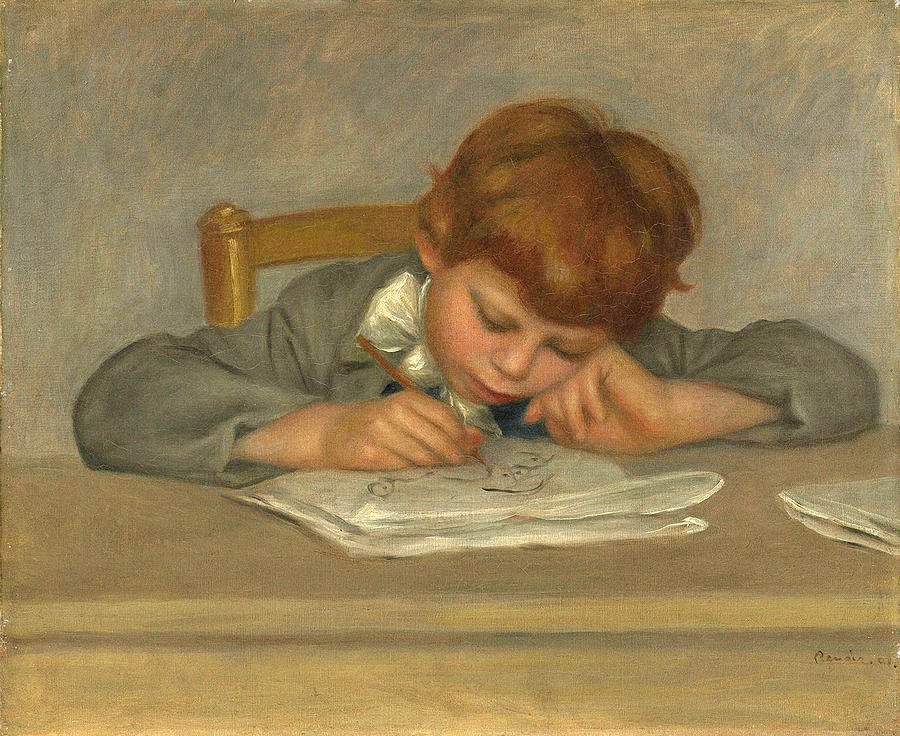

Critics have written that Renoir was not interested in the people he painted, was only interested in color and form, that the who or what of the model was totally negligible to him. Yet one has only to look at those little children he painted, the one bending over his writing, the two girls at the piano, to cite instances; and it will be apparent that Renoir had not only a great interest in human character, in human feeling, but had also a great love for the people he painted.

He needed new inventions in technique, in color and form to express what he felt about life. His feeling was so great that his search was directed, and the result is as we have seen—great rhythms in form and color.

Because a line is beautiful in one picture is no argument that it will be beautiful in another. It is all a matter of relation. The line in a great drawing is not a slave to anatomical arrests and beginnings. There is a line that runs right through the pointing arm and off from the finger tip into space. This is the principal line. This is the line which the artist draws and makes you follow.

It is not necessarily a visible line to the photographic eye.

It is there nevertheless and is hidden in the science of the draftsman. All else that is visible is there only to make you sense this line, and it dominates.

Your eye does not follow the muscle and bone making of the arm. It follows the spirit of life in the arm.

Such a line runs through the whole figure, rising from point to point in measures which are not controlled by the anatomical structure, except in the loosest way. These measures define another dimension—that fascinating fourth if you like—which has to do with your concept of the significance of the whole—that ultra something which has always engaged your interest more than mere facts of the person standing before you.

If you ask me how you are to locate these points on which your line is to rest in its progress, I can only tell you that you most certainly see them and you know them well in your deeper consciousness. It will take some deep sounding to bring them into your intelligence, which is blocked too much now with an eye-seeing vision of material things, things which, however, really do not and never have had much importance to you.

If in your composition of an arm, a figure, a whole canvas, you do come to see these measures and can fix them, you will find the minor forms, the little anatomies, falling wonderfully into their places, easier to do and to regulate as to their importance, than ever before.

The lines which are important in an “outline” drawing are not necessarily those which edge against the background—often the great line moves inward from this and travels across or down the forward body.

In considering lines as a means of drawing, it is well to remember that the line practically does not exist in nature. It is a convention we use.

I think I am safe in saying, until you became an art student, you never saw an outline—you never took the outline into consideration. You saw forms and these forms had character and motion.

If you use lines now as a means of drawing, try to find the way to make them express what you see—forms of definite character and movement. Don’t become a victim of line.

There is a certain kind of penmanship made in schools which seems to draw around the letters of a word like a wire, and there is another penmanship, much more human, that seems to be the word.

In drawing, there are lines which travel fast, which carry the eye over space with a surprising rapidity and land you at a nodal point, where you are forced to rest, and then take new departure at the same or a quite different speed. There are lines that are heavy, dragging, lines that have pain, and lines that laugh.

A canvas may be measured with inches, but the speed with which you travel over it is regulated by the artist.

A line may plunge you into silences, into obscurity, and may bring you out into noise and clarity.

The line around the edge of a figure on a white piece of paper represents the figure’s mergence into the background—its place in air—and represents depths and textures. Some parts of the edge of a body are nearer you, some parts are further away; the outline will show these distances. At places, the bone of the body is near the surface and it is hard. At other places the body is soft. The outline defines these; hardness and softness.

13.

I am glad to hear of your plans and I wish I could be a helper, as you suggest. I understand from your letter that you would like me to write an article.

This brings up, however, the matter that we have several times discussed—whether the cobbler should stick to his last—whether the artist should paint, and put all his energies, his whole heart and mind in what he is best at, both from inclination and experience, instead of lecturing, writing, going to meetings, or going into society. It was only last night that, talking to an artist friend, I regretted there was but one of me, for as I said, if there were two, I could then paint both the people and the landscape. As it is, there being but one of me, I spend six to eight hours a day in actual painting and the rest of the time getting ready for the work, or resting, and in my passage to and from the studio where I paint people, I see most beautiful landscape under rare effects slide by. And this is a true loss to me for I have the feeling, and have had considerable experience, in painting landscape.

I would like to be in many activities. I think that anyone who has had the pleasures of study and work for years may be full of regret because he cannot practice in all the arts.

Painting is a great mystery. No one has ever learned quite how to paint. No one has ever learned quite how to see.

Sometimes we do grip the concert in a human head, and so hold it that in a way we get a record of it into paint, but the vision and expressing of one day will not do for the next.

Today must not be a souvenir of yesterday, and so the struggle is everlasting. Who am I today? What do I see today? How shall I use what I know, and how shall I avoid being victim of what I know? Life is not repetition.

If painting were an accomplishment easy to repeat after “learning,” there would be time and energy for other practices. But good painters (and I consider as good painters all those who work from the will of self-expression) have little time to go afield.

They are generally at work. And as far as sociability is concerned, they are the most social people in the world, at least so I have found them.

I have just laid down a book and the caress of my hand was for the man who wrote it, for the great human sympathy of the man and his revealing gift to me through the book. I have never seen the man, do not know his outside, but I am intimately acquainted with him. His warmth is all about me. Insofar as I am capable I am his kin. I am not anxious to see how well he dances, or how well he paints. He has said what he wanted to say to me in the way he wanted and thought best to say it.

I do not like the very modern fancy which makes an actor of a man as soon as he has proven himself a pugilist.

It is true, no doubt, that if my writer is deflected from writing to dancing or painting, somewhat of his genius will appear in these arts. But why should he be deflected, since it is the man’s self we want, and he has found and developed his best way of giving it.